Source: Orthodox Arts Journal

In recent months, discussions posted on various blogs and other social media have brought to light the ongoing quest of Orthodox church musicians in North America to define more clearly their vocation and sense of professional identity. A good deal of discussion has focused on the desirability and necessity of establishing an Orthodox choir school. New educational initiatives for continuing education of parish choir directors and singers have surfaced, taking their place alongside existing ones. Clearly, there is a sense of ferment, even of urgency, in this realm.

While such activity is a welcome novelty in North America, where Orthodoxy is still, even after 200+ years, a relatively new phenomenon, and is only beginning to make serious educational, vocational and missionary efforts in certain areas, it may be more surprising to learn that some of the same issues and challenges also exist in a traditionally Orthodox country such as Russia, due in large measure the 75 years of Soviet Communist persecution which the Orthodox Church experienced there. The following interview with Boris Ivanovich Kulikov, who was one of the most prominent choral conductors and educators of the Soviet Era, and is now a practicing Orthodox believer, offers valuable insights into some of the struggles that church music in Russia has undergone and continues to undergo as it strives to resurrect and preserve that fragile and precious thing called “tradition.”

To the various topics touched upon in the interview one should add that just three years ago the Moscow Conservatory took an important step to revive instruction in the field of Orthodox church music, hiring one of its own graduates, Vladimir Gorbik, to the choral conducting faculty, thus effectively restoring the Conservatory’s link to Orthodox sacred music that had been severed with the closing of the Moscow Synodal School of Church Singing in 1918.

An Interview with Boris Kulikov

The Moscow Conservatory has succeeded in preserving the finest achievements of choral church singing in Russia. In the following interview, Boris Ivanovich Kulikov, Honored Artist of the Russian Federated Republic (RSFSR) and a Professor of Choral Conducting, who for sixteen years served as Rector of the Moscow Conservatory, speaks about the relationship between singing and church services, as well as the continuity of the musical tradition at the Moscow Conservatory. Previously, he served as Assistant Conductor and Choirmaster of the USSR State Choir under the direction of Alexander Sveshnikov, and Deputy Artistic Director of the Alexandrov Soviet Red Army Chorus. Now in retirement, Mr. Kulikov is a parishioner at the Moscow Representation Church of the Trinity-Sergius Lavra.

Boris Ivanovich Kulicov

Boris Ivanovich Kulicov

Singing is in fact the basis for religiosity. After all, what is singing? It is unity, a kind of unity that today we cannot even fathom: for us, choral singing is the highest manifestation and integration of vocal expression and mankind’s spiritual essence; but in the days of the early Christians in the catacombs to manifest unity in this fashion was a matter of life and death.

– Do you think that the adoption of polyphony has distorted spiritual singing?

I would not say so. Alexei Lvov (1798–1870) and Dmitry Bortniansky (1751–1825) were great, brilliantly educated composers. True, they were trained abroad, many—in Italy, because we did not have a tradition of music education back then. But what Russia did have was a strong tradition of patronage of the arts. Russian emperors viewed music seriously, as part of their prestige, and they treated it with incredible care. Italian musicians performed very readily in our country because they were paid well. Verdi, for example, was paid quite well for La forza del destino [an opera specifically composed for production at the Bolshoi Kamenny Theater in St. Petersburg –Ed.]

– In your opinion, is it possible to distinguish between the sound of secular choral singing and church singing?

Of course. Everyone sings Rachmaninoff’s Vigil these days, if not in its entirety, then as individual movements. On the surface, the singing seems to be beautiful. But in fact, it is like a painting that’s been defaced. The innermost sanctity of the singing has been violated. One can recognize this by certain telltale emotional signs, a certain emotional context. If the persons [singing] do not have a religious framework, it is not merely noticeable, it’s criminally noticeable.

– Why, in your opinion, does this happen? What exposes a secular person?

First of all, a secular forte and a forte that comes from a person’s innermost being are two entirely different things. Spiritual singing possesses the elements of a sacrament. Any church choir director, even one who is self-taught, is familiar with this mystery, which he hears and can communicate to his singers. But professionalism and tradition are no less important.

In the days when the Moscow Synodal School of Church Singing existed, choral singing was developed to the level of perfection, tried and tested by centuries of experience. The teachers who taught in the Synodal School were worthy people, great musicians and scholars—Alexander Kastalsky (1856–1926), Vasily Sergeyevich Orlov (1856–1907), and others. Stepan Smolensky (1848–1909) was the school’s fine administrative director. He was both a scholar and a composer—it is to his memory, incidentally, that Rachmaninoff dedicated his All-Night Vigil. Smolensky had taken Rachmaninoff under his wing. All the faculty members were Rachmaninoff’s closest friends; they taught him well and, in the end, produced a miracle like him. If you want to find out what real Orthodox singing is, listen to the recording of Rachmaninoff’s “Vocalise,” where the composer himself is conducting the Philadelphia Orchestra in America [this recording can be heard here. –Ed.] You cannot understand Rachmaninoff at all if you do not enter into the innermost essence, the most intimate content, that’s incorporated into his Liturgy and his sacred concerto [“The Theotokos, Ever-Vigilant in Prayer”–Ed.]. These are all things that he absorbed, breathed into his innermost self.

