It seems to me that we don’t have enough fellowship as such in the Church today—just brotherhood. As one of my friends said: “We’re lacking in humanity.” To feel the warmth of another person near you, to communicate. It’s so interesting to get to know new people. The Church should be a family for a person. And a person should come to church with his or her family on Sunday. Or if a person doesn’t have a family, all the more so. Then the Church should basically be his or her home. Because some people go to church for ten, twenty, thirty years, completely alone. How can this be? To go to church and be alone. It’s not good. As you can see, it was different for the ancient Christians.

2:43 And fear came upon every soul.

What kind of fear was this? Obviously it wasn’t some kind of animal fear, but a pious, reverent fear. It was the kind of fear that comes on you when a miracle happens. It is fear as piety. In general, fear in the Holy Scriptures is a positive concept, not negative. The fear of the LORD is the beginning of wisdom, says David (Ps. 110:10). The fear of God is a virtue.

“Where there is fear, there is no love,” says the Apostle John the Theologian (cf. 1 Jn. 4:18). But this he says about the fear of a slave, comparing it with the highest love, the love of God. In general, love and fear can be combined. Let’s say a child is afraid of his dad, but loves him—he is afraid in the sense of not wanting to disappoint him. It isnot a panicky fear of him. The fear of God is an important virtue that we should ask for from God—the fear of God as a kind of feeling of God, awe before Him, the fear of God. A Christian is afraid to destroy his relationship with God, to darken it with sin. We’re afraid of anything but sinning. But everything should be the other way around. As they say: “I fear none but my God, and believe none but my God.”

2:44 And all that believed were together, and had all things common.

This is the original Christian community. As Mayakovsky said: “Everything in common, except toothbrushes.” The Bolsheviks, by the way, also wanted to make such a quasi-Christianity. But we know how this ended up.

And all that believed were together, and had all things common. And then it says what it means. They sold their estates and all kinds of property and divided it amongst everyone, depending on the needs of each. This is “Christian communism.” Of course, it didn’t last long. And we read about when it ended in the fifth chapter, where it talks about Ananias and Sapphira, when they had already sold their estate, but decided to keep a thousand or two for themselves—for a rainy day, as they say.

Of course, man can’t sustain life without his possessions, and even the original Christian Church couldn’t. And that’s not the point of Christianity anyways. But the motivation of the first Christians is clear—they thought the end of the world was nigh. Therefore, there was a reflex: If the Second Coming could happen any day, then really, what’s the point of having anything of your own?

Yes, these are very vivid eschatological expectations. The eschaton is the ultimate destiny of the world. The Christianity of the first century was the constant expectation of the end. Therefore, the very faith of the first Christians was closely connected with these apocalyptic expectations. That’s why Christians so easily gave up their property—they didn’t realize that all of this history would continue for a long time to come.

In his second epistle, the Apostle Peter explains why time is going by and Christ still hasn’t come. He had to explain it, because there were already people in his time who were asking: Where is the promise of His coming? for since the Fathers fell asleep, all things continue as they were from the beginning of the creation (2 Pet. 3:4). And St. Peter answers: The Lord is not slack concerning His promise, as some men count slackness; but is longsuffering to us-ward, not willing that any should perish, but that all should come to repentance (2 Pet. 3:9). Christ Himself said: It is not for you to know the times or the seasons (Acts 1:7). That is, wait and just do what you always have to do.

2:45 And sold their possessions and goods, and parted them to all men, as every man had need.

How did this work? Obviously, people sold everything and gave it for the needs of the Christian community. And who were the leaders of the community? The Apostles. But later we’ll read (in the third chapter) that when Sts. Peter and John healed a lame man at the Temple, the man looked at them in hopes of receiving alms, but St. Peter said: Silver and gold have I none; but such as I have give I thee (Acts 3:6), and he healed him. That is, the Apostles didn’t take the community’s funds for themselves.

