Theodore lost his father at a young age. After her husband’s death and a fire that destroyed all the family’s property, his mother moved with the children to the home of her brother, the wealthy Petersburg merchant Nikitin. But Theodore was burdened by the worldly vanity and went whenever possible to the St. Alexander Nevsky Monastery for services. At age thirteen, seeking heavenly treasures, the boy was able to ask his mother to let him go and live permanently in the St. Alexander Nevsky Monastery.

A half-year later, at the advice of his spiritual guide, Theodore transferred to Sarov Monastery, which was at that time famous for its holy elders (St. Seraphim of Sarov, Hieromonks Ephraim, Pachomius, and Pitirim). For the young novice such a monastery was a grace-filled school—monastic piety was strictly preserved there; long, heart-warming services that followed the established rubrics elevated his soul. The ascetics who spiritually adorned Sarov Monastery instructed and raised up monks not only by their own example, but also by their wise and refined knowledge of the human heart. Theodore passed through various obediences in this monastery; he was the bell ringer for three years, worked making bread and kvass [a beverage made from rye bread], labored for three years in the prosphora bakery, and then carried out the obedience of altar attendant.

From Sarov Monastery Theodore transferred to the Moscow Simonov Monastery, where his older brother Archippus was a novice. Here Theodore was tonsured a monk with the name Philaret (in honor of Righteous Philaret the Merciful, comm. Dec. 1) on April 4, 1786. On May 8, 1787 he was ordained a hierodeacon.

During his time in Simonov Monastery, Philaret had a beneficial influence on his mother, who was a novice in the Novodevichy Monastery. He convinced her to accept the tonsure, which she had declined out of humility and lack of confidence in her own strength. After she received monasticism, her son found her weeping. She said that she couldn’t fulfill her obligations to the letter. “Then Philaret consoled her and promised to pray for her, so that the Lord would give her His graced-filled strength to bear the difficulties and temptations.[1]

In 1788, Metropolitan Gabriel (Petrov) called Hierodeacon Philaret, as a monk of strict life, to St. Petersburg and placed him among the brotherhood of the St. Alexander Nevsky Monastery (from 1794, Lavra). In the following year of 1789, Metropolitan Gabriel ordained him a hieromonk. “That His Eminence Gabriel so valued the spiritual experience and knowledge of monastic life in Fr. Philaret when they became acquainted can be see from the fact that when at long last he received from Moldavia elder Paisius Velichkovsky’s translation from the Greek of The Philokalia and gave it to the scholars of the St. Alexander Nevsky Seminary for review and correction, he gave them the order to council with spiritual elders who had in in real life passed through the exalted teaching of spiritual contemplative life and mental prayer that is offered in The Philokalia. One of these elders was Fr. Philaret.”[2]

In February 1791, Hieromonk Philaret was appointed head of the metochion of the Novgorod Yuriev Monastery located in the Kitai-gorod neighborhood. He served in the Church of Prophet Elias belonging to the metochion. Ruling the metochion was bound up with many daily cares, which corresponded little with Fr. Philaret’s prayerful disposition. On July 7, 1794, he was released from this position at his own request.

In September 1794, Hieromonk Philaret was sent to the Novospassky (New Savior) Monastery for obedience in the infirmary. He served in turns in the St. Nicholas infirmary church. As one of the members of the spiritual council established at the monastery, Fr. Philaret participated in the leadership of the monastic community. This took place at the time when the fathers superior of the monastery Archimandrites Methodius (Smirnov; † 1815), Ambrose (Yakovklev-Orlin; † 1809), Anastasy (Bratanovsky; † 1806) were spending long periods of time in St. Petersburg, participating in the work of the Holy Synod.

In 1798, Hieromonk Philaret, as an experienced instructor of spiritual life, was chosen by Archimandrite Joachim (Karpinsky; † 1798) and all the brothers as the father confessor for the Novospassky Monastery. However, in the next year, in 1799, due to extreme exhaustion and physical weakness Fr. Philaret was relieved of all duties. From that time on he spent his time in prayer, reading of the works of the holy fathers, and other spiritual books. He left the monastery very rarely. Fr. Philaret associated with people who were close to him in spirit, such as Hieromonk (from 1810, Archimandrite) Alexander (Podgorychani; † 1825), who came from the Florischeva Hermitage in the Vladimir diocese. This meek man of prayer was a disciple of and tonsured by the great elder, Paisius (Velichkovsky).

