The following was originally published as an article in the journal “Athonite Dialogues” (Ἀθωνικοί Διάλογοι) on September 15, 1980.

***

Dear brothers!

A few months ago I was in a monastery far from Athens. There was a large group of tourists from Athens there the same day. They were all pious academics, some young and unmarried, and some the heads of families. At trapeza, after the reading, a conversation started up, and one of the pilgrims asked: “What does monasticism offer to a suffering society? Wouldn’t it be better if monastics were among the unmarried clergy or lay preachers, and carried out their missionary work in the world?

The abbot appealed to my humility and asked me to answer the question posed. My word at trapeza, although improvised and delivered without any preparation, in my humble opinion, offers a particular addition to the article, “Orthodox Monasticism and Mission,” recently published in our journal (April-June). I’m sending it to you as is, and if you also think it contains something “better than silence,” you may publish it.

With love in the Lord,

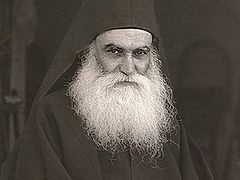

Archimandrite Epiphanios

***

Two Monks. Artist: Alexander Zavarin The clergy who labor in the world carry out an extremely important task, which no one can belittle or despise. They are instruments of grace, ministers of Christ, and stewards of the Mysteries of God (1 Cor. 4:1). They continue the work of the Holy Apostles down through the centuries. They preach Christ Crucified and Risen, they teach repentance and remission of sins “in His name.” By means of this teaching and the celebration of the Holy Mysteries, they lead multitudes of people to the eternal Kingdom of God. “Apart from these, there is no Church,” according to St. Ignatius the God-Bearer of Antioch (To the Trallians 3:1).

Two Monks. Artist: Alexander Zavarin The clergy who labor in the world carry out an extremely important task, which no one can belittle or despise. They are instruments of grace, ministers of Christ, and stewards of the Mysteries of God (1 Cor. 4:1). They continue the work of the Holy Apostles down through the centuries. They preach Christ Crucified and Risen, they teach repentance and remission of sins “in His name.” By means of this teaching and the celebration of the Holy Mysteries, they lead multitudes of people to the eternal Kingdom of God. “Apart from these, there is no Church,” according to St. Ignatius the God-Bearer of Antioch (To the Trallians 3:1).

But if it’s impermissible to denigrate the mission and work of clergy serving in the world (as well as of the zealots and bearers of gifts of grace from among the laity), it’s also impermissible to denigrate the mission and work of monks. The Church is led unerringly by the Holy Spirit.

If monasticism was something superfluous and useless, if it were a state without essence and meaning, it wouldn’t be an institution in the Church, the holy Ecumenical and Local Councils wouldn’t concern themselves with it, and the great and God-bearing Fathers wouldn’t have written about it.

If monasticism weren’t the work of God, if it weren’t the fruit of the Holy Spirit, if it weren’t a plant that the Father has planted (cf. Mt. 15:13), it would have been expelled as a “foreign body” from the body of the Church from its very appearance.

But monasticism sprouted in His field (cf. 1 Cor. 3:9), in the holy Church, and in it was strengthened and bore fruit this field precisely because it was “the plant of God.” Doubt about the dignity of monasticism is unthinkable from an Orthodox point of view. Any attacks on it as an “institution” are pure theomachy.

And I, brothers, belong to the number of the clergy serving in the world. But as an obedient child of the Orthodox Church, I must follow her teaching and not question or even condemn that which it, “led by the Holy Spirit,” has approved and embraced.

Don’t we know that our calendars are full of the names of monastics? Martyrs and monastics (also martyrs “by will”) make up eight, and maybe nine-tenths in the “catalog” of our saints! We’re not more perfect in theology or wiser than the Church. We don’t know better than it what agrees and what disagrees with the spirit of the Gospel. He who rejects monasticism as discordant with the spirit of Christianity becomes a heretic, because he places himself above the authority of the Church.

No one forces anyone to become a monk. If someone has the desire (but also the calling!) to serve the Church in the world, then this is holy work, and the path to him is open, and no one hinders it. But those who have a draw to monasticism shouldn’t be attacked or hindered by us. Holy is their desire and blessed their choice. The Holy Spirit divides gifts to every man severally as He will (1 Cor. 12:11).

I’m not going to reveal the dignity of monasticism as the “most perfect path of deification,” based, of course, not on my own experience, which doesn’t exist, but on the teachings of the Holy Fathers. I’m not going to speak about the difficult and truly heroic podvigs of monks to purify themselves from “shameful passions,” podvigs, the “taste” of which we living in the world barely know. I won’t speak about the unceasing Divine service to God, worshiped in the Trinity, celebrated in the sacred monasteries and in the heart of every monk. I’m not going to talk about the Heavenly gifts with which many monks were adorned.

