Isaac Levitan: “Above Eternal Peace” (1894)

Isaac Levitan: “Above Eternal Peace” (1894)

Archpriest Seraphim Gan is the rector of St. Seraphim’s Church in Sea Cliff, NY, and a member of a famous family in ROCOR.

“Another destiny awaits your daughter”

Dear Olga, you have asked me some questions about Divine Providence in the life of my family, and I will try and answer your questions and share with you some amazing stories from our family tradition.

Divine Providence always acts in our lives, more often invisibly, and we can understand it by looking back into the past. Sometimes Providence works explicitly: through the blessing of a spiritual father, other spiritual people or the pious, believing parents whom we obey.

In the mid-nineteenth century, a peasant woman from the Vyatka province, went on pilgrimage to the holy monasteries and convents of Russia together with her teenage daughter Maria, and prayed fervently in several of them. The pious mother dreamed of monastic life for her daughter and, meeting an elderly hieromonk in the Holy Dormition Monastery in the town of Tikhvin of the province of Novgorod [now in the Leningrad region—Trans.], she turned to him with a heartfelt request:

“Dear batiushka, bless my daughter Maria to join a convent!”

The wise elder was slow to give his blessing. Having prayed earnestly that the Lord would reveal His will to him, he answered the woman:

“Another destiny awaits your daughter. Years will pass—and the peasant girl Maria will marry, and her children will be monastics or have the dignity of ordination.”

And that is what happened. The young lady Maria obeyed the elder and her mother: she grew up, married the peasant Kelsiy (Celsus) Kilin (the priest gave him this name according to the Church calendar—in honor of the holy Martyr Celsus) and became the mother of several children.

The elder son of Maria Kilina, Ivan Kelsievich Kilin, became Archbishop Juvenaly (Kilin; 1875—1958), the builder and abbot of the Monastery of the Kazan Icon of the Mother of God in Harbin. The younger son became a priest. The younger daughter, Nun Aglaida, filled with a feeling of monastic humility, ended her days in a convent. And finally, the elder daughter of Maria Kilina was my great-great-grandmother. She married Vasily Yumin and herself became the mother of two sons: Alexander Vasilyevich and Konstantin Vasilyevich Yumin. Hieromartyr Konstantin Yumin was my great-grandfather.

“My daughter, get ready for May 26”

The daughter of Hieromartyr Konstantin Yumin, my grandmother Sophia Konstantinovna Yumina, was born in 1911 in Russia and reposed in the Lord in 1991 in Sydney at the age of eighty. She saw a lot in her life: the Perm province, Siberia, China, Australia...

My grandmother remembered her beloved father when he was very young: she was a child when he was arrested and sent to prison only because he was a priest. When little Sophia, together with her mother Olga Yumina, came to visit their father and husband, the jailers unexpectedly and quite mercifully allowed the priest to say goodbye to his family. In the end, they decided to show mercy to him before they shot him.

For the rest of her life, Sophia remembered the mournful expression on the face of her beloved father: in just a few days of imprisonment, the very young man had turned gray. As he looked at his beloved wife and daughter, he realized that he was seeing them for the last time. And there was so much love and tenderness in his parting gaze that my grandmother remembered it for all of her life.

My great-grandfather was given a funeral service and buried in accordance with Orthodox tradition. My grandmother even visited his grave, on which a simple wooden cross was erected.

Once, when she was already in Australia, she shared a story with me, her grandson, which she told few people. Several years after the execution of her father, my grandmother had a dream in which she came to weep and pray at her father's grave and heard his gentle voice:

“My daughter, get ready for May 26!”

These words didn’t frighten the young Sophia. She accepted them as fatherly care—as though her beloved father were continuing to look after her even after his death.

The Holy Fathers edified believers with the words: “Maintain the remembrance of death, and you will never sin.”

This virtue—maintaining the remembrance of death—was granted to my grandmother Sophia Konstantinovna by her father. In addition to observing the usual fasting, she always tried to fast in the second half of May. She also tried to receive Holy Communion on May 25 or 26 in order to be ready to pass into Eternity.

Early one morning in 1991, my father came into my room (at that time I was sixteen). We lived in California, and my grandmother lived in Sydney. My father said:

“There was a phone call from Sydney: your grandmother passed away today.”

