Nun Maria (Balan) from Agapia Monastery is the sister of the famous Archimandrite Ioanichie (Balan) of Sihăstria Monastery, the great spiritual father, hagiologist of Romanian saints, and compiler of the landmark Romanian Patericon. They were connected not only by blood, but also by strong love for Christ, to Whom they both devoted their lives.

She was born in the village of Stănița in Neamț County, the ninth child in a simple peasant family. And her brother, the famous confessor Ionichie (Balan), was the second child and first boy. There was a difference of nineteen years between them, but it didn’t prevent them from loving each other as only true brothers and sisters can. Mother Maria and Fr. Ioanchie lived in monasteries located near each other, across a mountain pass, on that patch at the foot of the Neamț Mountains that is known as the Romanian Athos. Most of the largest monasteries in the country are gathered there—Secu, Sihăstria, Sihla, Agapia, Văratec—over which both ancient and newly revealed saints awaiting canonization stand guard.1

The dusk was thickening when I met her—a dusk that wrapped the story of her life in gold, as if pouring out from the other world.

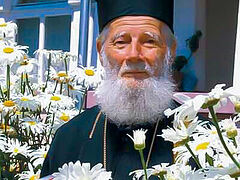

Brother and sister, Mother Maria and Archimandrite Ioanichie

Brother and sister, Mother Maria and Archimandrite Ioanichie

“The communist period was hard for the faith, but at the same time wondrous, because we had these great confessors with us. Holy people… Do you know what happiness it is to follow in the footsteps of the saints?”

Beginning

Archimandrites Cleopa (Ilie) and Ioanichie (Balan), c. 1952-1954 “Which one of them is my brother?” she wondered. Two monks stood before her, dressed in long, black riassas and white sheepskin vests. One was young, thirty years old, with fair hair and sky-blue eyes—this was Fr. Ioanichie (Balan); the other was a bit older, a man in the prime of his life, just over forty—Fr. Cleopa (Ilie).

Archimandrites Cleopa (Ilie) and Ioanichie (Balan), c. 1952-1954 “Which one of them is my brother?” she wondered. Two monks stood before her, dressed in long, black riassas and white sheepskin vests. One was young, thirty years old, with fair hair and sky-blue eyes—this was Fr. Ioanichie (Balan); the other was a bit older, a man in the prime of his life, just over forty—Fr. Cleopa (Ilie).

And only when the whole village flooded to their house to see them did Maria realize which one was her brother. He wasn’t an ordinary man. He was a monk, and not a simple one, but from Sihăstria Monastery, where Fr. Cleopa (Ilie) himself was the abbot, who the people already loved and revered as a saint by that time.

That’s how it was. When he preached in the village church, everyone wept. Even if you were made of stone, his words couldn’t fail to touch the depths of your soul—fiery words emanating from otherworldly realms and gathered in his heart by the power of prayer.

The whole village passed through their house then—a continuous string of people wanting to talk with these monks, to ask them for advice and often to assuage their sorrows with the power of their blessing.

“Times were very tough. Full-scale collectivization hadn’t begun yet, but every peasant had to give the state the majority of what they produced. If anyone couldn’t, then they’d go to his house and confiscate everything he had. And people were looking not just for comfort from Fr. Cleopa and my brother, but also advice. They didn’t know what to do in the face of such a ruthless dictatorship that only caused fear.

“I remember that before he left, Fr. Ioanichie left us a suitcase full of his manuscripts. He thought persecution was about to begin and he would be arrested. He escaped arrest, but not persecution.”

