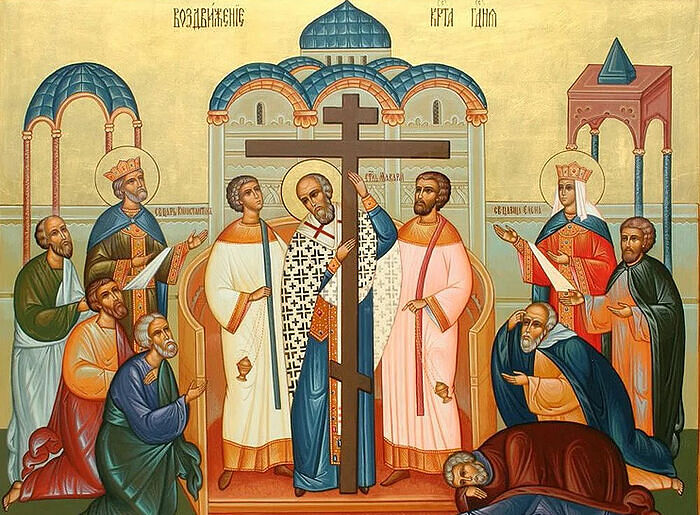

In the fourth century, events took place that radically changed the entire course of world history and the development of culture and civilization. The Christian faith was legalized and then became the state religion. These transformations that had begun could be symbolized in the finding of the Life-giving Cross of the Lord, which took place in Jerusalem in either 325 or 326.

Ten years later, on the site of Golgotha and the Savior’s Tomb, a church was erected with the direct participation of Emperor Constantine himself, and his mother Helen. The day of the consecration of the church began to be celebrated annually with special solemnity. By the end of the fourth century, this memorial had already become one of the three main feasts, together with Pascha and Theophany, continuing for eight days. The feast of the Exaltation of the Cross began to be celebrated only in the fifth century, on the second day after the feast of the consecration of the church, when the Cross would be shown to the people.

In other words, at first, the Exaltation was just an addition, accompanying the feast of the Consecration of the Church in Jerusalem.

The faithful began to pay more attention to the events of the Exaltation of the Cross only in the sixth century, as evidenced by the liturgical and theological texts of the time that have been preserved. The feast of the Exaltation of the Cross gradually became the main one, while the commemoration of the consecration of the church faded into the background, and became the forefeast of the Exaltation. Scholars connect this, first and foremost, with the sorrowful events of the destruction of Jerusalem by the Persians in the eighth century. Theologian and Church historian Mikhail Skaballanovich offers this theological explanation:

This instrument is worthy of such a celebration, of an independent feast in its honor, not only because of the significance it had in the act of redemption itself, not only in view of the importance that it acquired over time in the life of Christians, but also because of what it was for Christ Himself.[1]

The texts for this feast are filled with numerous symbols that glorify the instrument of Christ’s victory over death, revealing the soteriological aspects of theology and speaking of the priceless gifts that believers have acquired through the salvific death of Jesus.

Let’s examine several of the hymnographic texts of the feast that colorfully confirm this.

“Bless Thine inheritance…”

The troparion of the feast is well-known and quite popular in the Orthodox world. It’s found in the morning prayer rule and the moleben for the blessing of water. As Skaballonovich notes:

It is the only troparion of the twelve feasts that is a continuous prayer, fully corresponding to the nature of the feast.[2]

The beginning is borrowed from the ninth verse of Psalm 27, which expressed the Israelite people’s expectation of the coming of the Messiah. And Christ, having come into the world, saved all mankind from death.

This is how the troparion reads now:

O Lord, save Thy people, and bless Thine inheritance. Grant victory to the Orthodox Christians, over their adversaries, and by virtue of Thy Cross, preserve Thy habitation.

Before the 1917 Revolution, after “victory,” the Church Slavonic text read: “to our pious Emperor (name).” The Greek text has preserved this:

“νίκας τοῖς Βασιλεῦσι κατὰ βαρβάρων δωρούμενος” (grant victory to Kings over the barbarians).

The troparion contains a prayer for the entire people (“inheritance”), and also for the state and government.

In other words, this prayer entreats God’s mercy for all the faithful and the preservation of their unity. Of course, there is also some politicization of the text here, expressing the idea of the special place of the Byzantine Empire and its ruler. Later, this passed into the Russian Tradition as well.

“O Thou Who wast lifted up willingly on the Cross”

The kontakion of the feast is identical in content to the troparion—a prayer for the preservation of the people of God. Skaballanovich calls this hymnographic text a semantic development of “O Lord, save Thy people,”[3] where “our right-believing Emperor (name)” was also added in the times of the kings.

The text of the kontakion reads:

O Thou Who wast lifted up willingly on the Cross, bestow Thy mercies upon the new community named after Thee, O Christ God; gladden with Thy power the Orthodox Christians, granting them victory over enemies; may they have as Thy help the weapon of peace, the invincible trophy.

The kontakion emphasizes that Christ offered the sacrifice of the Cross for the sake of love for all mankind, and therefore it was a free action. This is a fundamental moment in the work of the salvation of the world.

“Those who are called by Thy name,” are, of course, Christians.

“New community” is “πολιτεία (state, polity)” in Greek. On the one hand, we’re talking about an Orthodox state here, which the faithful ask to be protected; and on the other hand, it can be understood as the “New Israel,” the people of God, consisting of the followers of Christ, regardless of national origin.

