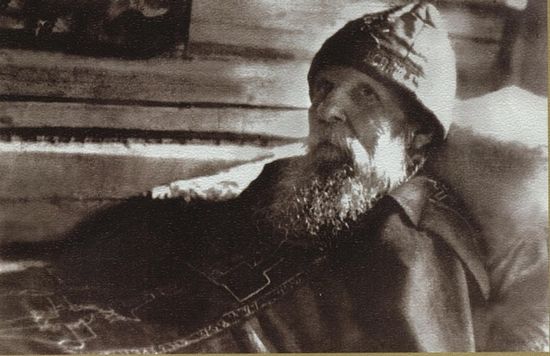

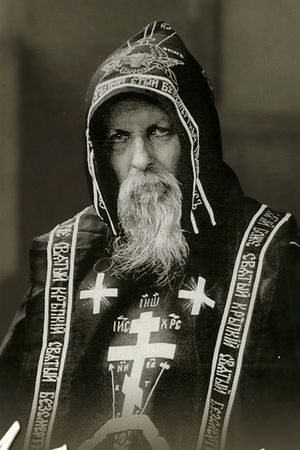

April 3, 2014 was the 65th anniversary of the day of the repose of Saint[1] Seraphim of Vyritsa—the great saint who cares and prays not only for St. Petersburg[2], but for the whole Russian land. My grandmother, Tamara Vasilievna Bakanova, was fortunate enough to have visited him more than once, and to have sought and obtained his advice. Taking advantage of the opportunity, I’m setting down in writing her memoirs about St. Seraphim—what my mother, the Honored Dr. Galina Georgievna Vasilik, remembered and what was deposited, in its own time, in my memory.

They will drive you away, they will kick you out.

During the War Vyritsa was occupied by the Germans. By the prayers of St. Seraphim, there was no destruction there or great loss of life. But they drove the Pioneer camp children who had been captured in Vyritsa into the camp, where many of them perished from hunger or cruel treatment. The Germans established their own order everywhere. They settled in like overlords, like a race of masters. They chose the best houses. To this day, the old-timers call one of the houses “Miller’s house,” after the name of one of the officers who was quartered there. And so, the German officers found out that there lived in Vyritsa a certain old man who could tell the future and who knew the present.

Out of a healthy curiosity, some of them would go visiting St. Seraphim at his home on Pilny Proyezd. They would ask him, “Old man, which houses do you advise us to choose—so they would be solider and we wouldn’t have to waste money on repairs?” But St. Seraphim? said to them, “Which houses? What are you talking about? They will drive you away from here. They will kick you out. And you will not see your Germany.” The Germans flew into a rage, and one of them took out his revolver and began to brandish it, “Oh, we’ll shoot you right now, then!” But the saint (who was already bedridden) answered quietly, “Go ahead and shoot. I only have a little time left now. ‘For me to live is Christ, and to die is gain’ (Philipp. 1:21).” The Germans spit in annoyance and left.

And in 1944 St. Seraphim’s prophecy was fulfilled: the Soviet army bombarded the German scourge with barrage fire and cleansed the vicinity of the city of St. Peter—including Vyritsa—of them. God only knows where St. Seraphim’s unfortunate visitors piled up their blueblood bones. It is only known that St. Seraphim prayed for Russia’s victory for a thousand days and nights (practically the whole of the Battle of Leningrad).

He’s a convict!

The Dementievs were among St. Seraphim’s spiritual children: the mother (it seems her name was Maria) and her daughter Tatiana. They were from a merchant family, the family’s father maintained a tea shop before the revolution, where a real live Chinaman opened the door for the customers. Dementiev had probed deeply into the secrets of the art of tea, for which purpose he had travelled both to India and China. In the heat of the NEP,[3] they sent Dementiev to places that were under guard, as a member of the leisure class. True, they changed their mind later—the young Soviet Union had to set up a tea business. People from the NKVD came to his wife, “Where is your husband?” She only shrugged her shoulders, “You arrested him—you’re the ones who should know.” And that’s how he disappeared into the northern camps, carrying away the secrets of his tea mastery with him into the permafrost.

But his widow remained to bring up little Tanya. And she raised her. The daughter grew up to be bright, beautiful, and believing.

After the war a certain young man started to court Tanya. His name was Nikolai. A Candidate of Engineering Science,[4] the senior researcher at a serious scientific research institute, who was working in defense. He courted her beautifully and tactfully. Each time he saw her he would bring her flowers and sometimes other presents. He was polite and attentive, he called every day—in general, he was the suitor of suitors. They set a wedding date for the near future.

