Picture 1: The Resurrection of Jesus Christ. A twelfth century Miniature. Getty Museum “The Resurrection of Jesus Christ” (the Anastasis) (Pic. 1) and “the Descent into Hades” are two different images that developed in different cultures—Byzantine and Latin—and are not connected with each other by their history or iconography.1

Picture 1: The Resurrection of Jesus Christ. A twelfth century Miniature. Getty Museum “The Resurrection of Jesus Christ” (the Anastasis) (Pic. 1) and “the Descent into Hades” are two different images that developed in different cultures—Byzantine and Latin—and are not connected with each other by their history or iconography.1

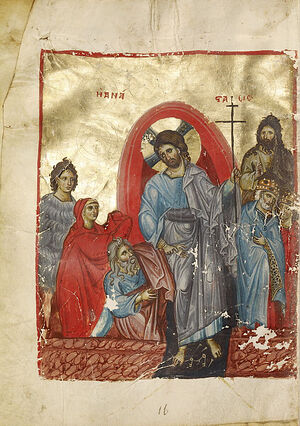

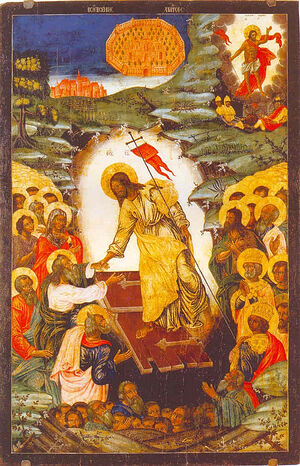

The image of “the Resurrection of Jesus Christ” appears in Byzantium before the sixth century. The image of “the Descent into Hades” appears in the ninth century (first as part of the illustration of The Apostles’ Creed, and only after the Great Schism as a separate image [Pic. 2]).

The scenes of these two images are different. The Anastasis takes place in the Heavenly realm: this is the moment of the Resurrection of Christ, His triumph over death, complete victory over hell and the devil, and the return of Paradise to man. “The Descent into Hades” takes place in the netherworld, which the Savior enters and is about to destroy.

How could these two so different images be associated with each other?

The answer to this question can be found in the history of the art of the sixteenth to the seventeenth centuries, when Western European influences became strong in Russia.

Picture 2: the Descent into Hades. Miniature of the Winchester Psalter. British Library.

Picture 2: the Descent into Hades. Miniature of the Winchester Psalter. British Library.

Namely, when icon-painters begin to use Western European engravings as models for creating new icons. Protestant albums of engravings and illustrated Bibles appear in Russia. At the moment of its confrontation with Catholicism, Protestantism once again turns to the Apostles’ Creed, which is presented on Protestant engravings. This creed, despite its name, is later than the Niceo-Constantinopolitan and takes on special significance under Charlemagne in the ninth century.

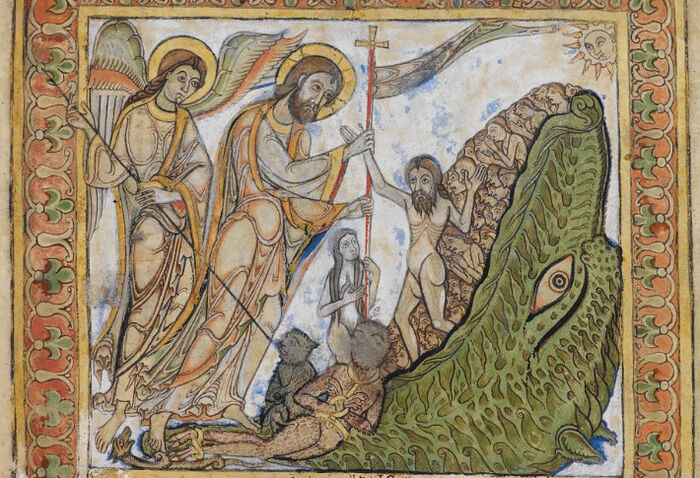

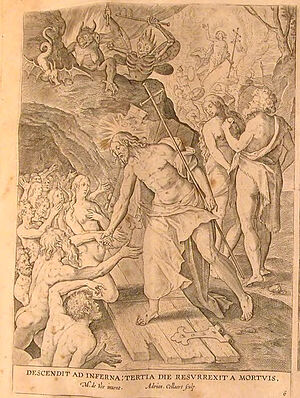

Picture 3: the Resurrection from the Tomb. Engraving from the Gospel cycle of the Piscator’s Bible The history of the illustration of the Creed in Western European art is a separate complex topic, which we will not touch on here.2 We will only note that it underwent a complex and lengthy evolution. For the longest period, each dogma from the Creed was illustrated separately and presented on a separate miniature. In the sixteenth century the tendency to unite all the dogmas named in a certain article of the Creed into one image was developed. “The Annunciation” and “the Nativity”, or “the Crucifixion” and “the Entombment”, named in the same article, Are united in the same engraving. Thus, the engraving for the fifth article combines “the Descent into Hades” and “the Resurrection from the Tomb” (a Western European image of the Resurrection, not typical for Byzantine and ancient Russian art).