In 1918, Trotsky, with a stroke of his pen, abolished the Synodal School and the Synodal Choir. It was a severe blow, a terrible, premeditated crime. Even from a purely secular point of view, because at that time the art of choral singing had achieved perfection, gleaned through centuries of experience; it was the greatest thing that existed in the history of the Russian Orthodox Church in this realm. When the Synodal Choir sang in the Kremlin Dormition Cathedral it was the sound of all Russia praying. Once someone experienced this, they remembered it for a lifetime, and the sound was transmitted from generation to generation. All Moscow sang, the whole of Russia sang.

– In your view, how did choral singing develop after the revolution?

It so happened that in 1923 all the musicians from the Synodal Choir went over to the Conservatory, to this very same choral department. After all, they all knew each other. They did not, however, have very high regard for Alexander Sveshnikov (1890–1980) [choral conductor, founder of the Moscow Choral College, Rector of the Conservatory –Ed.], even though Sveshnikov had a diploma—earned as a part-time student—from the Synodal School, signed by Nikolai Danilin (1878–1945) [the Principal Conductor of the Synodal Choir until 1918, and subsequently Artistic Director and Conductor of the USSR State Choir–Ed.]. The education building that housed the Synodal Choir, along with the Rachmaninoff Hall, where the Synodal Choir sang concerts, have been preserved.

This amazing miracle, the sonority of the Rachmaninoff Hall, made a comeback in my lifetime. [When the Hall was returned to the Moscow Conservatory in 1968, and was being restored for musical purposes,] Viktor Grishin, God rest his soul, helped us; under his iron fist, the builders did their best. The beams were old, and the builders said: “We cannot replace them; even in Siberia there is no cedar to be had, none at all. We will use concrete. This has absolutely no effect on the acoustics.” But to me it was quite clear that this could not be allowed to happen. I remember to this day: a large table in the rector’s office, covered with a green cloth, where all of us were sitting, along with the most prominent members of the building profession. I’m sitting at the end of the table. And God inspired me to say the following: “You see, I have this absolute conviction: if this goes forward, I will not be forgiven.” The room became deathly still, and they said: “We will not do this.” It was nothing short of a miracle.

Later, when I first took the Conservatory’s Advisory Council to tour the restored hall, among them there were the old men who had heard the sound of the Synodal Choir, and they were weeping. The guys sang “Many Years.” What a sound!

– So the room specifically emphasizes the sound of choral singing?

Yes, the sound of the Rachmaninoff Hall is designed for church sound. It was built with the help of master church architects. When I first went in there—it was being used part-time for evening lectures by the Ministry of the Interior—I was horrified: they were using a PA system. And the voice fell flat to the floor. But in fact, the natural singing voice floats in there, because church singing does not tolerate rapid movement.

The hall has special oval openings called “resonators” (golosniki). When word began spreading in Moscow that the Synodal School Hall was being revived, some old-timers came forth, very modestly, who had heard and were familiar with the Synodal Choir. One such person came to me and told me that this room has a secret, which helps regulate the acoustics. Into the resonator, one must put… plain hay. But keep in mind, he said, one must use hay gathered in the temperate zone, well dried naturally during the summer, right under the sun, not artificially in some kiln.

– Was Rachmaninoff’s Vigil performed in Russia [during the Soviet era]?

No. I had appealed to the Ministry of Culture —absolutely not allowed. Some time later [in the early 1960s–Ed.], after much effort, Sveshnikov began working on a recording. This recording was released by the “Melodiya” label, but one could not buy it here. And suddenly in Paris—an explosion! Accolades for Sveshnikov: “A discovery! A miracle!” and, most tellingly, “We did not know the real Rachmaninoff!” Then the Americans realized that they could make money on it, and began to say that it was they who had saved him. Well, what can one say, perhaps they truly did save him from starvation.

– What do you think about the revival of church music education for children?

This is a very complex, thorny, yet sacred problem. We must all make an effort to recreate a semblance of the Synodal School, where boys would live and be taught in residence.

Many sincere efforts have been made towards solving this problem. One former student of mine, Father Victor Shkaburin, has established a singing school for boys. At the Moscow Representation Church of the Holy Trinity-St. Sergius Monastery boys also participate in choral singing. They’re just kids, but it’s already a step in the right direction!