Brotherly love

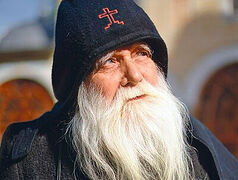

Archimandrite Ioanichie Fr. Ioanichie loved and cared for his sister her whole life. In his old age, he would tell his disciple, a married priest:

Archimandrite Ioanichie Fr. Ioanichie loved and cared for his sister her whole life. In his old age, he would tell his disciple, a married priest:

“Father, we monks partake of every one of God’s blessings, save one—carrying our own children in our arms. God has granted this great joy only to you all in the world. But know that I partook of this a little bit as well, because I held my sister Maria in my arms. When I left for the monastery, I was nineteen, and she was two months old. I hugged her last and I’ve always lived with the memory of her.”

As the years passed, the girl grew up, but her brother continued to watch over her from his monastery seclusion, and not just with prayers.

“Father really loved me. I remember, he would tell our mother: ‘I don’t know why, but she’s very precious to me.’ And you know, he was always watching out for me. Once I was quite sick with tuberculosis, and I got a letter from him while I was in the hospital, covered with the stains of his tears… He was very worried about my health. I could always sense his very tender, very sensitive soul.”

A capital of saints

Agapia Monastery, where Mother Maria labors

Agapia Monastery, where Mother Maria labors

Maria was a student, and when Fr. Ioanichie would come to visit her, they would wander around the capital. Every door opened before them; they were received with love everywhere. In those dark years, there was an invisible network of spiritual authorities in Bucharest, circulating the love of God. The dictatorship notwithstanding, in churches closed for subsequent demolition, in frozen apartments, and tiny monastic cells, you could meet with priests such as Dumitru Stăniloae, Constantin Galeriu, Sofian Boghiu, Ilarion Agratu, and Benedict Ghiuş. Mother Maria entered into these circles that burned with faith and represented spiritual resistance to the dictatorship, through Fr. Ioanichie—a highly revered and scholarly monk, much loved by everyone.

“Everyone was very hospitable, full of love; I could go to their homes or monasteries at any time. I would go to Cernica Monastery to Fr. Benedict Ghiuş for some time every day, because I was helping him with the publication of the Prologues. I was simply in love with Cernica, and when I would walk along the alley leading to the church, I always felt extremely happy. I really love St. Calinic.2 He’s always so warm and loving! After venerating his relics in the church, I’d go to Fr. Benedict’s cell.

“Do you know what he was like? A saint! That’s how I always perceived him. It’s hard to explain why. It can only be felt, not explained. He was very erudite, richly gifted from God: He sang beautifully, he was a talented writer, and an unrivaled preacher. He was completely immersed in himself, and at the same time a very friendly person; a delicate nature.

“He was quite silent. Sometimes when I was alone with him, we would finish working on the Prologues and he would simply fall silent, immersed in the prayer of the heart. Usually in a situation like this, where a person doesn’t talk to you for such a long time, you feel awkward, unnatural, and a lump forms in your throat. But with Fr. Benedict, I could spend an hour not saying anything, and we didn’t notice how time flew, because there was grace all around him.

Persecution

Fr. Cleopa (Ilie) and Fr. Ioanichie (Balan) were too strong, too pure, and their words were too beloved by the people for the security services to leave them together, so they were separated. Fr. Ioanichie was driven out of Sihăstria Monastery and sent to Bistrița Monastery near the town of Piatra Neamț so it would be easier for informers to follow him. Fr. Justin (Pârvu), who had seven years of the harshest imprisonment behind him, was also sent there. Without realizing it, the communists had done the work of God. There, in Bistrița, Fr. Ioanichie continued working on his books, with which he saved from oblivion and immortalized all the great Romanian saints.

“As soon as he would leave the monastery, the security officers would enter his cell and rummage through everything. One time they took one of his manuscripts, and it was extremely difficult to get them to return it, even though there was nothing political in it. He wasn’t involved in politics at all, but still, his homilies, which the people really loved, were a slap in the face of the regime. So his transfer to Bistrița was from God, and Father was greatly loved there. People would come to him from the city of Piatra Neamț and all the surrounding villages. They also came to Fr. Justin (Pârvu), who was simply drowning in a crowd of people in Bistrița. He didn’t even have time to go to church for the Liturgy, he was so sought after by the people. They really loved him too, because he was very meek and had endured suffering in prison.

