Part 1. Bulgarians and Russian Saints

Patriarch Neofit at the Liturgy at the Church of the Meeting of the Vladimir Icon of the Mother of God

Patriarch Neofit at the Liturgy at the Church of the Meeting of the Vladimir Icon of the Mother of God

—In May 2014, His Holiness Patriarch Neofit visited the Sretensky Theological Seminary. What were your impressions of his stay?

—All the monastery brethren and the seminary students rejoiced that His Holiness Patriarch Neofit paid a visit as part of the official delegation of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church in 2014. I was lucky enough to be there when we showed him the premises of the theological seminary. At some point I was even alone with the Patriarch when we were walking with him in the corridor along the classrooms and the library. He was completing his tour of the theological seminary and keenly interested in the way our seminarians studied, and what were their aspirations. I was struck by the fact that at that moment his face radiated incredible kindness. At the same time, he had an attentive and penetrating look. It was clear that nothing could be hidden from this man: based on many years of experience, he would immediately understand what was happening.

A few years after the visit of His Holiness Patriarch Neofit to Sretensky Monastery, Metropolitan Cyprian (Kazandzhiev) visited our monastery. He was accompanied by priests from the Stara Zagora Metropolis, who still remember and talk about their impressions of the Cathedral of the New Martyrs and Confessors of the Russian Orthodox Church at Sretensky Monastery, its frescoes, furnishings, lamps and acoustics. As I was personally told, they were struck by the beauty and splendor of the theological seminary, inspired by the fact that so many young people were studying there to become priests in the future.

—The faithful of the Metropolia of the Russian Orthodox Church in Bulgaria presented Sretensky Monastery with an icon of the Holy Hierarch Cyprian through you. Tell us more about that event.

—My visit to Bulgaria was a reciprocal gesture after the visit of His Holiness Patriarch Neofit to Sretensky Monastery. The meeting was organized by the rector of the Representation Church of the Russian Orthodox Church in Sofia, Archimandrite Vassian (Zmeyev). We celebrated a prayer service at the relics of St. Seraphim, who is much venerated by Bulgarians. The faithful of Bulgaria, as a token of their close spiritual bond with Sretensky Monastery, handed me an icon of St. Cyprian, which I recently brought to Sretensky Monastery.

I noted the fact that there were a lot of Bulgarians at the Representation Church of the Russian Orthodox Church in Sofia, consecrated under St. Nicholas II. Believers keep flocking to the grave and the memorial cross of St. Seraphim. There is an incessant influx of believers. People go even during working hours on weekdays.

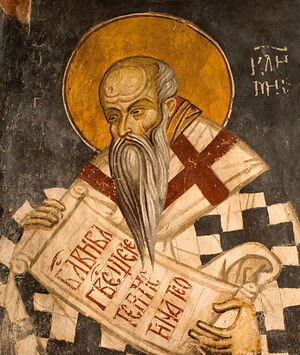

—Tell us how Sretensky Monastery is connected with the Holy Hierarch Cyprian.

—St. Cyprian was born around 1330 in the city of Veliko Tarnovo, the then capital of the Kingdom of Bulgaria. Between 1389 and 1406, with the title of Metropolitan of Kiev and All Rus’ he served in Moscow and was involved in the establishment of the Moscow Sretensky Monastery. According to the chronicles, on August 26, 1395, the cross procession, led by Metropolitan Cyprian, met the wonderworking icon of the Mother of God, brought from the city of Vladimir during the invasion of Rus’ by Asian oppressors. When the icon approached Moscow, the Turco-Mongol conqueror Tamerlane saw the Mother of God in a night vision and the next day ordered his soldiers to retreat from the Russian lands. The meeting of the Vladimir Icon, which was accompanied by the miraculous retreat of the invaders without a fight, took place at Kuchkovo Field, where later a church was set up in honor of the Vladimir Icon of the Most Holy Theotokos—the main church of Sretensky Monastery.

The Holy Hierarch Cyprian is still liturgically venerated at Sretensky Monastery as its founder. Thus, we commemorate him at every litiya during the Vigil. We speak about him during tours around the monastery. The seminary teachers speak at conferences with reports on the complications of that period of Russian history (the fourteenth and the fifteenth centuries), when St. Cyprian ruled the metropolia.

—What other Bulgarian saints are venerated at Sretensky Monastery, apart from St. Cyprian?

—Sretensky Monastery is not only connected with the Holy Hierarch Cyprian and the Venerable John of Rila, but also with St. Clement of Ohrid. Clement was one of the closest disciples of Sts. Cyril and Methodius, the Equal-to-the-Apostles. He founded schools in Devol and Glavinica, along with the Ohrid Literary School, which became one of the earliest cultural centers of the First Bulgarian Kingdom in the Balkans. In 893, he was unanimously elected the first Slavonic Bishop of Ohrid. There is an assumption that St. Clement of Ohrid created the Old Slavonic Cyrillic alphabet on the basis of the Greek alphabet. St. Clement is considered to be the embodiment of all ancient Slavic, and primarily Bulgarian, hymnography.

Since there is a master’s program at the Sretensky Theological Academy designed to train pastors with an in-depth knowledge of Church Slavonic, the Life of St. Clement of Ohrid, his hymns, as well as the literary heritage of his disciples in subsequent generations who brought the written language to Kievan Rus’, are the subject of our constant research. Our teachers and students are interested in ancient Bulgarian books, the nature of the Slavic language presented in them, and the dynamics of renewal of Slavic texts over the centuries.