Picture 3: the Resurrection from the Tomb. Engraving from the Gospel cycle of the Piscator’s Bible The history of the illustration of the Creed in Western European art is a separate complex topic, which we will not touch on here.2 We will only note that it underwent a complex and lengthy evolution. For the longest period, each dogma from the Creed was illustrated separately and presented on a separate miniature. In the sixteenth century the tendency to unite all the dogmas named in a certain article of the Creed into one image was developed. “The Annunciation” and “the Nativity”, or “the Crucifixion” and “the Entombment”, named in the same article, Are united in the same engraving. Thus, the engraving for the fifth article combines “the Descent into Hades” and “the Resurrection from the Tomb” (a Western European image of the Resurrection, not typical for Byzantine and ancient Russian art).

In the Protestant Piscator’s Bible (Piscator was a seventeenth-century Dutch engraver and publisher), the image “the Resurrection from the Tomb” (Pic. 3) is placed in the section illustrating the gospel narrative, which is still unusual for Orthodox art. Therefore, when creating the icons, “I Believe”, or those depicting the Resurrection, Russian icon-painters turned to the next section of this Bible—illustrations of the “Apostles’ Creed”—and used its fifth engraving. The fifth article of the Orthodox Creed speaks of the Resurrection of Christ; the fifth article of the Apostles’ Creed speaks of two events—Christ’s Descent into Hades and Resurrection.

However, icon-painters use the engraving of the Creed without assuming the possibility of another Creed different from the Orthodox one.

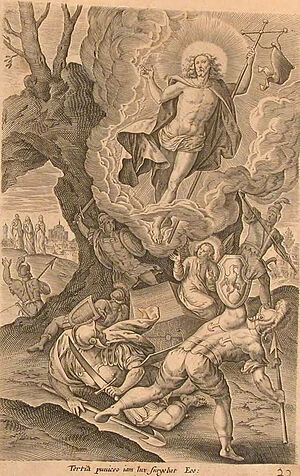

Picture 4: Illustration of the fifth article of the Apostles’ Creed from the Piscator’s Bible The engraving illustrating the fifth article depicts two events: the descent of Christ into hades and His Resurrection in Western European iconography as rising from the tomb. The descent is shown here as it began to be depicted in Italian art (the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries), without the mouth of hell (Pic. 4). It is this engraving that Russian icon-painters begin to copy, giving it iconographic features.

Picture 4: Illustration of the fifth article of the Apostles’ Creed from the Piscator’s Bible The engraving illustrating the fifth article depicts two events: the descent of Christ into hades and His Resurrection in Western European iconography as rising from the tomb. The descent is shown here as it began to be depicted in Italian art (the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries), without the mouth of hell (Pic. 4). It is this engraving that Russian icon-painters begin to copy, giving it iconographic features.

This is how the image that is characteristic of Russian art appears, created as a copy of an engraving where two images, “the Descent into Hades”, and “the Resurrection from the Tomb” are combined, which is typical for the Creed, different from the Orthodox one. It could be said that here the image of “the Descent into Hades” (the sixteenth to the seventeenth centuries) for the first time becomes part of Orthodox art. But here it is necessary to take into account that icon-painters simply might have misunderstood its meaning and interpreted it in a different way.

The stages of adopting new iconography

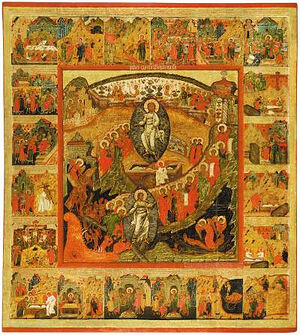

Picture 5: Micah and Sabbas the Slovenians. Resurrection from the Tomb with the Descent into Hades. 1764. Kostroma State Historical, Architectural and Art Museum-Reserve The confirmation of the fact that the sixteenth and seventeenth century icon-painters did not understand properly what was depicted on the engraving can be seen in the iconography of the new image, “the Resurrection from the Tomb with the Descent into Hades.” On earlier similar icons we see not an exact copy, but a modification that reflects the icon-painter’s interpretation. Since he perceives the first image as corresponding to “the Anastasis”, he places it above the image of the Resurrection from the Tomb. The scene of the image, “the Resurrection from the Tomb” is our realm and earthly reality, and the sixteenth and seventeenth century icon-painters place it in the lower right corner—copying the engraving, but changing its composition.

