The following is the complete text of a Lecture delivered by Bishop Irenei at the University of Fribourg, 31st October 2019, addressing the serious problems with modern-day attempts to develop a so-called “Trinitarian” vision of Church life that attempts to correlate the relations between ecclesial authorities to the relations of the Divine Persons of the Holy Trinity—especially as manifest in the false claims of any one patriarchate as having authority precedent to all others on such theological grounds.

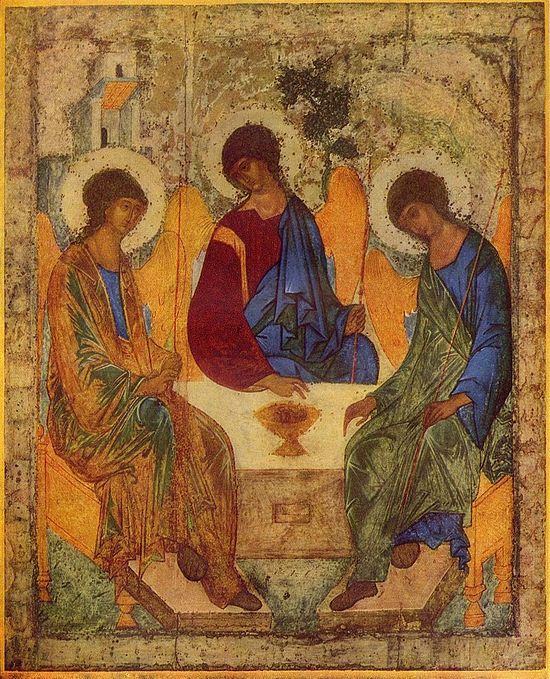

For some years now, there have been currents within Orthodox theological discussion that have increasingly blended together Trinitarian theological principles with those of structural ecclesiology: that is to say, the nature of God as Trinity-in-unity with the Church as multiplicity-in-unity. This has been manifest in various studies and texts, perhaps none more visible to the public gaze than the controversial ‘Ravenna Statement’ issued in 2007 by the Joint International Commission for Theological Dialogue Between the Roman Catholic and Orthodox Churches. The main point of contention over that document’s release (which concerned incomplete Orthodox participation in its drafting due to ecclesial circumstances at play at the time) do not greatly relate to what is, in my mind, the far more questionable issue of its Trinitarian ecclesiological focus. The Ravenna Statement opens its primary content by noting that the Church’s “Conciliarity reflects the Trinitarian mystery and finds therein its ultimate foundation,”[1] going on to explain that:

The Eucharist manifests the Trinitarian koinonia actualized in the faithful as an organic unity of several members each of whom has a charism, a service or a proper ministry, necessary in their variety and diversity for the edification of all in the one ecclesial Body of Christ (cf. 1 Cor 12.4-30). All are called, engaged and held accountable—each in a different though no less real manner—in the common accomplishment of the actions which, through the Holy Spirit, make present in the Church the ministry of Christ, the way, the truth and the life (Jn 14, 6). In this way, the mystery of salvific koinonia with the Blessed Trinity is realized in humankind.[2]

This had put even more emphatically in an earlier document produced in Munich, which provided a foundation for the discussion in Ravenna:

Since Christ is one for the many, as in the church which is his body, the one and the many, the universal and local are necessarily simultaneous. Still more radically, because the one and only God is the communion of three persons, the one and only church is a communion of many communities and the local church a communion of persons. The one and unique church finds her identity in the koinonia of the churches. Unity and multiplicity appear so linked that one could not exist without the other. It is this relationship constitutive of the church that institutions make visible and, so to speak, “historicize”.[3]

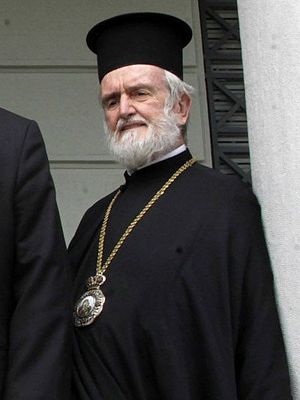

Metropolitan John (Zizioulas). Photo: wikipedia This paradigm—of seeing the structural-administrative elements of the Church in terms of the koinonia of the Trinity, manifest in a specific taxis or order—runs through much of the Commission’s textual output, and certainly throughout the Ravenna statement, giving shape to its entire ecclesiological vision,[4] much as indeed it represents the voice of its chief Orthodox theological author, Metropolitan John (Zizioulas) of Pergamum.[5] The relations of the Trinity are the starting point, and continual reference point, for considering the structural elements of the Church. As I shall make clear in what follows, there are serious problems—both theological and administrative—with this structural approach.