Generally speaking, the best place to hear genuine church singing, in my opinion, is right here, at the Church of the Trinity at the Representation (Podvor’ye). And of this I can speak confidently. Vladimir Gorbik is a great conductor. At a festival-competition of sacred music in Poland he took first place. To me this is particularly precious, because he is a student of one of my students. Oftentimes among church choir directors one sees the most elementary levels of conducting, simply “waving the hands around”; but here such is not the case, and that is a good thing.

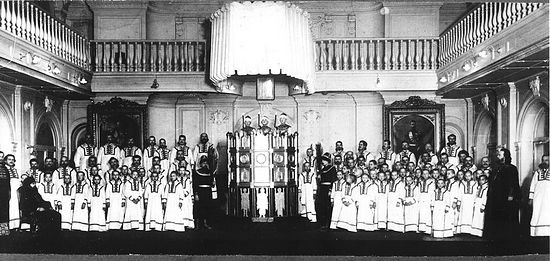

Choirs of the Moscow Representation Church Perform in the Rachmaninoff Hall of the Conservatory (2008)

Choirs of the Moscow Representation Church Perform in the Rachmaninoff Hall of the Conservatory (2008)

– Do you think there are presently successful works in the realm of sacred music that are little known to a wider audience?

Of course. Nikolai Sidelnikov composed well, but he is already dead. He was a very faithful believer. Alexey Larin composes well. Very good compositions are being written now by Anatoly Kiselev. His works were performed when Victor Popov (1934-2008)[Founder and Artistic Director of the Bolshoi Children’s Chorus and the Moscow Choral Academy—Ed.] was still alive. This was a joint performance of the men’s choir with the choir of boys.

– If I may—three traditional questions. What does the Representation Church mean to you and why do you attend this church in particular?

First of all, there is a relationship here among the active participants in the life of the Representation Church. There is an absolute prayerful unity of the building, the services, and the clergy. It seems to me that this is a very rare and very purely manifested example of our existence, our striving as Orthodox believers.

The musical aspect of the services here is so moving, so precisely and beautifully integrated with the service. Gorbik is a fabulous director. For me it is important that he speaks with great consideration about Archimandrite Matthew (Mormyl), not only as a great master, but also as a spiritual father. He became fully absorbed in him in order to learn, and he took away a great deal. I find this to be very precious, because I am convinced that here we have a perpetuation of the great [Trinity-St. Sergius] Lavra heritage. And it is being nurtured here very consciously, with great enthusiasm, with care, and with a joyful sense of continuity.

Boris Kulikov with Vladimir Gorbik (2013)

Boris Kulikov with Vladimir Gorbik (2013)

There are special people here, the clergy of the church, from among whom particular personalities shine forth. And, of course, there is a great deal of history here, of which we know so little, even though the Representation Church affected the fates of many people. There is a monastic spirit here, and in order to witness it, one need only to listen to the small evening services, which only the monks attend—this experience is invaluable. After all, this is an arm of the Lavra. Our greatest strength—right here in the center of Moscow! It is impossible not to appreciate it and not to prayerfully welcome it.

– Would you tell us about an instance when God openly manifested His will in your life?

In my life there was a completely obvious case of God’s mercy, intended specifically for me. When the Great Patriotic War (World War II —Ed.) began, my father was taken away on the second day. But he survived, although during the entire war he was on the front lines, and even behind the front lines, since he was a bridge-demolition engineer. After the troops passed by, they would blow everything up. During the war, my mother taught me to pray: I would sit next to her and read, “He that dwelleth in the shelter of the Most High” [Psalm 90]. It was a tangible prayer. Mother told me: “You must write this prayer out in your own hand.” I still have the folder made of shiny green paper, with this one prayer written inside, and on the cover a cross made out of matches.

– What gift from the Lord do you still wish to acquire?

I think that if there is something of value in me, it’s all from my loved ones. Among these I include my friends. True love fills life with great meaning. Events take their own particular course, and relationships also develop in different ways, but I would like to see the Lord preserve them and give them some growth. I believe that the longing for this does not diminish towards the end of one’s life.

Boris Kulikov was interviewed by Sergei and Anna

Sokolov

Translated from the Russian by Vladimir Morosan

Now after a period a silence this tradition is picked up by his former choir member Wanja Hlibka, and slowly he gets there were Jaroff was. Especially after he engaged counter-tenor Bagdasar Khartykian and it was possible again to do that special singing! He was even given the official rights of Jaroff by Jaroffs agent.

Thankfully the people that stayed in Russia during communism now discover this tradition preserved and in november 2013 there was a Symposium on Jaroff in St.Petersburg.

It is the tradition worth looking at!