By decision of the Holy Synod of the Romanian Orthodox Church on July 11–12, 2024, sixteen God-pleasers who shone forth in the twentieth century were glorified among the saints. Among them is Hieroschemamonk Paisie (Olaru; 1897–1990), the spiritual father of Sihăstria Monastery, who from now on will be known as St. Paisie of Sihăstria, whose feast will be celebrated on December 2 (new style).

“May we see each other at the gates of Paradise!”

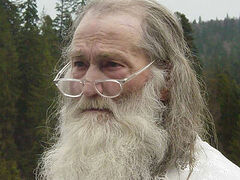

Elder Paisie of Sihăstria He lived for ninety-three years, almost seventy of which were in a monastery. During this long life, a huge number of people passed under his stole. He was the spiritual father of both major Church figures and ordinary peasants, for Fr. Paisie (Olaru) had the right word for everyone.

Elder Paisie of Sihăstria He lived for ninety-three years, almost seventy of which were in a monastery. During this long life, a huge number of people passed under his stole. He was the spiritual father of both major Church figures and ordinary peasants, for Fr. Paisie (Olaru) had the right word for everyone.

He received anyone who knocked on the door of his cell—always, at any time. He would hear confessions without stopping, for several days in a row, day and night. No one knew when he slept or ate—it seemed to everyone that he didn’t have time for such earthly activities. Everyone knew him that way—standing at the analogion in his stole and confessing someone, as though he was simply born so old and wise. Hundreds of thousands of people entrusted their sorrows to his all-embracing and kind heart and departed from the Elder happy and uplifted.

He wasn’t a great scribe. He only went to school for three years, and anyways, it was impossible to learn this bottomless wisdom from books. It flowed from above. And that’s why everyone sought him out—both the simple people and the refined intelligentsia. All obediently bowed their heads under his stole, and Father blessed them with the words: “May God grant you a corner of Paradise!”

Prayers for his disciples poured out unceasingly from his heart, full of grace:

“Bless, O Lord, their house and their table, their life and their joy. May we see each other at the gates of Paradise!”

Among all the spiritual figures who have made this dark twentieth century brighter he stands first—our Confessor.

Guide of Fr. Cleopa

The fall of 1935. United Romania was as big as ever.1 Its people were strong and determined; they believed in their destiny. That fall, Fr. Cleopa, then still the young soldier Constantin, arrived for a short visit at Cozancea Skete, not far from his native village. Fr. Paisie (Olaru) had been laboring there for about fourteen years already. He was a humble hermit monk then, who built himself a cell in a clearing not far from the skete and labored there, contemplating the beauty of nature and immersing himself in the love of God. He was thirty-eight and he had been pastoring Constantin and his brothers since they were children, when they grazed their father’s sheep near his cell. A strong spiritual bond developed between him and the future great Sihăstria abbot Fr. Cleopa, although Fr. Paisie wasn’t a priest then and couldn’t confess the young shepherd boy who came to him only for advice and enlightenment:

“Fr. Paisie raised us and was a guide and spiritual father for my four brothers and I there in Cozancea. And we all went to the monastery! Without his holiness, perhaps none of us would have become monks.”

Even in those years, the hesychast who lived in silence in the clearings near the Cozancea skete was surrounded by a mystery that would become obvious to all when he reached maturity. This was the mystery of a spiritual guide and ruler of souls, a science that doesn’t necessarily require the grace of priesthood, but absolutely requires the grace of wisdom and the fire of Divine love. People, especially those thirsting for prayer, sense such elders unmistakably.

Even in those years, the hesychast who lived in silence in the clearings near the Cozancea skete was surrounded by a mystery that would become obvious to all when he reached maturity. This was the mystery of a spiritual guide and ruler of souls, a science that doesn’t necessarily require the grace of priesthood, but absolutely requires the grace of wisdom and the fire of Divine love. People, especially those thirsting for prayer, sense such elders unmistakably.

Fr. Paisie exhorted Constantin to become a monk and labor in the same place, but he told him he wanted to go to Sihăstria, where two of his brothers were already monks. Then the wise monk suggested that he take this oath:

“Lord, if it be Your will, bless us to be together both in this age and in the age to come. And if my brother dies before me, let me stand at his bedside; but if I die first, then let him stand at mine!”

They sealed it with the word “Amen,” and Constantin returned to his regiment. They didn’t even know that they had laid the foundation of the strongest spiritual friendship that our monasticism would know in the twentieth century.

Peter the Merciful

When he was born in 1897, he was named Peter, like the Apostle. And he, like the Apostle, was to turn many people’s hearts to God, filling them to overflowing with his simple and fervent faith. He grew up with eight brothers and sisters in the fragrant rhythm of morning and evening prayers and the Sunday scent of incense. His parents were simple but strong believers, just like their tiny Botoșani village.

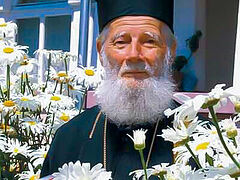

Elders Paisie and Cleopa In his old age, Fr. Paisie said that his father, Ion, who served as a forester on a local nobleman’s land, spent most of his life in dugouts that he dug himself, dwelling in the solitude of dense forests. He prayed simply and aloud, so that he could be heard from afar.