Metropolitan John (Zizioulas). Photo: wikipedia This paradigm—of seeing the structural-administrative elements of the Church in terms of the koinonia of the Trinity, manifest in a specific taxis or order—runs through much of the Commission’s textual output, and certainly throughout the Ravenna statement, giving shape to its entire ecclesiological vision,[4] much as indeed it represents the voice of its chief Orthodox theological author, Metropolitan John (Zizioulas) of Pergamum.[5] The relations of the Trinity are the starting point, and continual reference point, for considering the structural elements of the Church. As I shall make clear in what follows, there are serious problems—both theological and administrative—with this structural approach.

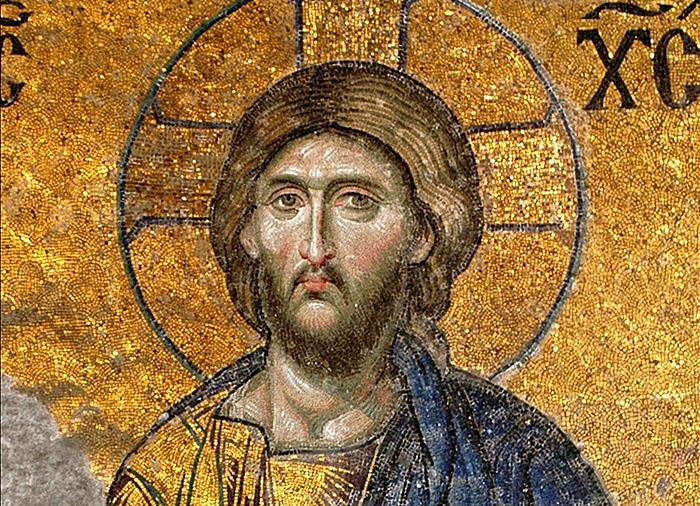

It is natural, perhaps, and seemingly fitting that in a Church that firmly understands herself to be Christ’s Body (therefore explicitly tying her identity to a theological Person), this theological-ecclesiological relationship should arise. This is eminently clear at the Christological level. You are the Body of Christ (1 Corinthians 12.27) has always been understood in Orthodoxy as more than a metaphorical phrase: The community of faithful is a grafting of human individuals into the singular life of the Son, uniting them into one body of which He is the head (Ephesians 4.15). By consequence, this means that the nature, the personal identity, of the One into Whom all are grafted is intimately related to the “structure”, if we might employ such terminology, of the Body into which the members of the Church find themselves drawn. Simultaneously, rightly comprehending the nature of this divine-human Person is a necessary aspect of understanding ecclesiastical structures in all their attributes and functions. Theology and ecclesiology are, indeed, intimately intertwined.

There is an important level at which this is true, too, in the realm of Trinitarian discussion. The Church is the Body of Christ, Who is “one of the Holy Trinity”:[6] it is therefore impossible to comprehend the nature of the Church (and her structure, organization or function) without a comprehension of the manner in which Christ, Whose Body she is, relates in His personal identity to the Father and the Spirit in theirs. Trinitarianism, then, which occupies itself with seeking to gaze into the mystery of the Trinity in an ever more articulate manner, bringing into the realm of human understanding the eternal relations of Father, Son and Spirit, has a perfectly reasonable and indeed essential relationship to ecclesiology, which seeks to understand the way in which the second Person of this Trinity makes manifest in creation the body of His redemptive work.

‘The history of theology is nothing if not replete with the traps and pitfalls of pursuing the logical analysis of what is ‘obvious’ to the peril of what is true.”