I will focus on just one point, which is directly relevant to the given question. And I dare say that the monk’s offering to “suffering society” is very great! I dare say that a monk—every monk (of course, a true monk)—is a missionary!

I said “every monk” because I don’t want to limit missionary work only to those monks who, having the grace of the priesthood, go beyond their sacred enclosures, and with permission of the local bishop, go around teaching and confessing in cities and villages; or to those who, endowed with a talent for writing, sometimes of rare strength, publish wonderful books and thereby edify thousands of souls, and for whole generations, as, for example, St. Nikodemos the Athonite.

I am convinced, brothers—and don’t think I’m speaking paradoxically, because I will substantiate this certainty—that those monks who have never left their monastery and never written a single line are also missionaries.

“You mean prayer?” you might say.

Of course I have in mind prayer, but not only prayer. The power of prayer, and especially of the prayers of those who have “a life purified or cleansed for God,”[1] of those “who have acquired much boldness before God,” is all-powerful. One “heartfelt tear” of a holy man can lead to results that would otherwise require many sermons and many books. Prayer works miracles. The effectual fervent prayer of a righteous man availeth much. Elias was a man subject to like passions as we are, and he prayed earnestly that it might not rain: and it rained not on the earth by the space of three years and six months. And he prayed again, and the heaven gave rain, and the earth brought forth her fruit (Jas. 5:16-18).

I’m not addressing non-believers now, or people who are indifferent to faith; I’m talking to believers. So there’s no need for me to expand on this point. We all accept the power of prayer, we all know about its salvific activity. Therefore, everyone should look at the prayers of monks as the greatest offering to the world.

Think about it! There isn’t an hour, or a single moment in the day when fervent prayers aren’t ascending to the throne of the Almighty. All twenty-four hours in a day, God is “besieged” with fiery and tearful petitions to have mercy and save the world. When we’re working, when we’re eating and when we’re sleeping, someone is praying for us, someone is “working out,” watching and calling out in a spiritual podvig: “Lord, have mercy!” Isn’t this offering enough?

I visited one large monastery a few years ago. Among the monastics I knew was one who was almost a hundred years old—illiterate, but a holy soul. She no longer got out of bed due to her age. Weeping, she told me her complaint:

“Ach, that abbess! I ask her to give me work to do here on my bed, since I can’t get up if they don’t hold me up, but she doesn’t give me any. I can twist yarn into skeins. But she doesn’t give me any work. She says I worked eighty years in the monastery” (she joined when she was sixteen). “But that means I eat my bread for nothing. Others work and feed me. What should I do? The abbess is unyielding. I was so worried that I didn’t even want to eat. But then I thought of something and calmed down. I decided to constantly pray for everyone. Thus, it seems to me that I work. You see this prayer rope?” (She showed me a prayer rope with very large knots). “I never let it out of my hands, neither day nor night, except for the two or three hours I sleep. I always pray for the abbess and the nuns who work so that I can eat. And I pray for others: for our Vladyka and for other hierarchs, for priests, for preachers, for bosses, for judges, for the army, for the police, for teachers, for students, for widows, for orphans, for everyone I remember. Thus, I feel less of the weight on my soul that comes from eating without working…”

I cry every time I remember this scene. I never saw this venerable nun after that. A few months later, she departed to the other world, to continue her prayers “from the depths,” “for everyone she remembers” from there (I hope for me too…), although now without her thick prayer rope, which was buried together with her holy body.

But prayer is one of the means—the first—by which a monk carries out missionary work; that is, helping souls be saved. There are two more ways, brothers.

The second way: Where has there ever been a monastery that didn’t become a drawing point for the people? Where has a hermit labored where a cloud of visitors didn’t come to his cave, his mountain, his den of the earth (cf. Heb. 11:38), seeking from him either a “word of comfort,” or at least to behold his face—a sight that teaches many things and edifies much?

And this isn’t just in olden days, but in our day too. How many wanderers through life that labour and are heavy laden (Mt. 11:28) run to the holy monasteries, to find a little silence of soul! How many benefit from the impressive atmosphere that reigns there during the Divine services! How many unbelievers or indifferent people, visiting the sacred abodes of monasticism as tourists, feel a prick in their hearts from what they see there! Quite often, one such visit was enough to put their unbelief or indifference to the test.

Moreover, are there really only a few cases where they felt how their inner world was shaken when they left the sacred monasteries, reborn after a few days or hours there?