A book from the east

Compiler of the Romanian Patericon, Archimandrite Ioanichie (Balan) From childhood, she would go see her brother Fr. Ioanichie at Sihăstria Monastery, but her calling to monasticism didn’t mature immediately:

Compiler of the Romanian Patericon, Archimandrite Ioanichie (Balan) From childhood, she would go see her brother Fr. Ioanichie at Sihăstria Monastery, but her calling to monasticism didn’t mature immediately:

“I remember one time Father took me to the tiny monastery library. ‘Look, he said, ‘I arranged all the sacred books from the East, and all the rest from the West. Pick one you’d like to read!’ I looked at the titles and told him: ‘I’d like one from the West!’ ‘No, my sister, I implore you, take a sacred book, from the East. I give you the obedience of reading the Acts of the Apostles.’

“And there was no electricity at Sihăstria at that time. We read by lamplight, and it was so beautiful! They sang quietly on the kliros. It wasn’t Byzantine chant, but a very simple melodic line. It was essentially prayer-chanting, where the music receded into the background and love for the Lord remained in the foreground.

“Thus I learned what a monastery is. In 1968, I was helping Nun Agafia, my second cousin, at Văratec Monastery, when suddenly she said to me: ‘You know Fr. Ioanichie would be glad if you joined a monastery.’ It was as though the vault of the heavens came crashing down on me! I started praying, walking circles around the church, and came to a decision. I was in my second year of college then, and I liked to see things through to the end. So I decided I would finish school first (at the Academy of Economic Research).

Văratec Monastery, Church of the Dormition of the Most Holy Theotokos. Photo: Shutterstock

Văratec Monastery, Church of the Dormition of the Most Holy Theotokos. Photo: Shutterstock

“And when I finished, my brother Fr. Ioanichie decided to test me and asked me to wait a bit. I think Father wanted to see my decisiveness, and wanted to wait for the wave of persecution that came crashing down on the monasteries after Decree No. 410 in 1959, when all the monks were expelled from their monasteries, to pass. The decree wasn’t canceled, and although the monks started returning to their monasteries, they did so illegally, trying to gain a foothold in the monasteries under any pretext, as museum or trade shop employees.

The prayer of Elder Paisie (Olaru)

Hieroschemamonk Paisie (Olaru) “Do you still have joy?”—this is what Fr. Ioanichie asked her every time they saw each other. He knew that nuns feel extremely happy in the first years after they join a monastery. Grace from above overflows the heart of the novice and helps her pass through any test unscathed. Mother Maria very clearly remembers these years, when God carried her in His arms”

Hieroschemamonk Paisie (Olaru) “Do you still have joy?”—this is what Fr. Ioanichie asked her every time they saw each other. He knew that nuns feel extremely happy in the first years after they join a monastery. Grace from above overflows the heart of the novice and helps her pass through any test unscathed. Mother Maria very clearly remembers these years, when God carried her in His arms”

“When you have a calling to monasticism from Christ, you don’t walk to a monastery—you run! This is the grace of God, great grace. At first it envelops you, then it weakens and trials come to teach you humility. For me, the joy of joining the monastery was immense. I wanted to embrace all the sisters, I was so happy! There was an abyss of love between us. We’d be working in the field, and I’d fall behind, when suddenly I’d see a couple of nuns in front of me who had finished digging their row and had come to mine, hurrying to dig it up too. Or when it was snowing, we’d get up at midnight and go to the older nuns to shovel the snow around their huts. It was wonderful in those years! And we had a special abbess, dear Eustochia (Ciocanu), a former student of Fr. Stăniloae. I loved her very much.”

Mother Maria chose Agapia Monastery, where she still labors today, to be closer to Elder Paisie (Olaru) who was laboring at Sihla Skete at that time. Thousands of pilgrims clambered along the paths of the Neamț Mountains to get to the tiny cell of the holy confessor.