And yet, and yet. The history of theology is nothing if not replete with the traps and pitfalls of pursuing the logical analysis of what is ‘obvious’ to the peril of what is true. The great historical arch-heresy of Arius was, in inception, only an attempt at logical analysis of the Son’s “begottenness” in light of the rational implications of this term for temporality and creation. The faults of much-lamented Nestorian dualism were, in origin, attempts at rationally maintaining seemingly contradictory, yet admittedly necessary, confessions about the full deity and humanity of Christ; while the foibles of Apollinarianism (and by extension of the excesses we have customarily labelled “monophysite,” “miaphysite” and even the later “monothelite”) began as logical attempts to confess the incarnate Christ’s singular, subjective identity and take seriously the implications of such famous statements as St Gregory the Theologian’s “that which is unassumed is unhealed”.[7] There are, as the history of developing doctrinal articulation has amply demonstrated, profound dangers in applying rational exegesis to theological revelation in abstraction.

Such is precisely the peril into which a great deal of modern Trinitarian ecclesiology has fallen. One may rightly take as facts of divine revelation that the Church is Christ’s Body, that Christ is a Person of the Trinity, and that He together with the Father and the Holy Spirit exist eternally in specific relation one to another; but the manner in which these realities are linked can be articulated in a multitude of ways—some of which, as we see in our day, lead far from an ecclesiology that resonates with the history of the Orthodox Church.

From Primacy to Trinity

I wish to confine myself here to one specific manner in which a wrong application of Trinitarian articulations to ecclesiological matters has deeply distorted the latter (and, indeed, retroactively revealed problems with contemporary expressions of the former); namely, the application of Trinitarian relations to the hierarchy of ecclesial primacy amongst the churches. This is, perhaps, the area in which the consequences of logical, but ultimately incorrect, analysis of theological-ecclesiological matters have generated “real world” problems in contemporary inter-Orthodox discussion.

While not a theme that historically occupies a central place in the ecclesiological writings of the Church Fathers, the question of “primacy and synodality” has been at the center of ecclesiological discussions of the twentieth and now twenty-first centuries, largely occasioned by the rise, in the mid-twentieth century, of renewed conversation between Orthodoxy and Roman Catholicism, for which the issue is both historically and contemporarily central.[8] Internally, questions of “primacy”, while incontrovertibly present in the writings of the patristic sources, tend not to hold an overly-central place apart from contexts of explicit jurisdictional troubles (it is fairly obvious that questions of primacy should figure, for example, into debates over the relative authority of sees in the ninth- through eleventh-century disputes between Rome and Constantinople). Even in places where there might seem to be rather obvious opportunities to dwell on the issue of inter-episcopal primacy—such as, for example, St Irenaeus of Lyons’ famous excursus on the seniority of the See of Rome in Refutation 3[9]—the Fathers tend not to do so. St Irenaeus, for his part, unequivocally sees Rome as an authority to which others might turn in the task of seeking the doctrinal authenticity of Scriptural interpretation in the face of variant readings, but this is so precisely because of the antiquity of the Roman witness to what is universal amongst all the churches, and not because of any “primacy” possessed by that See as such (and Irenaeus does not use “primacy” here, in what would otherwise be a seemingly ideal place to do so). Having asserted that in Rome the churches have, in terms of the historical flow of time, a most ancient witness to the truth possessed and “traditioned” (handed along) by each of the local churches (and to which those churches can therefore take recourse if ever a question arises[10]), he then swiftly moves on to the ecclesial matters that are of more substantive interest to him: the Church as Body of the incarnate Son; the Church as inheritor of and participant in the Cross and resurrection of Christ; the Church as the nursery of spiritual maturation for Adam as he grows from infancy into adulthood in Christ, etc.[11]

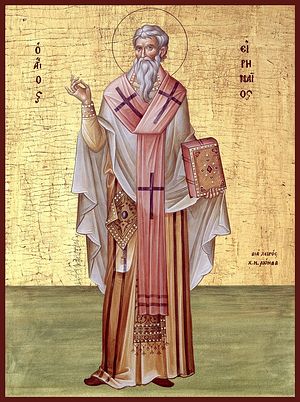

St Irenaeus of Lyon In this, St Irenaeus is typical of the majority of Fathers. The relative authority of different elements of the hierarchy of the churches can be raised when necessary (either to make a positive point, as in St Irenaeus, about useful recourse in times of confusion; or to counter misappropriations of such authority when it arises, such as in the case of the east-west disputations of later centuries), but the theme simply does not hold a central place in the broad ecclesiological vision of the patristic sources. While in certain, restricted circles questions of personal, and later ecclesial primatial authority, would gain more traction as extrapolations of a “Petrine authority” amongst the Apostles, scholars and church authorities of both east and west have acknowledged that this was a later, and geographically restricted, phenomenon,[12] to which we can securely add that it has never represented the majority view of the patristic witness.

