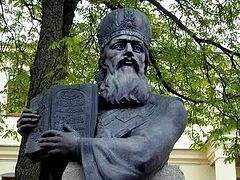

The Holy Synod of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church canonized Metropolitan Peter (Mogila; †1646) as a locally venerated saint in 1996, and nine years later, with the blessing of His Holiness Patriarch Alexei II, his name was included in the Churchwide calendar. Besides his veneration in the Russian Orthodox Church, they have preserved a good memory of him in a number of countries where the pupils of new Orthodox schools labored, where books were circulated, and journals were published by the labors and support of the holy hierarch of Kiev.

St. Peter (Mogila), Metropolitan of Kiev and Galicia

St. Peter (Mogila), Metropolitan of Kiev and Galicia

Metropolitan Peter (Mogila) has had his detractors both during his life and after his death. In 1632-1633, he had to choose between the legalization of the Orthodox hierarchy in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and the “retirement” of the previous metropolitan, Isaiah (Kopinsky; †1640). There were conflicts with monastics, representatives of fraternities, Cossacks… But he also had his associates and admirers. For example, in the second half of the seventeenth-eighteenth centuries, there was a tradition in the Kiev Metropolia of naming boys in honor of a holy hierarch. Thus, the great reviver of monastic intellectual work and the organizer of cenobitic monasticism St. Paisius Velichkovsky was named Peter at his birth. In the nineteenth century, St. Ambrose of Optina highly appreciated St. Peter’s Orthodox Confession. In the twentieth century, the Holy Hierarch of Kiev was criticized, but the positive aspects of his Church-administrative and spiritual-educational activities were also noted.

Metropolitan Peter’s activity continues to interest many people and often cause controversy. Therefore, the question of the holiness of the life of the Kievan Metropolitan is quite relevant.

1. St. Peter became a monk at the age of twenty-nine, abandoning a promising military and political career (in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and perhaps in his native Moldavia) in favor of an eternal, blessed life. Such an act from a representative of the Moldavian boyars—the son of the ruler of Moldavia Simeon (†1607)[1] inspired the Orthodox, whom many in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth considered followers of the religion of a “dying” generation. His life as a monk was filled with constant labors in the field of Church-administration activity, spiritual enlightenment, and personal podvigs. Perhaps that’s why he died young, because he “burned” for the Church, like a flaming candle.

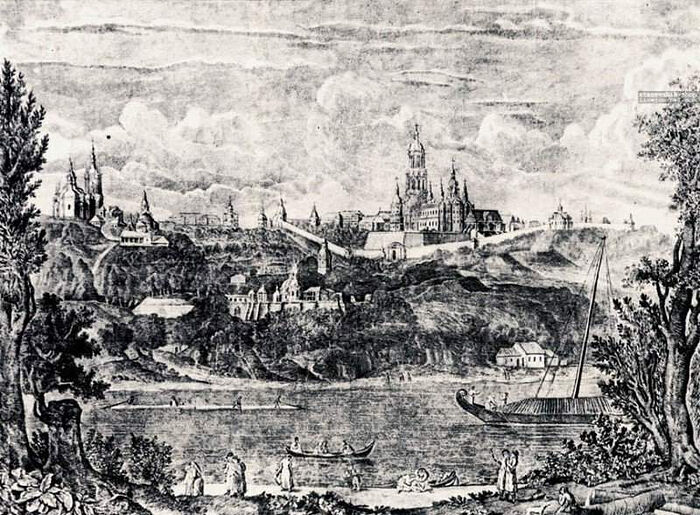

Kiev Caves Lavra. Engraving, seventeenth century

Kiev Caves Lavra. Engraving, seventeenth century

2. The young man’s great administrative gifts, which flowed over into the spiritual plane, brought wonderful fruits not only for the Kiev Metropolia, but also for a number of other countries and peoples. At the beginning of St. Peter’s activity, many Uniates and Jesuit preachers rightly described the decline of ecclesiastical discipline and spiritual piety in the Orthodox Metropolia, thereby supporting their statements about the “gracelessness” of the Orthodox Church—which confused many, even the literate and educated. During the twenty years of St. Peter’s labors as archimandrite of the Kiev Caves Lavra and Metropolitan of Kiev, the Orthodox were no longer accused of all sorts of sins related to weak Church discipline, or a lack of organization of the spiritual and educational life. Priests started getting everything they needed to properly carry out their high ministry: a pastoral example and guidance, education, books, and protection from the lawlessness of heterodox nobles and magnates. Pious traditions were introduced (some of which have remained in the Kiev Metropolia until our times: the celebration of the Passia service in Great Lent with the reading of the Gospel and Akathist to the Passion of Christ, and the especially solemn and magnificent celebration of the Divine services). His Church-administrative activity led to Orthodoxy becoming a respected religion in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and churches, monasteries, and entire dioceses were returned and developed. Uniate figures moved from confrontation to proposing “peace talks.”