I recalled my grandmother's dream and looked into the calendar: it was June 8. At first, I decided that the dream hadn’t come true, but then figured out that my great-grandfather had warned about May 26 according to the old calendar! I counted the days and made sure that May 26 is June 8 according to the new calendar. My grandmother was able to confess and commune before her death. This is how parental love and prayer cover us even after our parents leave for another world...

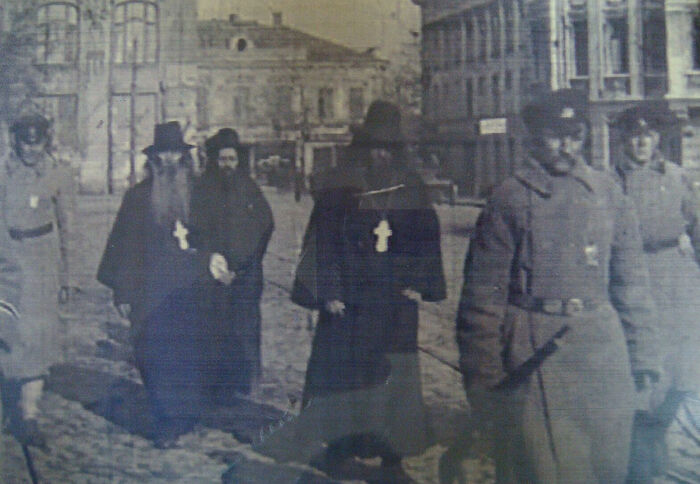

Arrested priests are taken to the Cheka, 1920

Arrested priests are taken to the Cheka, 1920

In memory of my great-grandfather

I would like to say a few words about my great-grandfather in his memory. Konstantin Vasilyevich Yumin was born in 1889 to the family of the bailiff Vasily Yumin. He had a younger brother, Alexander, who had a slight limp, a weak physique and a small stature. The brothers were very close; both graduated from the theological school in Sarapul [a city in the Udmurt Republic within Russia—Trans.] (as did their uncle, Archbishop Juvenaly), and then entered the Perm Theological Seminary.

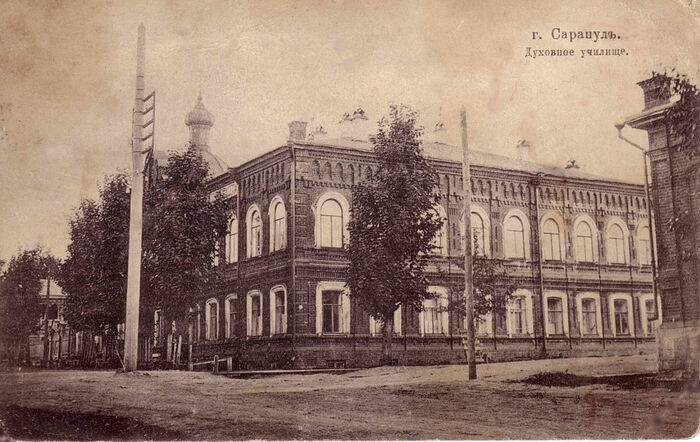

The Sarapul theological school

The Sarapul theological school

The Perm Theological Seminary was old: it was founded in 1800. In 1900, when the seminary celebrated its centenary, it was considered one of the best theological schools in Russia. In addition to theological subjects, natural sciences and humanities, ancient languages (Latin and Greek) and modern languages (French, German) languages were taught there. Special attention was given to training missionaries, teaching history and denouncing the Old Believer schism. Its seminarians also studied medicine and learned to administer the smallpox vaccination, since most of them later served in rural parishes where the priest was often the only educated person.

In those years they entered the seminary at the age of fourteen, and their studies lasted for six years. Friendly and diligent in their studies, the Yumin brothers graduated from the seminary in 1909 at the second level, meaning they had received “good” and “excellent” grades.

A classmate of my great-grandfather at the seminary, Vasily Alexeevich Ignatiev (1887—1971), recalled:

“The Yumin brothers were kind, warm-hearted comrades. They were cheerful young men, especially Alexander who loved to laugh and joke. After graduating from the seminary, Konstantin was ordained, and Alexander worked as a teacher in a four-year school in the city of Kamensk-Uralsky [in the Sverdlovsk region.—Trans.] where he taught literature with great success.”