St Irenaeus of Lyon In this, St Irenaeus is typical of the majority of Fathers. The relative authority of different elements of the hierarchy of the churches can be raised when necessary (either to make a positive point, as in St Irenaeus, about useful recourse in times of confusion; or to counter misappropriations of such authority when it arises, such as in the case of the east-west disputations of later centuries), but the theme simply does not hold a central place in the broad ecclesiological vision of the patristic sources. While in certain, restricted circles questions of personal, and later ecclesial primatial authority, would gain more traction as extrapolations of a “Petrine authority” amongst the Apostles, scholars and church authorities of both east and west have acknowledged that this was a later, and geographically restricted, phenomenon,[12] to which we can securely add that it has never represented the majority view of the patristic witness.

It should, therefore, strike us as strange that “primacy and synodality” have become almost the central bywords of ecclesiological discussion in our contemporary milieu. It is always, or at least should always be, something of a red flag when a theme the Fathers themselves find secondary or even tertiary in importance becomes primary in discussions that, inevitably, seek to use patristic tradition to bolster the authority of claims they make. More so, when that re-orientation of priorities is then followed by a re-orientation of theological exegesis to accompany it. Yet this is precisely what we have witnessed in previous decades, and above all in the past thirty years: the centralization of “primacy” as an ecclesial concept has generated a re-orientation of Trinitarian relational discussion into the ecclesiological realm, as a means of giving substance to the erroneous and insupportable assertions of an ecclesiology that otherwise has no theological (and certainly no historical) merit.

Trinitarian Relations and Ecclesial Hierarchy

This is most explicitly the case when assertions of ‘primacy’ are substantiated by a parallelism of Church structures (namely, the episcopal hierarchy and the relations of authority within it) to the Persons of the Trinity and their relations one to another. To be clear at the outset, there is no patristic testimony whatsoever to the widespread modern concept, foundational to much “Trinitarian ecclesiology”, that the relations of the Church’s hierarchical structures are paralleled (whether ontologically, conceptually or iconically) to the eternal relations of Father, Son and Spirit. One strives in vain to find any patristic source who speaks in these terms, as inviting as they might sound to the modern ear. Yet the temptation of finding, in the Trinity-in-unity confession of the nature of God, a convenient parallel for describing the multiplicity-in-unity of human, ecclesial relations, has often proven too strong to resist. We saw this already explicitly stated in the Joint Commission’s Munich statement (1982), as well as shaping its continuation in Ravenna and other texts; we might point out that one of the most significant features of its 2016 plenary in Chieti was a re-examination of the concepts of “primacy and synodality” in terms that abolish this shaky “Trinitarian” foundation on which its earlier statements had been laid.

“A Trinitarian ecclesiology in extremis has been articulated: one in which the mis-application of the relations of the Trinity to the authority structures of the Church has reached the “logical” conclusion to which this rationalistic analysis leads—and has thereby produced theological-ecclesiological assertions never before heard in the history of Orthodox thought.”

Nevertheless, the temptation persists in internal Orthodox ecclesiological discussions. The present-day conflict between the ecclesiological assertions of scholars and hierarchs within the Patriarchate of Constantinople, which have evoked strong reactions amongst those of the other patriarchates and Local Churches, is the most poignant case in point. Let us set aside entirely, for the present discussion, the questions of territoriality and jurisdiction in certain parts of the world that are involved in much of our present-day inter-Orthodox disputation. While questions of territory, canonical jurisdiction and the sovereignty of patriarchates within the communion of all the Local Churches are, I hasten to clarify, entirely legitimate and important points of ecclesiological discussion, for our present analysis they are not relevant. What is relevant is how, in the midst of those discussions, a “Trinitarian ecclesiology” in extremis has been articulated: one in which the mis-application of the relations of the Trinity to the authority structures of the Church has reached the “logical” conclusion to which this rationalistic analysis leads—and has thereby produced theological-ecclesiological assertions never before heard in the history of Orthodox thought. Here I am not speaking of the now-infamous “first without equals” (primus sine paribus) claim for the See of Constantinople and its primatial occupant that has of late been asserted as a counter to the old axiom of “first among equals” (primus inter pares),[13] but rather the ecclesiological principles that have been asserted to ground and defend it: namely, that the Trinitarian “primacy” of the Father, in relation to the Son and Spirit, is embodied in one patriarchate (and more explicitly, personally in one patriarch) such that there is a unique authority that resides ontologically in one individual.[14]