Hieromonk Philaret spent several years in strict hesychia. This ascetic labor prepared him for his lofty service as an elder, which began in 1809 or 1810. Only the French invasion in 1812 disrupted the outward order of his life. While the French were occupying Moscow the elder left with the family of N. I. Kurmanaleyeva to her Vologda estate. Along the way he visited the Yakovlev Dimitriev Monastery of the Savior, where his mother had been buried not long before.

“After returning to Moscow, Elder Philaret continued almost to his very death to instruct his neighbors and to help them. His cell, especially during the later years, was daily filled with a multitude of people from all strata of society, from upper level dignitaries to the lowliest simple folk. Disturbed with doubts, wounded by passions, afflicted with bodily sickness or other catastrophes, people streamed to Elder Philaret from all over the country to pour out their souls, their sorrows, and found true fatherly sympathy in him. It often happened that because of the many visitors the elder had no time to eat or even take a short rest, regardless of the tormenting illness (hernia) that he himself suffered continually. God’s grace strengthened the elder in his weakness, and by the action of that same grace, no one who came to him ever left without having received consolation or edification. In his conversations were particularly clearly shown the marvelous meekness of his soul, his great humility, fervent love of neighbor, co-suffering, patience, and the strength of deep spiritual knowledge. The elder’s clairvoyance was astounding—it would happen that someone would tell him something contrary to what he knew or felt, and as if listening to the story, the elder would answer directly to the inner disposition of that person, who would come to a state of fear and confess the truth.”[3]

This description, made by the elder’s contemporary, calls to mind the lives of other great spiritual instructors, who by the holiness of their lives and spiritual wisdom drew hundreds and thousands of people to themselves, people who were suffering spiritually and bodily. Primarily we recall the famous Optina elders.

The grace-filled gifts that Fr. Philaret acquired brought great benefit to people: They were healed of spiritual and bodily infirmities, their lives were corrected, and they were consoled in their sorrows. Here are a few examples taken from the elder’s Life and “from reliable sources.”[4]

Colonel N. N., age forty, quite learned and intelligent but drawn into freemasonry, spent several hours in conversation with the elder, displaying his cleverness and erudition. At the end of the conversation he said to the elder, “I supposed that you were a knowledgeable remarkable man, but you are only a simple monk. When I came here I said, ‘Peace be to thy house’ (cf. Matt. 10:12), and now I regret that I came; you are incapable of understand higher things.” Fr. Philaret with meekness and gentleness answered, “Indeed, you will not find in me anything remarkable; but I, by God’s mercy, have read sacred books, and it seems that I understand them a little. The holy apostle says, But he that is spiritual judgeth all things, yet he himself is judged of no man (1 Cor. 2:15). Having cited this text, the elder continued to speak with such power, such conviction, that the colonel and the others with him looked at him in amazement. His speech went on for a half hour, and when it ended the colonel fell to his knees and cried out in tears, “O God-inspired elder! Forgive my madness, forgive me; allow me to come to you to learn and be strengthen in the saving truth; permit me to be your obedient son.” The elder with the same meekness expressed his consent and accepted him among the number of his spiritual children. The colonel as a result not only abandoned his false convictions, but also became a zealous Orthodox Christian.

A peasant of Countess Orlova-Chesmenskaya told the elder tearfully that her son, the clerk of a Moscow trader at the Kaluga market, was sent by his employer to collect debts and had disappeared without a trace for several weeks now. “Sit down, my friend,” the good-natured elder said to her meekly and mercifully. “That’s enough crying. Your son has not disappeared; he is in a good place and will soon return.” And truly, he did soon returned. Instead of collecting money he tried to join one of the distant monasteries, but having no passport he was not accepted anywhere and had to return. A little while later this young clerk at his mother’s suggestion came to the elder to ask his blessing to enter a monastery. The wise elder said to him, “It doesn’t take long to bless for a monastery, but it is hard to live in a monastery, and you won’t be able to do it. Wait a little, my child, wait!”