So this first Christian impulse wasn’t communism at all. The internal content is different. Here is the expectation of the end of the world and life in expectation of the end. But this condition quickly came to an end. Firstly, everyone realized that this was all for a long time, and secondly, no one canceled human passions. There arose misunderstandings.

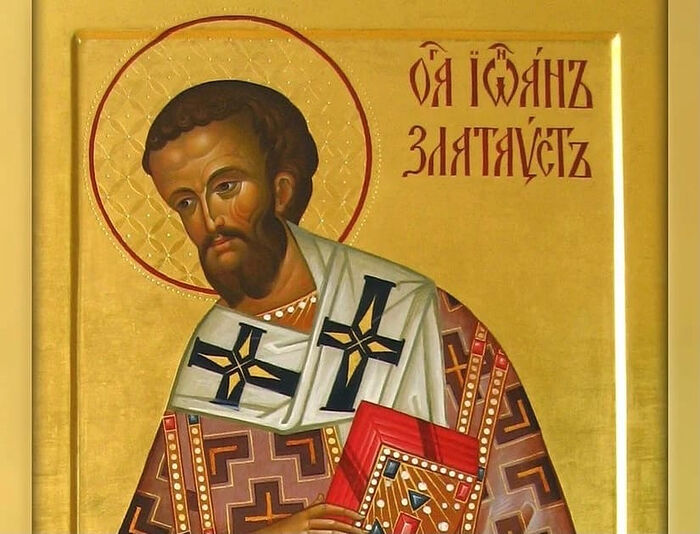

St. John Chrysostom also tried to implement these ideas in the fourth-fifth centuries. When he ascended the patriarchal throne, the first thing he did was to spend the entire treasury in a matter of days. Everything that was saved up for churches, some marble, other expensive materials, he spent all on the poor, building them a shelter. In general, there were no new churches, no domes—nothing. Then, he himself lived very ascetically. When a bishop would come to him, the Holy Hierarch would feed him with the same pea soup he himself would eat. There were bishops who would say: “I’ll remember you for this pea soup.” Well, and they remembered. St. John Chrysostom was convicted and sent into exile, where he died. He was condemned by his own bishops.

Why am I talking about this? St. John had this idea—to make all property ecclesiastical, and to give to everyone according to their need. He constantly talked about this in his homilies. He would say: “You rich, give everything to the Church. It’s not yours. It’s God’s. You’re just using it. If you don’t use it justly, you’ll be condemned; and the righteous thing is to give everything away and follow Christ.” He could easily talk about it since he himself had done it.

This, of course, is a collision of the pure Gospel with the Old Testament spirit of this world. This collision is a bit of a debacle for the Gospel, because in order to realize these ideas, everyone has to be holy. But St. John wanted to make all of Constantinople like this, so that all the rich would give everything away, so that the Church would care for the poor, and all property would be the possession of the Church. But, of course, this is completely unrealistic,because there are also sinful, passionate people in the Church. And wealth in the Church can also corrupt. Authority corrupts ordinary people, and spiritual authority—can you imagine what it can do to a man? But there are also riches here.

St. John was living at the time when the Church was first faced with the danger of enrichment. Before that, there was no such danger. The first, second, and third centuries were persecution. The fourth century—the Church gradually became imperial, and it was when Orthodoxy became the state religion under Theodosius II that St. John Chrysostom ascended the patriarchal throne. And St. John saw how many problems there would be because of wealth in the Church. On the one hand, the Church gained access to the imperial revenues. They started building huge monumental churches in Jerusalem, in Constantinople, everywhere. On the other hand, St. John saw what this could lead to, how a man could crack and deteriorate under the influence of money. Therefore, he immediately got rid of the money and spent it on charity. And he advised others to do the same.

There was a hieromonk I knew, a blessed soul. I was serving in the altar with him one time, and I brought some money into the altar that some people had given for commemorations. He saw the money, and shouted: “Money in the altar! Get it out of here! What are you doing? This is a holy place!” Then I remembered about St. John Chrysostom and his character.