Monarchy in the Holy Trinity

To comprehend the attractiveness of this logic to some, it is necessary to understand the Trinitarian principles it incorrectly takes up to substantiate it. As with so much that goes wrong in theological discussions over the course of history, it is not the starting points that are incorrect, but what is done once launching off from them. In the present matter, the Trinitarian confessions used in the maintenance of this ecclesiological vision are not incorrect; they are, rather, the basic, elemental confessions of an Orthodox Trinitarianism. What goes disastrously wrong is the mis-application of these to realms in which they simply do not apply.

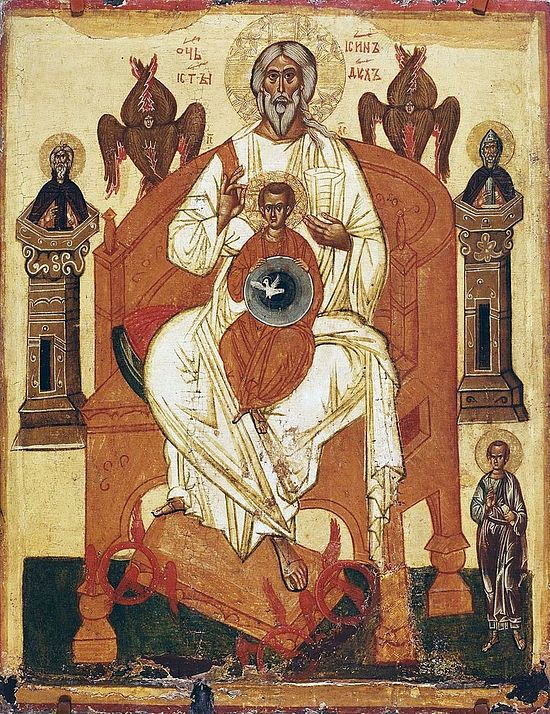

It is fundamental to the self-revelation of the One God that He is Father, Son and Spirit—a mystery we refer to as Trinity and which centuries of ever-refining theological articulation would come to describe specifically as a Trinity of three Persons, consubstantial, co-divine and co-eternal, existing in perfect and unalterable unity whilst maintaining, eternally, their personal distinctions perceived through their relations. The Son is eternally distinct from the Father through the precise, relational reality of His sonship—His “eternal begottenness” which makes Him eternally distinct from the Begettor. Likewise the Spirit is eternally distinct from the Father by His procession forth from the latter: the One Who is sent ever distinct from the One Who sends and, moreover, distinct from the Son in that the relation of procession is distinct from that of begetting. Each Person is thus distinct and unconfusable with the others, not by any distinction of divinity or ontology or even economy (all of which are explicitly rejected), but wholly by their distinguishable and non-interminglable relations.

Within these Trinitarian relations, the Father’s unique trait (setting Him eternally in distinction from the Son’s begottenness and the Spirit’s procession) is that He is the source (Gr. arche) of those relations. The Son’s “sonship” is defined by His being Son of the Father; the Spirit’s unique relational identity is defined by His being processed from the Father. The Father’s unique relational identity, in turn, is precisely that He is the source of the relations, and indeed the sole source—not in terms of temporal priority (the very phrase “eternally begotten”, which so befuddled Arius, is used precisely to eradicate the possibility of conceiving of a “before” or “after” in terms of these relations), but rather in the sole context of relational definition.[15] The Son is always the Son because He is always begotten of the Father; the Spirit is always the Spirit because He always proceeds from the Father; and the Father is always the Father because He always substantiates the sonship and procession of the other two Persons as Father, as sole “source”.[16] Thus the Trinitarian monarchicalism of the Father (mone + arche: “sole source”) becomes the standard means of articulating the relations of the co-eternal, co-equal Persons of God as Trinity from at least the time of the great Cappadocians.