A lively and cheerful graduate of the seminary, Alexander Vasilyevich Yumin taught his students about spiritual things and interpreted literary works from the point of view of the Christian faith, though this was punished with great cruelty in those years. The younger brother of my great-grandfather was arrested in 1920.

Vasily Alexeevich Ignatiev wrote about it:

“At a certain point Alexander Yumin ‘was caught,’ after which there was no information about him."

Using the words “was caught,” he was referring to the Irmos of Ode 6 from the Matins of Holy Saturday—“Jonah was caught but not held fast in the belly of the whale”—about how the Prophet Jonah ended up in the belly of a whale. So Vasily Alexeevich expressed himself allegorically (as was proper in the Soviet era) implying that Alexander Yumin had been arrested and repressed. After his arrest no one ever saw him again—he was most likely shot immediately in 1920.

Two years earlier, in 1918, the Perm Theological Seminary had ceased to exist as well: its building was confiscated for the needs of the Cheka [the All-Russian Extraordinary Commission for Combating Counterrevolution and Sabotage—Trans.]. The rector of the seminary, Archimandrite Matthew (Pomerantsev), was brutally killed by the Red Army (and is now ranked among the New Martyrs).

The Arrest of Patriarch Tikhon. Artist: Philip Moskvitin

The Arrest of Patriarch Tikhon. Artist: Philip Moskvitin

My great-grandfather's pastoral ministry

My great-grandfather Konstantin Vasilyevich Yumin graduated from seminary as a twenty-year-old young man, and a year later he married a pious girl named Olga, my future great-grandmother. They had a daughter, Sophia (my grandmother), and a son, Anatoly.

My great-grandfather was ordained as a priest in 1913 by Archbishop Andronik (Nikolsky; 1870—1918), the future martyr. His murderers, the Cheka officers, forced Vladyka to dig his own grave and lie down in it, after which they threw earth at him, shot at the lying archpastor several times and filled up the grave. The martyr may still have been alive when he was buried.

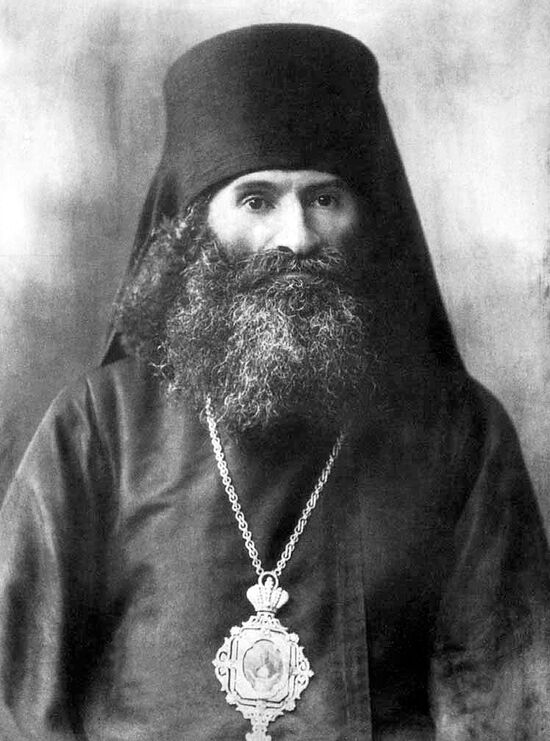

Hieromartyr Andronik (Nikolsky)

Hieromartyr Andronik (Nikolsky)

Starting in 1913, my great-grandfather, Father Konstantin Yumin, served at the Church of the Nativity of the Mother of God in the factory village of Dobryanka in the Perm province about forty miles away from the provincial capital. The church where my great-grandfather served and where his wife and children prayed was wonderful. It had three altars: dedicated to the Nativity of the Most Holy Theotokos, St. Alexander Nevsky and St. Nicholas the Wonderworker, and it had around 7,000 parishioners from Dobryanka and sixteen neighboring villages. The relics of the church included ancient “family” icons of its benefactors and builders—the Stroganov family—along with a Gospel from 1606. It also had an excellent library with 600 volumes of spiritual literature and a stone bell-tower.

The center of old Dobryanka and the Nativity of the Mother of God Church

The center of old Dobryanka and the Nativity of the Mother of God Church

All this was destroyed or looted after the Russian Revolution. At that time, my great-grandfather was executed by firing squad. The crosses were thrown down from the church, the bell-tower and the dome were demolished, and the named bells with dedicatory inscriptions were sent off as scrap metal. A cinema named after Voroshilov was opened in the building of the former beautiful church. Later it became home to a community center with a dance hall and a cafeteria.