Elders Paisie and Cleopa In his old age, Fr. Paisie said that his father, Ion, who served as a forester on a local nobleman’s land, spent most of his life in dugouts that he dug himself, dwelling in the solitude of dense forests. He prayed simply and aloud, so that he could be heard from afar.

“My mama,” Father said, “was very compassionate, and her songs were often mixed with lamentations.”

She was a woman of great pain of heart and would often weep for her sons who went to the front. When the First World War began, Peter was seventeen. Two of his brothers were already drafted, and their mother could find no peace thinking about them. Every day, a funeral procession with one of the soldiers from their village who had died in battle would slowly drag past the Olarus’ gates.

“Mama wailed for all of them like they were her relatives: ‘My dears, mama’s children, your mama will never see you again.’ And I would wipe her tears and say: ‘Don’t cry, mama, don’t cry.’ And I myself would cry out of pity for her. My dear mama! There’s nothing on earth more precious than the name of mother!”

Tormented by anxiety for her sons, exhausted by so many losses in their large village family, Ekaterina fell ill. She died young.

When her coffin was being carried out of their gates, one of her sons who had gone to the front hurried to meet them. He was unharmed. He deserted his unit in order to see his mother one last time. It was too much for Peter:

“I cried so much from inconsolable pain that I thought I would fall into her grave.”

Peter only finished three grades in school, but he received awards at the end of each school year. They gave him a crown to wear. One teacher gave him a book of the lives of the saints, and so, reading about their valiant labors, he decided to become a monk. He clung to the Church with all his soul, and over time, it came to take the place of his mother in his heart, after she departed so early to God.

A monk from the Cozancea forest

Peter didn’t go far. He was used to the patriarchal atmosphere of his native village and didn’t want to leave it. He changed his way of life, but not the place, when in the fall of 1921 he left for Cozancea Skete—a two-hour walk from his parents’ house.

There his compassionate heart quickly found a suitable obedience: taking care of the elderly monks. He would take them food, clean their cells, and watch over them when they were sick. And when they died, he would dig their graves himself and pray for them. Thus, his heart opened up to love all people. He had room for both the good and the bad—after all, not everyone he cared for was a saint. But he covered all their shortcomings with pity and understanding. One of the old men would tell him:

“Paisie, you’re both a father and a mother for me!”

After so many years of monasticism, his soul learned to swim in the pure waters of prayer. In the woods, he would remain vigilant for hours, learning the art of restraining his thoughts and of the prayer of the heart. He asked the abbot to bless him to go into the desert, because his soul yearned for the depths of God. But he wasn’t given a blessing, because the brotherhood really needed him. But he was eventually allowed to build a cell in the forest clearing. There he counseled Fr. Cleopa, then still a boy, grazing his father’s sheep nearby, and there he tasted the fruits of hermeticism. However, this thirst for solitude would remain in his soul throughout his life, because he always had to combine love for God with love for man.

His first disciple

It was the spring of 1932. The winter had not yet shed all the sheepskin coats, and the islands of snow were growing white among the delicate greenery of barely sprouted grass. It was time for Vespers, when day turns to night, and the monks return from various obediences to the silence of the church. A strange-looking old man came through the door of Cozancea Skete. He had long strands of gray hair and a white beard, and no shoes on his feet. He had been walking through the snow and mud for several hours, having taken off his bast shoes so they wouldn’t get dirty. Amazed by the sight, Fr. Paisie invited him into his cell.

Fr. Paisie at Sihla His name was George. He had been a shepherd for as long as he could remember and had been sleeping on the bare ground for just as long. He had never been married and never even tried to acquire any property. He was more of a forest dweller and friend of wild beasts than he was a villager. He was a shepherd with faith as gigantic as the mountains he roamed. After a few days, he moved to live with Fr. Paisie in his cell and became his disciple. He was the first and perhaps the most diligent.

Fr. Paisie at Sihla His name was George. He had been a shepherd for as long as he could remember and had been sleeping on the bare ground for just as long. He had never been married and never even tried to acquire any property. He was more of a forest dweller and friend of wild beasts than he was a villager. He was a shepherd with faith as gigantic as the mountains he roamed. After a few days, he moved to live with Fr. Paisie in his cell and became his disciple. He was the first and perhaps the most diligent.

“Poor man, he made bows from the waist and prostrations all the time. Once I thought about counting how many he could do. I counted to 800 and fell asleep,” Fr. Paisie said about George.

The destinies of these two ascetics were Divinely intertwined. The young monk told the old man about the monastic rules, and in return received a living example of a soul tempered in asceticism, unshakable in prayer and fasting. Brother George wasn’t just a pious shepherd. He was a saint.

“As soon as he heard something about God, the Most Holy Theotokos, or the saints, he would begin to shed floods of tears. I loved him; I couldn’t get enough of his words!”