There are a number of points in this traditional, patristic language of Trinity that should be noted in our present discussion. Firstly, the monarchy of the Father is necessarily as communal as it is relational. He cannot be Father without the Son, nor the One Who sends the Spirit if there is no Spirit being sent.[17] The relational, rather than ontological, nature of these identities requires the co-existence and co-eternity of all three. Similarly, the co-eternity of the Father’s identity as the sole arche of their relations, precisely because it is co-eternal in its relationality but not ontology (for there is only one ontological reality to the Trinity: there is one God), means there can be conceived no divine superiority of the Father. If the Father cannot be Father without the Son, then even though it is the Father who is the arche of that relation, the necessary co-eternity of both Persons, in order for either of them to be defined by their relations, means that in terms of their relational identities neither is precedent or greater than the other, even if we may be forced by the limitations of language to speak of ‘precedence’ at times, at the logical level.[18] The Son is not divine because He has received divinity from the Father (such would be an ontological, rather than relational, tri-unism); but similarly, the Father does not possess anything unto himself qua Father, by virtue of being the sole arche of their relations, except the characteristic of being source of the relation itself. The Father possesses no precedent divinity over the Son or Spirit, no precedent ‘authority’, no independent anything except His unique relational attribute of being, hypostatically, the Begettor of the Son and the One Who sends forth the Spirit.

The Problems of Tying the Relations of the Trinity to Ecclesial Structures

This basic description of classical patristic Trinitarian language now laid out, we are better situated to analyse the problems that arise when discussion of Trinitarian relations is applied to the structures of Church hierarchy and autonomy. As I mentioned before, the temptation to see in the Trinity, as unity-in-multiplicity of three Persons as one God, a convenient parallel for the relations of men to each other and of Church structures to other Church structures, is frequent. Surely, if man is a creation of God as Trinity, then it is in the Trinity that he will find some means of articulating who he himself is? And if the Church is the Body of God Who is Trinity, then surely it is in the Trinity that she will find definition for her internal life and function?

I have, however, also already pointed out that the most significant problem with this line of reasoning is that, despite its apparent attractiveness, it has no basis within the tradition of the Church herself. By one category of analysis, this ought to be enough, in itself, to dismiss this line of ecclesiological reasoning from the mindset of a Church which self-confessedly maintains “that faith which has been believed everywhere, always, by all”.[19] Yet expression and articulation of theological, as well as ecclesial, reality do indeed change over time, most certainly; so the deeper investigation must be into whether such novel claims are compatible with the theological vision of the Church, not solely with her historical articulations of that vision.

“When Christ famously prays to the Father, that ‘they may be one, even as we are one,’ we must not fail to hear these words in concert with that for which He prays next…”

The first place in which we discover an immediate incompatibility is in the very mis-application of Trinitarian expression to the Church, as if she were the Body of the Trinity and not the Body of Christ. There is simply no precedent in Orthodox thought for the modern-day assertion (oftentimes implicit in verbiage but explicit in the contours of the ecclesiology expressed[20]) that the Church is somehow a structural manifestation of Trinitarian relations.[21] Both St Paul and the innumerable patristic sources to follow him expressly assert that the Church is the Body, not of the Trinity, but of the second Person of the same; it is in Christ that humankind has access to the Trinity and is drawn into the unity of the Trinity—participating in that unity in, with and through its adoption into Christ and never as itself manifesting the divine relations of Father, Son and Spirit. When Christ famously prays to the Father, that they may be one, even as we are one (John 17.11/22, a text regularly used to support an improper “Trinitarian” ecclesiology), we must not fail to hear these words in concert with that for which He prays next: that man’s life be grafted wholly into His suffering and death and mission, that they may all be one, as Thou, Father, art in Me and I in Thee, that they also may be one in Us … I in them and Thou in Me, that they also may be made perfect in one; and that the world may know that Thou hast sent Me, and hast loved them as Thou hast loved Me (John 17.21, 23, emphasis added). Christ explicitly prays that the unity His disciples obtain should be an image, not of the eternal relational unity between Father, Son and Spirit, but precisely and emphatically the image of the unity of the incarnate Christ with His Father. Man shall never relate to the Father as the Son eternally relates to the Father (the property of eternal generation from the Father is never a property of the creature[22]); rather, Christ prays that they obtain unity in Him, and in this participate in His incarnate Sonship, drawn to the Father through the Father’s Spirit Whom Christ, their image and priest, sends. It is in this crucial distinction that we discover the foundation of so much that goes wrong in swaths of contemporary discussion.