The niece of General L-n, Ekaterina, came to Fr. Philaret together with her fiancé. The elder blessed the future bride, and told her quietly that a better bridegroom awaits her. Three days later she caught a serious cold, and without entering into marriage was transported on the wings of death to the heavenly abodes, where where Christ sitteth on the right hand of God (Col. 3:1).

Certain people said to Fr. Philaret that they go to N. to ask about the future. The elder advised them not to go to him. “What he says does come true, but one has to be capable of understanding it,” the wife of the merchant D-v. protested. The elder answered, “Perhaps what he says to you comes true, but it’s dangerous—you can lose your mind. I’ve seen many people in pitiful states from such prophecies. I advise you to go to the Liturgy every day, and not to go to N., or you’ll be harmed. She didn’t heed his advice and in a few months or less became mentally ill.

A young man who was demonically possessed was brought to NovoSpassky Monastery. He was bound with chains. Five strong men were barely able to restrain him. The unfortunate man’s facial expression was horrifying. They could barely drag him to the elder’s cell, and he fought and shouted terribly. The elder went out to meet him, and asked those around him to free him and take off the chains. But they couldn’t get themselves to do it for fear that the demoniac would kill them and leave. Then Elder Philaret with his customary meekness himself began loosing the bonds on his arms and said, “In the Name of the Lord, be obedient.” The sick man shuddered and became as if rigid, not being able to walk. The elder took him by the hand and led him into his call, holding him there for a long time (most likely he was reading the prayers of exorcism) and then, giving him back to his relatives, told them to bring him back in two days. It is well known that the sick man, who had suffered for more than six years and terrified his family, received complete healing through the elder’s prayers, proving the power of Christ’s words: In My Name shall they cast out devils (Mk. 16:17).

Schemamonk Zosima (Verkhovsky; 1767–1833), who founded the Holy Trinity-Hodigitria desert community for twenty of his women disciples who had come with him from Siberia, after six years of spiritual instructorship in the new monastery wished to leave his spiritual children and go to Solovki Monastery, begging them not to prevent him and promising to return in four years. All the sisters were sad, and wandered around lost in silence. The elder himself could not hold back his own tears, but decided to fulfill his desire after first spending some time in Moscow. Along the way, his soul experienced a fierce struggle between two feelings: Love inclined him towards compassion for the sisters and persuaded him not to abandon them, but humility suggested that he was not worthy of their respect, love, and obedience. This is what drew him to leave. The elder wished to die a simple pilgrim. In such perplexity and struggle he wanted to learn what was God’s holy will. He prayed fervently about this. Then the good thought came to him to ask the advice and prayers of a spiritual and experienced man, and to receive his words as from God’s lips. Metropolitan Philaret, his spiritual instructor, was not in Moscow at the time—he was at the Holy Synod in St. Petersburg. Schemomonk Zosima turned for resolution to his perplexity to Fr. Philaret in the NovoSpassky Monastery, whose spiritual wisdom and long experience in monastic life he knew. As he went to him he stopped at the Iveron Chapel of the Mother of God and fervently prayed before her holy icon, asking her to reveal to him the will of God through elder Philaret. Entering his cell, Zosima humbly bowed down to the elder’s feet and told him everything. Fr. Philaret said categorically and firmly, “For God’s sake do not abandon the souls entrusted to you; go back. Their love, faith, and obedience to you is to their benefit, and not harmful to you; do not deprive them of their reward for their zeal and obedience to you. Not knowing about their salvation or place of living might darken the final minutes of your life, while your repose can be profitable and edifying to your flock.” Elder Philaret’s words put Schemamonk Zosima completely at peace. He joyfully returned to the sisters, who had not ceased weeping from the moment of his departure.