2:45 And sold their possessions and goods, and parted them to all men, as every man had need.

46 And they, continuing daily with one accord in the Temple…

They went to the Temple in Jerusalem every day to pray.

This raises the question of why they went to the Jerusalem Temple if the veil in the Temple had already been torn, remember? After all, this signified the uselessness of Jewish worship for Christians. All that was old had passed, and everything became new.

Yes, Christianity is a new religion. But the first Christianity was Judeo-Christian. The Apostles observed all the rules of the Law and at the same time served the Liturgy, preached the Gospel, and tried to live in a Christian manner. And this hybrid, Judeo-Christianity, existed until the destruction of the Temple in 70 AD. It ceased to exist as a phenomenon then, since it was associated precisely with Jerusalem. There was this Judeo-Christian community, headed by the Apostle James, the brother of the Lord. And after him, according to Tradition, Jude the brother of the Lord became the bishop of the Jerusalem community. And all these people were upholders of the Law.

When St. Paul came to Jerusalem, they told him: “Everyone here is a zealot of the Law”—that is, be careful. He was almost killed by the Jews themselves because of his supposed non-fulfillment of the Law. But St. Paul and the other Apostles went to the Jerusalem Temple. And the entire Christian community was Judeo-Christian. Although, if you look at our commentators—St. John Chrysostom, Blessed Theophylact, and others—they suggest that the Apostles understood that this wasn’t necessary, but they went to the Temple and kept the Law for the sake of the Jews, so as not to tempt them.

And every day they went to the Temple, in one accord, and broke bread in their homes. Again, this was an agape, the Eucharist, or a meal together with the Eucharist. They ate in joy and simplicity of heart. Joy and simplicity of heart were the characteristics of the first Christianity. As you can see, the penitential trait, so characteristic of our time, wasn’t so pronounced yet.

Now Orthodoxy is a repentant, ascetical religion. You might say it’s unlike the Christianity of the first century. The first century was a different time—we can’t recreate it. The way it is now is the way it should be. The Church has this kind of intuition. How does a Christian feel today? That initial Christian joy and simplicity of heart is still there now. But there’s been added weeping over sins, special labors to change our lives, some kind of pain associated with the confession of Christianity in this world, fighting with the passions, and the feeling of our own infirmity. These are the characteristics of our contemporary [Orthodox] Christianity.

For the first Christians, repentance was a powerful turning point once in a lifetime. Today, Protestants try to do this. It’s good, on the one hand, but times have changed. Man is healed from sin slowly and with difficulty. It can’t be all at the spur of the moment, quickly, instantly. And many Protestants feel it; the best of them. They feel over the years in their community that smiles, pot luck dinners, great enthusiasm, and even thorough study of the Bible don’t automatically make a Christian. They “rejoice” with their brothers in Christ, but they feel bad on the inside. And then when they hear that Orthodoxy has its teaching about the passions, they’re surprised. They don’t know anything about it at all. I know some pastors, and they don’t know the teachings about the passions. They don’t deal with this. They read the Bible. But how a man sins, what sobriety means, how to fight with this or that group of sins—they don’t know. When they get acquainted with our books, they’re amazed at the depth of Orthodox ascetic practice. Many come to Orthodoxy because they find true spirituality.

It’s impossible to reconstruct the spirit of the first Christianity—it was a different time, different people, a different era, a different mood, with different gifts of the Holy Spirit. Because the Holy Spirit also reveals Himself, gives an idea of Himself, testifies about Himself in various ways in the Church in different eras. And here, in Acts, everything is coming to a boil. This is the newborn Church, quite young. Joy in simplicity of heart, praising God and abiding in love with all people. That’s how good they were—good people and good Christians. But then the persecution began. Then they no longer abode in love with all people.