Any monastery is a true oasis in the arid desert of this present life, especially of modern life… Especially for the nearest towns and villages, every monastery is a set of lungs delivering spiritual oxygen. And Holy Mount Athos is the “lungs” for all of Greece, and for the whole world!

Let the monks not go out into the world. The world comes to them. Let monks take shelter in enclosed places. Their light shines and illuminates everything around; and sometimes it illuminates even that which is far away. Let them talk little. There is also the “silent eloquence of a holy life.”

Brothers, let there be monasteries! But let’s pray that they might be worthy of their calling. And then, by some Divine law, they will automatically become like missionary centers, spiritual beacons, oases of souls, Divine hotels for many who fell among thieves (Lk. 10:30). The world can benefit greatly from monasteries.

The third way: Even if he is silent and hidden, a monk is a shouted sermon—a sermon not in words, but deeds; a sermon strong and astounding.

Brothers, what do missionaries, that is, those who work in the Church, proclaim in their sermons? What do they write about in their books, what are their topics? What do they prompt us to do? To love God, to pray, to fight against vice, to commune of the Holy Mysteries, to repent of our sins, to be humble, not to cling to material goods, to have a home in Heaven, and so on and so on.

But doesn’t a monk proclaim the exact same thing—not in words, but by deeds and example?

I if decide to become a monk, a true monk, it means love for God—Divine eros—consumes my entire being. (It’s understood that such love is found mainly and principally among monks, but it can’t be said that only and exclusively a monk has such love and no one else. Such a statement would be one-sided, unacceptable for Orthodoxy. We have already said that the Holy Spirit distributes gifts as He pleases. St. John of Kronstadt, for example, was a “secular” priest. But who could deny the fiery Divine love burning in his sanctified heart?) Prayer is the water and air of my soul. The Church’s Mysteries are my daily food. Repentance is my whole life’s work. My “I” is condemned to death. I disdain material goods. I count all things … but dung, that I may win Christ (Phil. 3:8). Wealth, prosperity, position, honor, and glory don’t concern me. I pass them by. My steadfast gaze is fixed upon the Heavenly Jerusalem…

So, when you hear that your friend, neighbor, relative, or friend left the world and departed to a monastery, isn’t that the same as hearing a resounding and deafening sermon about everything above, especially if the one who left possessed wonderful qualities and could have had great “success” in this life?

Your friend left in silence. You didn’t see him before he left, he didn’t say goodbye. But his act, a heroic act, an act of the greatest sacrifice for the sake of the love of God, speaks for itself. His footsteps sound forth quite clearly as he walks out the door, and will never trail off. You’ll hear the sound your whole life.

You’ll never see your friend again, or hear about his death when he dies. The memory of him won’t leave you alone. You’ll always have a saving turmoil and a holy uneasiness from it. It will constantly rebuke you. You’ll think:

“I can’t fast on Wednesdays and Friday, but he… I didn’t even commune on Pascha this year, but he… I have to force myself to barely say two words of prayer, but he… I earn a lot of money, I amass a great fortune—and I’m afraid to give a little to the poor, but he… I lie and flatter in order to rise up in society, but he… I chase after honors and fame, but he… I cling to the ground, but he…”

But even if you’re an unbeliever or indifferent, this act of your friend, in addition to the surprise it causes, will continuously chip away at the foundation of your unbelief or indifference. You’ll be thinking about this act in a moment of spiritual sobering up, and perhaps in a moment of frustration and disappointment in the “joys of the world,” and you’ll hear an inner voice asking you:

“The faith that inspires such sacrifices—perhaps it’s not just a product of fantasy? The faith that makes you happy when you deny and reject everything that others consider important—that is, pleasure, money, convenience, success, glory, and so on—maybe the truth is there? Perhaps there is life after death? Maybe the decision of your friend—who is otherwise so intelligent and gifted—isn’t a heroic “madness,” but a very “profitable undertaking?” Maybe he really did find the pearl of great price (Mt. 13:46) that that book called the Gospels tell us about?...”

This and other similar things will be proclaimed to a great many people by the example of a monk. Who will dare claim that this silent, but also thunderous “sermon” doesn’t “break bones,” according to the well-known expression?

This sermon isn’t theoretical, but practical. It doesn’t last a few minutes, but strikes your ear continuously. It literally follows you! The monk, taking up the Cross and following Christ, TEACHES BY DEED—and teaches loudly—“to disdain the flesh, as something transient, but to care for the soul as something immortal.”[2]

So, is a monk or is he not, by his example alone, a herald of eternity?

Is he or is he not an indication of the path to Heaven?

Is he or is he not a preacher and missionary?