Having crossed the threshold of eighty, Grandpa George got sick and was tonsured a monk with the name Gennady. When he felt like he was dying, he asked to be carried out of the cell so he could look up to Heaven, under the cover of which he had spent his whole life. They laid him right on the grass. The old man turned his face to the east, said a prayer, and died. This was the autumn of 1948.

After his companion departed to the Lord, Fr. Paisie also left the skete. He had wished to go be with Fr. Cleopa at Sihăstria Monastery for many years, but the abbot didn’t bless it. But now he didn’t need it (since he himself was the abbot) and he left. He was fifty-one then and had been ordained a hieromonk just a year prior. Nevertheless, there, in Sihăstria, streams of people would flock to him for Confession.

Sihăstria

At Sihăstria, Fr. Paisie was given a cell right by the altar. He had just one obedience—to confess the brethren and pilgrims. Having served as a priest for just a year, he had to give advice to monks with rich experience about how to be perfected, because he, the humble Paisie, a hermit from the forests of Cozancea, had something more. He had unrestrained love hidden in his heart, which he wanted to share with everyone who needed it. It wasn’t years in the priesthood that made him the most sought-after confessor, but rather the grace that seeped through every pore of his soul.

The brother’s residence at Sihăstria. Photo: filaretuous.livejournal.com

The brother’s residence at Sihăstria. Photo: filaretuous.livejournal.com

This mercy was felt by the soul of every believer. And to acquire it, they were ready to travel thousands of miles and wait for hours at Father’s door, begging not for bread but for words, as if for alms—words that were living, descending from Heaven. And Father gave them to them.

He was called a hermit, although he lived in a big monastery and was surrounded by hundreds of pilgrims every day.

In Sihăstria, Fr. Paisie poured out his rich talents before the people for the first time. And he didn’t feel sorry for himself.

“He confessed day and night, both monks and laymen. He didn’t even have time to eat. He ate and labored in secret. No one knew how much he prayed and how; how much he fasted and how; what he did in general and what mystery he concealed within himself. He was full of humility, meekness, and love. He wept with the weeping and rejoiced with the rejoicing,” remembered Father Cleopa. “I confessed to him, and he to me. I was so grateful to God for bringing him to Sihăstria.”

The years in which this spiritual depth was born were not easy ones. Soviet tanks were just then establishing a harsh and godless regime in Romania. And yet, in the midst of persecution that was about to break out, God initiated spiritual movements whose power, depth, and beauty we admire today. Such were Frs. Paisie and Cleopa in Sihăstria, Arsenie (Boca) in Sâmbăta de Sus, Constantin Galeriu in Ploiești, and the members of the Burning Bush group in Bucharest.

The regime destroyed these movements after a few years. It cruelly tried to wipe them off the face of the earth forever. The members of the Burning Bush movement wound up in prison: Frs. Constantin Galeriu and Arsenie (Boca)—on the construction of the Danube-Black Sea Canal, and Fr. Cleopa was persecuted by the Securitate and he was forced to flee to the mountains several times. He was in complete solitude there, immersed in prayer for himself and for the whole world.

Fr. Paisie was miraculously spared.2 For forty years he didn’t leave the analogion, and the regime didn’t touch him. All this time he was torn between Sihăstria and the Sihla hermitage, between monastery and hermetic life. But whether he was in the monastery, in his little chamber under the shadow of the altar, or in the mountains in a cell nestled against a rock, his door was always open.

Sihăstria Monastery. Photo: ziarulumina.ro

Sihăstria Monastery. Photo: ziarulumina.ro

Sihla

Sihla is about an hour’s walk from Sihăstria, but the path goes through difficult vertical cliffs and leads into another world. When Fr. Paisie first climbed up there, the skete was like an eagle’s nest, and in the impenetrable forests around it were scattered the huts of many hermits. The skete, rising up to the rocky cliffs under whose shelter St. Theodora labored in complete solitude, was more of a refuge for hesychasts than a brotherhood.

Near Sihla. Photo: sihla.mmb.ro

Near Sihla. Photo: sihla.mmb.ro

Fr. Paisie chose a cell up above, a bit farther from the church, under the shadow of a rock. From there he saw the first rays of the sun and was the first to plunge into the darkness of night. He could give glory to God for the new day and retire when the last streak of light hid behind the crest of the mountain. Silence, undisturbed by anyone, reigned in these places, blessed by the prayers of hundreds of hermits who labored in the surrounding forests.

Fr. Paisie’s cell at the Sihla Skete. Photo: dzen.ru

Fr. Paisie’s cell at the Sihla Skete. Photo: dzen.ru

There were few inhabitants at the Sihla Skete. But they were monks who loved silence and prolonged prayer, and this atmosphere was ideal for Fr. Paisie. His life flowed in the rhythm of nighttime services, secret vigils in his cell, and receiving all the pilgrims who came to him for counsel, whenever necessary.

If he had a break, which happened very rarely, he would work in the tiny garden that he had planted himself. No one ever found him sitting around doing nothing. Not even for a minute. All this time he assisted in the inner rebirth of the faithful, including outstanding figures of Romanian cultural life.

To be continued…