“When I entered the monastery, I asked the abbess to allow me to go see Fr. Paisie at least once a month. I’d go see him at night sometimes, because we had work during the day. There were only old huts in Sihla at that time, each one lit by a single lamp. Father lived up above, in a small cell under a rock. He was kind, like a mother! During Confession, you could bury your head in his lap,” Mother Maria says weeping.

“I had always wanted to have a spiritual father like him. He was very kind. Very kind! He pastored us with great love. At midnight, he would gather us under his stole like a mother hen, and read an amazing prayer over us that he had composed himself: ‘Bless, O Lord, their labors, their homes, their bread, their children, their lives, and mercifully grant them a good end, and in the next world, on the Day of Judgment, grant them a corner of Paradise, for blessed art Thou unto the ages of ages.’ And at the end, he’d always wish: ‘May we meet at the gates of Paradise!’

“He was simply priceless! He always had little poems that made us smile. As we climbed the mountain, he’d say, ‘Let’s go to Paradise, Paradise, Paradise, on a two-horse cart!’3 Then he explained that the two horses are the body and the soul, and the cart carries our deeds.

“We young nuns would tease each other a bit, but only I really suffered from it; it can be like this in a monastery, because we come from the world with ambitions that are hard to give up. And Fr. Paisie taught me to see all the nuns as better than me, to make me humble. He’d tell me to go to church and say in front of an icon: ‘I’m guilty of everything!’ But he said it with such love! He corrected us with great love, to humble us, but he understood us too.

Fr. Ioanichie’s departure

After Fr. Cleopa departed to God, on December 2, 1998, Fr. Ioanichie started telling his disciples that he’d like to retire into silence. He gave his whole life to Christ, going around the whole country searching for stories about the ancient saints. His books have raised an entire generation; they’ve been read by everyone, from the simplest believers to hierarchs. He fulfilled his mission, and now, at seventy years of age, he was looking for some rest in prayer; he wanted peace and quiet, which he needed his whole life.

“Fr. Ioanichie was of a contemplative nature. He really loved to pray. In his journal, he wrote that after leaving Matins at 2 AM, he’d go to the cemetery to pray at the graves of the great Sihăstria elders.”

Perpetual lampadas at Sihăstria

Perpetual lampadas at Sihăstria

In the end, God fulfilled his thirst for solitude by sending him a serious illness. And in his last years, until he took up his abode in Heaven in 2007, he knew only one road: from his cell to church and back, and he was always led by his disciples.

“Stay here, you’re like a mother for me!” he’d always say when she’d go to Sihăstria.

And in the end, she stayed.

“My brother was very perceptive; he had a very sensitive soul, the soul of a poet. He’d weep when I’d read Eminescu’s poems to him in his final years. I was with him when he departed to the Lord on the night of November 22. He had fallen into a coma ten days prior, and a real pilgrimage began to his bedside. A procession of faithful, priests, monastics, and hierarchs came to see him.

“On November 21, at eight in the evening, I was sitting next to him, reading the Psalter. He was breathing very hard, but when I got to Psalm 119, I noticed that he started breathing normally. Then his breathing became weaker and weaker, and at 2:20 AM, it died off. It was snowing outside the window… He died peacefully.

“Sometimes I see him in my dreams. Once I saw him in his vestments—he blessed me and disappeared. He was so joyful. Very joyful! And I woke up happy, in seventh heaven.

“He was very dear to me! And it wasn’t just him I felt attached to like a blood relation, but also other elders of the last century. They were all real fathers! When I was with them, it didn’t even feel like I was living in an era of dictatorship. I was so happy!

“I feel that they’re still talking to us. I always think about them. They’ll remain an ideal for me until I die. I always think: What would they say, what would they do if they were in my spot right now? And with this thought, it’s easy for me to make a decision to keep the true path to God.”