But Maria, Tatiana’s mother, decided to make a trip to St. Seraphim before this—not so much for advice as for a blessing, so that everything would go well for the young couple. She walked up to Fr. Seraphim and asked:

“Batiushka, do you bless me to give my daughter in marriage?”

“To whom?”

“To a good person.”

“What kind of good person?”

“A good person. An engineer in a defense institute. And he is ready to get married.”

And she said his first and last name. Hearing this, St. Seraphim sighed softly and waved his hand:

“What are you thinking, Matushka? Do you understand who you are giving your daughter to? He’s a convict! A convict! What wedding? What crowning?[5] His prospects are for Vladimirka.[6] The Great Siberian Way is in store for him."

Maria left Vyritsa feeling completely confused. On the one hand, you couldn’t disobey Batiushka; on the other, she didn’t want to lose a good son-in-law. But most of all the words, “He’s a convict” struck her. She was trying to remember Nikolai’s face and behavior. What was there about them that was like a convict? His appearance was entirely well-meaning… She returned from Vyritsa to Leningrad. She wasn’t going to say anything to her daughter for a while.

And then something strange began to happen. Before, Nikolai had called every day, and came to see Tatiana almost every day. But now, he didn’t call for a whole day, then two, then three—and finally a whole week… Maria and Tatiana began to worry: what does such silence mean just before the wedding? Could he really have changed his mind and gotten cold feet? What an insult to the bride! Or did something happen? They called the apartment where he lived. They couldn’t make any sense out of it, they heard some sort of strange answers: “Who are you? What do you want him for?” They travelled to his apartment and heard, “He doesn’t live here any more.” And the tenants acted kind of strangely and wouldn’t look them in the eye.

Finally Maria decided to take an extreme step—she travelled to Nikolai’s workplace. They greeted her there even more strangely than at his home. Everyone avoided her like the plague. They wouldn’t give her a straight answer to her questions. Finally, the elderly head of personnel felt sorry for her and invited her to his office and related the following to her:

It turns out that a while ago the defense of Nikolai’s doctoral dissertation took place. The dissertation was brilliant. Everyone complimented him on it, until the line came to one elderly professor. He stood up and said, “Friends and colleagues. I don't care, I only have a little while left to live. I have to tell you the truth about this dissertation. It’s plagiarized. It was copied from the work of our former colleague A.M., whom I supervised.” Everyone was horrified: A.M. had been arrested on Article 58.[7] But the proof of plagiarism was weighty and the matter could not be suppressed. As the subject was about a secret military project, the main points of which were stolen by Nikolai, the case sparked the interest of the appropriate authorities. And it turned out that Nikolai, having become acquainted with the text of A.M.’s dissertation, wrote a report against him to the authorities and also stole his work and his invention. And they arrested Nikolai for this. Thus was fulfilled St. Seraphim’s prophecy, “He’s a convict.”

Matushka will Feed Everyone

St. Seraphim’s spouse, Mother Seraphima—in the world Olga Ivanovna Muraviev,[8] died in 1945. When Vasiliy Ivanovich Muraviev (the future St. Seraphim of Vyritsa) and Olga Ivanovna separated by mutual consent in 1920, she (O.I) went off to Novodevichy Convent. After its devastation and closing, and a whole series of temptations, in the final analysis she found herself in Vyritsa, where she took care of Fr. Seraphim, who was seriously ill. She died on April 4/17 from an extensive stroke.

Many people came to pay their respects and to remember her. It was during a time of famine, and St. Seraphim had practically nothing. His helper came up to him and said, “Batiushka, the people are coming from the funeral, but we don’t have anything to feed them with—there’s only one pot of kasha[9] for everyone.”

But St. Seraphim answered, “That’s all right. Give what there is. Matushka will feed everyone.” During her lifetime, Mother Seraphima had been very hospitable.

And then came the people, one after the other. And for all of them one pot of buckwheat kasha. Fr. Seraphim’s helper began to feed them and saw that the level of the kasha was not getting any lower—there was enough for everybody. And finally the last visitor left, and the helper saw that there was still kasha along the sides of the pot. A miracle. Just like at the feeding of the five thousand with five loaves. She ran to the starets[10] and said, “Batiushka! There was enough for everyone. There is still some kasha around the inside of the pot.” And St. Seraphim smiled and said, “Well, I said Matushka would feed everyone.”

I read an article by Deacon Vasilik from a Byzantine Studies congress in Denmark in 1996 and I am trying to contact him to ask 2 questions about this incredibly interesting paper.

I am a musicologist at the Sorbonne in Paris working with the earliest evidence of hirmoi and canons on papyrus in the 5th-7th centuries.

Thank you very much for helping me to contact Deacon Vasilik.

Sincerely,

Alan Gampel