St. Clement of Ohrid In addition to St. Clement of Ohrid, we also venerate the Holy Hierarch Seraphim (Sobolev). He lived in a tragic period that befell Russia in the first half of the twentieth century. The nature of his archpastoral ministry and the challenges of the time that St. Seraphim faced bring him closer to the New Martyrs and Confessors of the Russian Church venerated at Sretensky Monastery.

St. Clement of Ohrid In addition to St. Clement of Ohrid, we also venerate the Holy Hierarch Seraphim (Sobolev). He lived in a tragic period that befell Russia in the first half of the twentieth century. The nature of his archpastoral ministry and the challenges of the time that St. Seraphim faced bring him closer to the New Martyrs and Confessors of the Russian Church venerated at Sretensky Monastery.

Hieromartyr Hilarion (Troitsky), who was especially venerated at Sretensky Monastery, after graduating from the Moscow Theological Academy, made a trip to Mt. Athos. He traveled by train across the country from Moscow to Odessa, and then sailed on a steamer to Mt. Athos, making stops in the cities of Bulgaria and in Istanbul. Diaries with his travel notes are extant. In them he describes the customs of the Bulgarian clergy of the early twentieth century, comparing life in Bulgarian and Russian parishes. I recommend to everybody to read them. These diaries were included in the collected works of St. Hilarion, published by Sretensky Monastery.

I cannot help but mention another Bulgarian saint, whom I remember at every lecture on the Holy Scriptures of the New Testament. I mean Blessed Theophylact (c. 1050–1107), Archbishop of Ohrid in the Byzantine province of Bulgaria. The culmination of Theophylact’s literary activity was his commentaries on the books of the Old and the New Testaments. We use his commentaries on the Gospels in our classes on the Patristic approach to Biblical exegesis.

—Have students from Bulgaria come to visit us after the visit of His Holiness Patriarch Neofit to Sretensky Monastery?

—Traditionally, students from abroad study at the Sretensky Theological Academy. Since the day it was founded, the doors of our theological seminary have been open to everyone, regardless of nationality. Since the professors in our educational institution are outstanding pastors, along with specialists from leading universities of Moscow, up to thirty percent of our students are foreigners. These were mostly immigrants from Ukraine, Belarus and Moldova. Earlier, young men from Europe and Asia used to come every year as well.

After the visit of His Holiness Patriarch Neofit, we received a student from Bulgaria. Before the pandemic, he studied full-time and completed his studies online. We try to maintain friendly relations with him and with other alumni of the Sretensky Theological Academy. We are interested in what they are doing, and we constantly invite them to our joint seminary Liturgies in Moscow. He was not the first Bulgarian to study at the Sretensky theological Seminary, and not the last. We currently have another Bulgarian student, born in Ismail. We hope that in the future more Bulgarians will continue to come to us. It is easy for them to study here because our languages are closely related—especially the liturgical language.

—Father, tell us how you saw Bulgaria from inside during your trip.

—Bulgaria has its own problems with unemployment, poor living conditions, etc. In terms of living standards, Bulgaria is neither Germany nor France. Even current refugees just briefly arrive in the country to move further northwest. It has a very unstable economy and political system—for the past two years there has been a purely nominal government there, which is why important issues are not being resolved promptly.

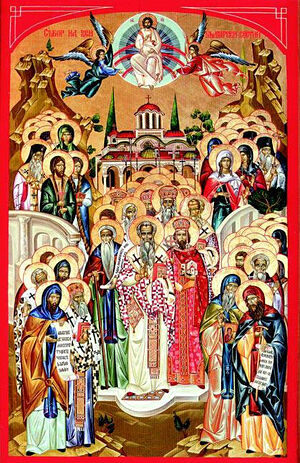

Synaxis of the Saints of Bulgaria I did not notice any particular piety among Bulgarians. There are few people in churches on a regular basis, which is probably the result of the Communist legacy. There is a dramatic shortage of monastics. Even in such places as Rila Monastery, one of the largest and most beautiful in the Balkans, there are serious problems with monastics. As a rule, two or three people of advanced age live there, and they simply sustain life, some status at the monastery. The monastery buildings are rented by secular people and organizations whose level of integration into Church life leaves much to be desired.

Synaxis of the Saints of Bulgaria I did not notice any particular piety among Bulgarians. There are few people in churches on a regular basis, which is probably the result of the Communist legacy. There is a dramatic shortage of monastics. Even in such places as Rila Monastery, one of the largest and most beautiful in the Balkans, there are serious problems with monastics. As a rule, two or three people of advanced age live there, and they simply sustain life, some status at the monastery. The monastery buildings are rented by secular people and organizations whose level of integration into Church life leaves much to be desired.

But there are also positive aspects: the monastics whom we met on the way have very sincere faith; they live modest and simple lives, yet in greatness of spirit. And people who go to church treasure their faith very much. Priests are extremely welcoming and friendly. And there is an abundance of holy places in Bulgaria. There is much for the Orthodox pilgrim to see.

All the churches of the Russian Orthodox Church in Bulgaria are very solid, with their recognizable ancient Russian architecture. The Russian presence here is very much alive: with “our” distinctive iconostases and rich decorations. These are islands of Russia in Bulgaria.

—What are the differences between the Bulgarian and the Russian liturgical traditions?

—In part, such a tiny number of parishioners in churches is because in the Bulgarian tradition, parishioners are allowed to receive Communion only once a year or four times a year. So the priest serves the Liturgy daily or three times a week and receives Communion, while the faithful stand at the closed doors and do not have such an opportunity.

This phenomenon has an explanation: traditionally in this way parishioners are taught a very reverent attitude towards the sacrament of the Eucharist. But when Metropolitan Tikhon (Shevkunov) met His Holiness Patriarch Neofit and asked him about the appropriateness of such infrequent Communion, he received an answer about the well-established Bulgarian tradition.