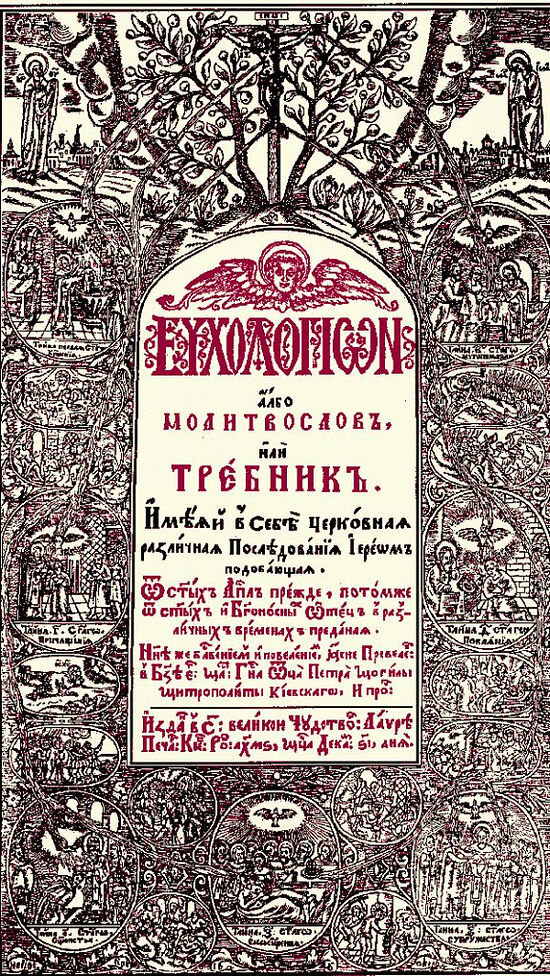

3. St. Peter did much for the development of Orthodox education and academics (including theology). By his own example, he testified that studies in Western European universities don’t just give knowledge in many areas, but can also contribute to the strengthening of the Orthodox faith. The Kiev-Mogila school and the Vinnitsa (later in Goscha) and Kremenets collegia he founded educated a new generation of Orthodox clergy and theologians. In 1629, his Leitugiarion—a service book corrected according to Greek sources and including explanations of the Liturgy—was approved. In 1631, the Pentecostarion was printed with explanations of Church hymns. In the same year, a collection of his teachings was published under the title, The Cross of Christ the Savior and of Every Man. In 1640, a council was held at St. Sophia’s in Kiev, which, besides questions of a liturgical nature and about improving the spiritual life in monasteries, examined the Orthodox Confession, compiled by the Holy Hierarch together with the first rector of the Kiev school Igumen Isaiah (Kozlovsky; †1651). The new Orthodox catechesis had the support of Patriarchs, including of Moscow, and, as already mentioned, had a huge impact on the subsequent history of Orthodox peoples. In 1646, the Euchologion, Albo Prayer Book or Trebnik [Book of Needs—Trans.] appeared, including the rites of the seven Sacraments and the acceptance of Jews, pagans, and heretics into the Church; the rites of various consecrations: of water, churches, monasteries, homes, Church items, and so on; and special educational and instructive texts, on how pastors should teach their flocks.

St. Peter’s Book of Needs, 1646

St. Peter’s Book of Needs, 1646

From the times of St. Peter, representatives of other Christian confessions began to convert to Orthodoxy, which in and of itself is a high indicator of the Church-educational activity of the Kiev Holy Hierarch. It should be understood that at that time, the development of education and the humanities in Europe was connected with the activities of the Catholic church (and the Protestants). Therefore, the use of the European experience led to Orthodox education and theology being outwardly similar to that of Catholicism. But the worldview of the Holy Hierarch-enlightener, including his knowledge of Greek works, was a synthesis of bold Orthodox responses to challenges connected with completely new cultural and intellectual conditions in the world of that time. Responsibility for the “Latin captivity” of Orthodox theology lies with those for whom the traditions of the Fathers of the Eastern Church ceased to be relevant for various reasons.

4. St. Peter was merciful. He proved with his life that, having found the Gospel pearl—a symbol of the Heavenly Kingdom—it’s possible and necessary to give away everything earthly. Although he fled his homeland, he had influential relatives in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth,[2] so even in his new land he had several estates (in the Belz and Kiev Voivodeships). While still an archimandrite, he generously donated to churches, and built an almshouse at the Kiev Caves Lavra. In fact, he “invested” all his main property into the Kiev Metropolia. Taking advantage of his fame as a selfless philanthropist, he also gathered donations to restore and build churches, including from the Tsar of Moscow and other wealthy individuals of the Russian state of that time. Many monasteries and churches of today’s Ukraine were built by the efforts of St. Peter. A considerable number of churches of various countries from the Adriatic and Aegean Sea to the Arctic Ocean received free of charge books written and published by the Holy Hierarch and his ascetics. Even the archives of countries like Hungary (where there are very few Orthodox) house books from the time of St. Peter.

5. He was a peacemaker and didn’t allow a schism in the Kievan Metropolia, although he had some very difficult tasks to solve. Despite some harsh measures in the administrative life of the Church, when imposing discipline among the clergy, he managed to find compromise solutions to carry out these tasks. He managed to find a common language with fraternal organizations that were advocating for Church reforms and an increased role for the laity. The fraternal movement was directed towards educational and Church-social activities. An illustrative example of this is the Kiev collegium that arose as a merger of the Fraternal School and the Lavra School of St. Peter. A former soldier, and now a warrior for Orthodoxy, he didn’t fear confrontation with the Cossacks and didn’t allow their leaders to use the Kiev Metropolia as a “bargaining chip” in the confrontation between the new Ukrainian elite and the central authority and magnates of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. He also attempted reconciliation with Metropolitan Isaiah (Kopinsky) in 1637.

The veneration and canonization of Vladyka Peter (Mogila) testifies that the Church blesses all the courageous actions of his spiritual children, aimed at the strengthening and prosperity of Orthodoxy.