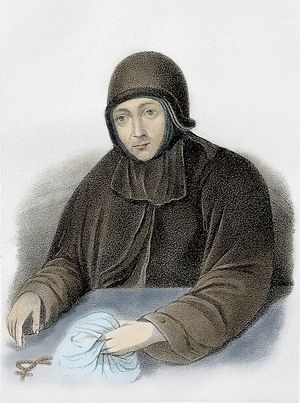

Fr. Philaret was also closely united by the bonds of mutual respect and prayer with the ascetic of piety Nun Dosithea. His spiritual daughter N. I. Kurmanaleyeva related how after the death of her husband she went to Nun Dosithea in the monastery of the great prophet John the Baptist, but she was not able to see the eldress. She went to Elder Philaret. “With bitter tears I told Fr. Philaret that misfortune was stalking me on all sides, that God did not allow me even to see the recluse nun and ask her holy prayers. The elder replied, “It’s true, she does not receive anyone, but try once more to go to her.”[5] With particular persistence, Kurmaneleyeva was vouchsafed a meeting. The ascetic advised her to find a spiritual guide. “In those minutes I remembered and named Fr. Philaret. At the mention of that name the recluse quickly rose and bowed to my feet, saying, ‘You fortunate one, you know that great elder and wanted to see me, a worthless sinner! Hold on to that elder—he is a great pleaser of God. Follow and fulfill his words, reveal your conscience to him, and God will save you… Go to him right now and tell him that sinful Dosithea bows to the ground to him and asks his holy prayers, and that soon he will also bow to me’.”[6]

A few days later Nun Dosithea (February 4, 1810 at the age of sixty-four) was vouchsafed a blessed death. “The reposed one wished to be buried in the Novospassky Monastery opposite the window of his (Fr. Philaret’s) cell. On the day of her burial, when they brought the recluse’s coffin to the holy gates of the monastery, I saw batiushka making a prostration to the ground before the coffin of the reposed.”[7]

We must particularly tell of the beneficial influence Elder Philaret had on people whose labored for the good of the Church. The abbot of Optina Monastery Schema-Archimandrite Moses (Putilov) before monasticism would take counsel with the Novospassky ascetic. In a letter to Maria Mazurina, the builder of the St. John Convent, not long before his death (June 16, 1862) he wrote, “Living before in the St. John Convent, the spiritually wise eldress Dosithea of blessed memory served to direct me on my chosen path of life of the monastic calling; she acquainted me with Elders Alexander and Philaret in the Novospassky Monastery, where she is buried.[8]

In the Life of St. Macarius of Optina there is valuable information about the profound respect he had for the Novospassky ascetic. “On the return journey from Petersburg, Fr. Macarius had the consolation of while passing through Moscow to visit the elder Hieroschemamonk Philaret in Novospassky Monastery; his spiritual conversation and profound wisdom, penetrated with the power and light of grace, and his love were forever imprinted in Fr. Macarius’s heart.[9] Fr. Macarius kept a portrait of Elder Philaret in his cell.

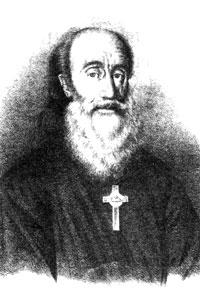

Indebted to the Novospassky elder for his conversion to Orthodoxy was the remarkable philosopher Ivan Kireyevsky. Educated on the ideas of German philosophy, he was far from Church life. Having married Natalia Petrovna Arbenina in 1843, he became acquainted with her spiritual father, Elder Philaret. Kireyevsky’s friend, Alexander Koshelev, recalled how the distinguished philosopher of our culture became an Orthodox man and deeply religious. “I. V. Kireyevsky never wore a cross before. His wife many times asked him to do so, but Ivan Vasilievich kept silent. Finally, one day he said to her that he would put on a cross if Fr. Philaret sends him one, for he had long warmly respected his mind and piety. Natalia Petrovna went to Fr. Philaret and told him this. The elder crossed himself, took off his cross, and give it to Natalia Petrovna saying, “May it be for Ivan Vasilievich unto salvation.” When Natalia Petrovna returned home, Ivan Vasilievich met her and asked, “Well, what did Fr. Philaret say?” She took out the cross and gave it to her husband. Ivan Vasilievich asked her, “What cross is this?” Natalia Petrovna told him that Fr. Philaret had taken it off himself and said, may it be for him unto salvation.” From that moment, a decisive turnaround could be noticed in the thoughts and feelings of Ivan Kireyevsky. After Fr. Philaret’s repose, Ivan Kireyevsky lived near Optina Monastery, often conversed with fathers Leonid and Macarius and other elders, and became stronger and stronger in piety.”[10]