As confirmation of this idea, we can cite the fact that one of the meanings of the Church Slavonic term used here, “жительство,” is “way of life,” that is, life according to the Gospel commandments, which is defining for Christians. Although, of course, the hymnographic text under consideration here is first of all a prayer for the earthly Fatherland.

“We exalt His name…”

I’d like to consider other liturgical texts as well that are heard in church on the feast of the Exaltation of the Cross.

In the verse sticheron on “Lord, I Call,” the hymnographer reveals the meaning of the feast and of such a reverent attitude to the instrument of execution of the Messiah Who came into the world:

We raise on high the Cross which exhorteth all creation to hymn the all-pure Passion of Him that was lifted up thereon. For thereon having slain him that slew us, in that He is merciful, He gave life unto the dead, and in the exceeding greatness of His goodness He hath adorned them with beauty and vouchsafed them to live in the heavens. Wherefore, rejoicing, we exalt His name, and magnify His extreme condescension.

The text begins with an indication of the essence of the feast—the Exaltation of the cross: “We raise on high the Cross.”

The event itself, which occurred at the beginning of Church history, compels us to hymn and glorify Christ, Who offered Himself as a sacrifice for the sake of the salvation of all mankind. The Church Slavonic text uses the verb “повелевает,” which means not only a direct order to fulfill something, but is also connected with motivation, or compulsion. This meaning corresponds to the Greek “προτρέπεται” (“to incline, to exhort).

The sticheron uses the very familiar term “Passion” to refer to Christ’s torment on the Cross.

It also contains some words that are important for Church dogmatics: “having slain him that slew us.” Christ came into the world to defeat him who through the temptation of Adam brought an inclination towards sin and death into the world. As Metropolitan Hilarion (Alfeyev) notes:

“He [Adam, and in his person the whole of humanity—L.M, P.S.) not only lost the blessedness and sweetness of Paradise, but the whole nature of man has changed and been distorted. Having sinned, he fell away from the natural state, entering into a state against nature.”[4]

By His coming into the world, the Lord made it possible for man to restore the eternal life with the Creator that was lost at the very beginning of history, which the sticheron then talks about:

He gave life unto the dead, and in the exceeding greatness of His goodness He hath adorned them with beauty and vouchsafed them to live in the heavens.

This “adorned with beauty” corresponds to the Greek “κατεκάλλυνε,” meaning to be cleansed from vice, from the consequences of Adam’s Fall, and to be transfigured.

This is the central moment in the work of our salvation, because without redemption, man would remain incomplete, wounded, unable to perfect Himself in God.

“Moses prefigured Thee…”

Another sticheron on “Lord, I Call” reads:

Moses prefigured thee, O precious Cross, when he stretched out his hands on high, and put the tyrant Amalek to flight. Thou art the boast of the faithful, the support of those who suffer, the glory of the Apostles, the champion of the righteous, and the salvation of all the saints. Therefore, beholding thee raised on high, creation rejoices and celebrates, glorifying Christ Who has joined together through thee that which was divided in His infinite goodness.

This sticheron is dedicated to one of the Old Testament’s prototypes of the Life-giving Cross. During the battle with the Amalekites, Moses went up a mountain, where he prayed with hands raised. As long as his arms were raised, the people of God would be winning, but when he let them down, the opposite happened. Seeing this, Aaron and Hur, who accompanied the prophet, started supporting his arms (Ex. 17:8-13). Exegetes of this story tend to see an allusion to the Savior’s Cross here. Thus, St. John Chrysostom exclaims:

See how the image was given through Moses, but the truth is revealed through Jesus Christ… When Christ came, He Himself stretched out His arms upon the Cross.[5]

If the prayer of the historian could save from death in an earthly battle, then the Golgotha sacrifice is salvation for all of mankind, regardless of position, spiritual state, nationality, etc., which is directly stated in the hymnographic text we’re examining. The author of the sticheron uses the following characteristics of what the Cross is to the faithful follower of the Savior: “boast,” “support” (“protection”), “glory,” “champion,” and “salvation.”

“Let us proclaim today a festival of song…”

If the stichera on “Lord, I Call” addresses Christ and His Cross, then the stichera at the Litya address us, the faithful who have come to the feast to glorify the Savior:

Let us proclaim today a festival of song, and with radiant faces and with our tongues let us cry aloud: O Christ, Thou hast accepted condemnation for us, and, being spat upon, and scourged, Thou wast robed in purple and didst ascend the Cross. Seeing Thee, the sun and the moon hid their light, the earth quaked in fear, and the veil of the Temple was torn in two. Grant us Thy precious Cross as our guardian and protector, driving demons away, that we may all embrace it and cry out: “Save us, O Cross, by thy might! Sanctify us by thy radiance, O precious Cross, and strengthen us through thine Exaltation; for thou hast been given to us as the light and salvation of our souls!

Into the mouths of all believers are placed words about the greatness of Christ’s sacrifice, about the humiliations, trials, and sufferings that He endured for the salvation of the entire world. The sticheron retells the Gospel description of the end of Jesus’ earthly life. The Cross acts as our intercessor in our growth and spiritual struggles. “Sanctify us by thy radiance,” that is, cover us with the glory of the atoning sacrifice.

***

Thus, all the hymnographic texts of the feast of the Exaltation of the Cross of the Lord glorify the weapon through which the Lord brought all of mankind to eternal life with Him and healed the consequences of original sin. Like any liturgical works, they have an important theological content and allow the faithful to come into contact with the mystery of salvation.

This day calls Orthodox Christians to remember the sacrifice that Jesus offered for the sake of every man, to reflect upon God’s love for us, and to again and again try to change our lives.