Picture 5: Micah and Sabbas the Slovenians. Resurrection from the Tomb with the Descent into Hades. 1764. Kostroma State Historical, Architectural and Art Museum-Reserve The confirmation of the fact that the sixteenth and seventeenth century icon-painters did not understand properly what was depicted on the engraving can be seen in the iconography of the new image, “the Resurrection from the Tomb with the Descent into Hades.” On earlier similar icons we see not an exact copy, but a modification that reflects the icon-painter’s interpretation. Since he perceives the first image as corresponding to “the Anastasis”, he places it above the image of the Resurrection from the Tomb. The scene of the image, “the Resurrection from the Tomb” is our realm and earthly reality, and the sixteenth and seventeenth century icon-painters place it in the lower right corner—copying the engraving, but changing its composition.

Then, in later seventeenth to eighteenth century monuments, “the Resurrection from the Tomb with the Descent into Hades” is depicted as an exact copy of the engraving: the location of the subjects relative to each other is preserved (Pic. 5).

A new iconography is characteristic for the eighteenth and the nineteenth centuries, where the figure of Christ is twice located along the central vertical (Pic. 6). We see a stable compositional dominant, with other events grouped around it.

This includes not only events mentioned in the Gospel, but also apocryphal stories (of the Wise Thief, the visit of St. Mary Magdalene to Emperor Tiberius, the story of the Ubrus, etc.). An analysis of the composition of these subjects allows us to name as their source “the Passion of Christ”—a translated work from Western European literature, which became widespread in Russia from the seventeenth century on and popular among ordinary people, not the least among Old Believers.3

Picture 6: “Resurrection—Descent into Hades”, with gospel scenes In the nineteenth century, official Church art was oriented towards academic models. The Western European image, “the Resurrection from the Tomb”, becomes very common—we see it in the main cathedrals of the Russian Empire. But both the icon “the Resurrection of Jesus Christ” (the Anastasis) and the multi-figured icon “the Resurrection from the Tomb with the Descent” continue to exist among ordinary people.

Picture 6: “Resurrection—Descent into Hades”, with gospel scenes In the nineteenth century, official Church art was oriented towards academic models. The Western European image, “the Resurrection from the Tomb”, becomes very common—we see it in the main cathedrals of the Russian Empire. But both the icon “the Resurrection of Jesus Christ” (the Anastasis) and the multi-figured icon “the Resurrection from the Tomb with the Descent” continue to exist among ordinary people.

The situation changes with the construction of the Church of the Resurrection in St. Petersburg (the Church of the Savior “On the Blood”), which, at St. Nicholas II’s request, was to be decorated in accordance with ancient iconography. The search for the origins began, but it was destined to end with the Russian Revolution.

Art history works published in the nineteenth century adopt a new designation of the image (for example, N.P. Pokrovsky uses “the Anastasis” and “the Descent into Hades” identically). This is how that “tradition” emerges, which at present seems to be “old”, and hence “time-honored”.

***

Picture 7: Resurrection of Jesus Christ. 1370s–1380s. Icon. State Russian Museum. Combining two so different images under one name, we lose the opportunity to explore the history of each of them. We obscure for ourselves the understanding of what is depicted on both. To call the image of the Resurrection, “the Descent into Hades”, is to imply that Christ has not yet risen here; it means slandering the icon and Orthodox culture, which perceives this image as an icon of Pascha. But, most importantly, in such confusion we lose the opportunity to perceive the Church’s answer the to the question of what the Resurrection of Christ means to us. This answer is given in Orthodoxy in the icon of this Feast—the icon of the Resurrection of Jesus Christ (Pic. 7).

Picture 7: Resurrection of Jesus Christ. 1370s–1380s. Icon. State Russian Museum. Combining two so different images under one name, we lose the opportunity to explore the history of each of them. We obscure for ourselves the understanding of what is depicted on both. To call the image of the Resurrection, “the Descent into Hades”, is to imply that Christ has not yet risen here; it means slandering the icon and Orthodox culture, which perceives this image as an icon of Pascha. But, most importantly, in such confusion we lose the opportunity to perceive the Church’s answer the to the question of what the Resurrection of Christ means to us. This answer is given in Orthodoxy in the icon of this Feast—the icon of the Resurrection of Jesus Christ (Pic. 7).