Hieromonk Philaret was distinguished as remarkably well read. From the works of the holy fathers he made notes of instructions that he especially liked. With his own hand he wrote down some complete works of Saints Maximos the Confessor and Simeon the New Theologian, which at the time had not yet been printed.

Fr. Philaret was a monk of austere ascetic life. He ate only porridge and that only once a day, and drank tea with a crust of bread. On other days (mainly on Thursdays) he took only prosphora. On Monday, Wednesday and Friday he always, except on feast days, abstained from food altogether. He spent Great Lent especially austerely. On the first week and Passion Week he ate no food at all, drinking only a little warm water in the evening.

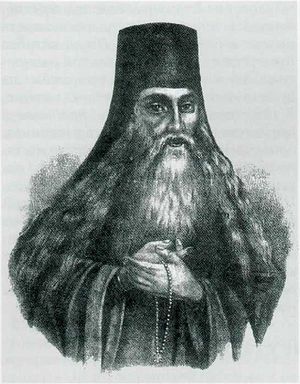

In 1826, Hieromonk Philaret was tonsured in the great schema in his cell by the Athonite hieromonk Innocent, who was in Moscow at the time. He was given the name Theodore. However the elder’s outward life did not change. Just as before, he received a multitude of people, giving them saving instructions, consoling and healing.

Fr. Philaret foresaw his end. On August 13, 1842, he said, “My time is near. I will be sick for a couple of weeks and then depart.” There is a detailed story in his Life about his blessed repose: “Several days afterward the elder was still quite peaceful, although he felt sick, but he spent the night of August 15 (the day of the Dormition of the Mother of God) in sufferings. On the 16th he significantly weakened, because the inner sickness did not cease, only easing for minutes at a time. “It’s time for my bones to retire,” said the good-natured sufferer on his bed of pain. “What God has ordained cannot be escaped.” On that day he had the consolation of personally receiving the blessing of Metropolitan Philaret (Drozdov). When the elder was informed of the archpastor’s arrival he wept with joy. On the 17th he confessed and received Holy Communion… The elder willed everything he had to the monastery or persons who had served him, and the poor.”[11]

On August 26, the day of the Meeting of the Vladimir icon of the Mother of God, the elder received Communion for the last time. Fr. Jerome, who had come with the Holy Gifts after the early Liturgy and saw the elder extremely worn out by his illness, wept and mixed up the reading of the Communion prayer. The dying man firmly corrected him and finished the prayer. On the evening of August 27, the canon for the departure of the soul was read over his bed. The great Elder Philaret (Theodore), with prayer on his lips, peacefully and quietly died on August 28 (September 10, new style) in the eighth hour after midnight.

On the day of his burial, August 31, a Liturgy for the departed and funeral were served according to the monastic rite in the Transfiguration Cathedral of the monastery by the holy hierarch Philaret, Metropolitan of Moscow. “During the singing of the moving antiphons, “When I sorrowed, thou hast heard my pain, O Lord I call unto Thee…”, “He who dwells in the desert abide in divine desire, far from the vain world…” an extraordinary quiet reigned among the large gathering of people in the church—all were reverently attentive… As soon as they began to sing the third antiphon, “I have lifted up the eyes of my heart to Thee, O Savior…”, the metropolitan could no longer restrain his tears. Then many others around the coffin also broke into tears. The Metropolitan’s farewell to his much-suffering namesake profoundly touched everyone. During the burial there was such a great stream of people in the Novospassky Monastery as no one remembered, even on August 6, the monastery’s patronal feast (the Transfiguration). Not only the inside of the monastery, but also the bell tower, the roofs of the cells and outer wall were filled with people. When the body was lowered into the earth, someone said, “There has never been such an elder in the New Savior [Monastery].[12]