The wonderful city of Harbin

My great-grandmother Olga Grigorievna Yumina went to Siberia with her children and then ended up in Harbin. In Harbin, a Russian city on Chinese soil, the old order of the imperial era was preserved for a long time—as though pre-revolutionary Russian life had been “mothballed.” Olga Grigorievna settled there with her son Anatoly and daughter Sophia, my future grandmother. The young widow got a cow to provide milk for her family. When Sophia got married and gave birth to my father, Olga Grigorievna supplied them with milk, so the little boy called her “granny Moo.”

In 1935 in Harbin, the uncle of Olga Grigorievna's murdered husband (Hieromartyr Konstantin Yumin), Archimandrite Juvenaly (Kilin) was consecrated as Bishop of Xinjiang. He was also the builder and abbot of the Monastery of the Kazan Icon of the Mother of God. Vladyka Juvenaly took care of his nephew's family: his widow and his own grand-nephews Anatoly and Sophia, my young grandmother.

The Monastery of the Kazan Icon in Harbin

The Monastery of the Kazan Icon in Harbin

A “Rooster” and Kurochkina

Thus far I have spoken about relatives of my grandmother Sofia Yumina’s line. Now I will say a few words about the relatives of my grandfather, Archpriest Rostislav Gan.

His father, my great-grandfather, came from a family of long-ago Russianized Germans, and his name was Adolf Alexandrovich Gan. Even the German surname of his ancestors, “Hahn,” had been long before transformed into an easier one for Russian speech: “Gan.” Interestingly, “Hahn” means “rooster” in German, and my great-grandfather married a young woman named Seraphima Nikolaevna Kurochkina (1888-1961), with “kurochka” meaning “little hen” in Russian! She was a teacher from Osa, a small town in the Perm province, and he was the captain of the Fourth Trans-Amur Railway Battalion of the Border Guard of the Chinese Eastern Railway (CER). In those years, the staff captain corresponded to the ninth of fourteen ranks of the Table of Ranks [a system instituted by Peter I in 1722.—Trans.].

In 1911, the only child—my grandfather, Rostislav Adolfovich—was born to Adolf Alexandrovich and Seraphima Nikolaevna Gan. The Gans then lived at the Zalantun weather station of the western line of the CER.

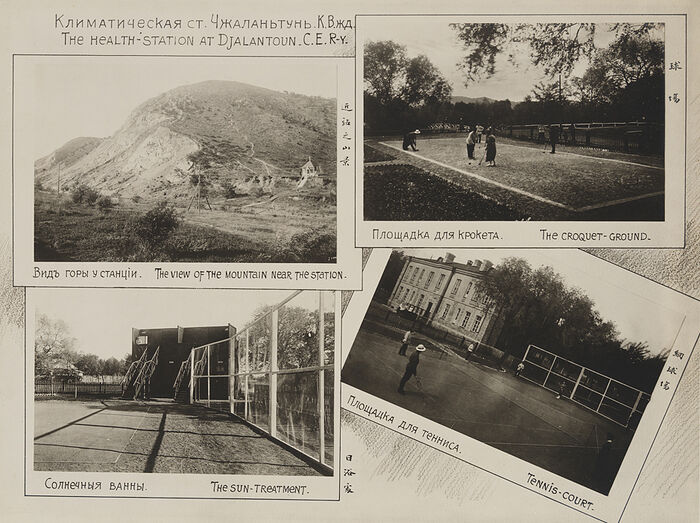

The Zalantun Station: the train station and a cafeteria

The Zalantun Station: the train station and a cafeteria

In those years, in picturesque areas of the line the Medical Department of the CER set up a number of resorts, or “weather stations,” as they were dubbed at that time.

The Zalantun Station: my grandfather was born there

The Zalantun Station: my grandfather was born there

Life at the Zalantun Station was going quite well. Perhaps my grandfather would not have been the only child in the family if the terrible events of World War I had not begun, followed by the Revolution and the Civil War.

During those terrible years, my great-grandfather was sent to serve in Tiflis [the name of Tbilisi until 1936.—Trans.]. There he disappeared. There was no news about him, and my young great-grandmother and her son didn’t know what had happened to their dear and beloved husband and father for many years.