Sermon on the Mount by Carl Bloch (1877). Photo: wikipedia

Sermon on the Mount by Carl Bloch (1877). Photo: wikipedia

The Church as the Body of Christ (which, even more than meaning the Body of the second Person of the Divine Trinity in His eternal reality, means explicitly the Body of His incarnate reality as the Christ crucified and risen), demands that the various aspects of the Church’s worldly structure likewise find their definition not in the Trinitarian relations writ large, but more specifically in the personal identity of the Son, and how He—incarnate, died and risen—relates to His Father and the Father’s Spirit. Men and women are grafted into the Church, united into the Body, after the image of the Son Who grafted all of humanity to Himself by taking flesh and becoming man. The Church is obedient unto the will of the Father, even as Christ was perfectly obedient to His Father’s will (cf. John 12.49, 14.31). The Church receives the Holy Spirit as the Son asks of His Father to send that Spirit (cf. John 15.26); and she receives the Father’s goodwill, that she inherit the Kingdom, by being united to the Son’s death, resurrection and ascension in glory.

It is entirely in the person of the incarnate Son that the Church finds her identity, articulating this ever more distinctively the more that she articulates clearly the Son’s relation to the Father and Spirit; but at no time does she find her subjective identity articulated either in the Trinity ‘as a whole’ (i.e. in the sum articulation of all the Trinitarian relations) or in either of the other Persons taken as the substance of her identity (as such she is never the :Body of the Father” or the “Body of the Spirit”, any more than she is the “Body of the Trinity”).

Yet it is precisely into such terrain that modern “Trinitarian” ecclesiology wanders. The centralization of “primacy” as an ecclesiological theme, mentioned earlier, has required a consonant emphasis on relationality (which takes as its starting point the Greek term koinonia, generally used to describe the relations between the Persons of the Trinity and usually translated into English as “communion”), in order to give substance to definitions of different structures in cooperation and organization. Focusing purely on the Church as the Body of Christ (as is found in the Scriptures and the Fathers) provides little in the way of theological fodder for extended consideration of this idea, since it is hardly possible to speak of the Son relating to Himself in varying ways (unless one is daring enough to wander into a kind of ecclesiological Nestorianism). It appears to be for this reason that the discussion therefore shifted, in twentieth-century discussions, precisely to the Church as relationally manifesting, in her various structures, the koinonia of relations of the Trinity—for there, at least, one is able to draw parallels between concretely distinct Persons in relation to another.[23]

“The Church as a structural embodiment of Trinitarian relations is an invention of the twentieth century: it has little relation to the Church as she has perceived her identity throughout history.”

And yet, to do so is to invent an ecclesiology that simply has no precedent in Orthodoxy. The Church as a structural embodiment of Trinitarian relations is an invention of the twentieth century: It has little relation (if that intentional pun may be pardoned) to the Church as she has perceived her identity throughout history. And the disaster of this is not only that it divorces such modern-day ecclesiological discussion from the whole of Christian tradition, but that it generates substantial problems not simply in Church life, but also, in an almost “retrospective” manner, in how she confesses the nature of God as Trinity. This modern ecclesiastical mis-appropriation of concepts retrospectively perverts Christianity’s most ancient and most fundamental theological confessions about God.

In claiming, for example, that one patriarch may be “first without equals” because the Church, in imaging the Trinity, images the relations of the Father, Son and Spirit, and the Father is “sole source” of the relations (and therefore the one patriarch who vicarially manifests the Father in this ecclesial hodgepodge must also have a unique role as ‘sole source’ of the authority of the other patriarchs and patriarchates[24]) not only introduces the quite extraordinary novelty of conceiving of any hierarch as ecclesial representation of the Father in relation to his brother-hierarchs,[25] but demonstrates that, in so doing, the authentic patristic monarchicalism of Trinitarian expression has also been modified. The whole emphasis of relational Trinitarian language, as expressed so clearly by St Gregory of Nyssa and the other Cappadocians amongst a host of others, is that the Father is not the source of authority in the Son or Spirit (nor of divinity, or power, or might, or eternity), and that while He is sole arche of their relations, the very fact of the co-eternity of those relations means there is nothing precedent in the Father, nothing sine paribus that He possesses except His personal identity as arche of the relational sonship of the Son and procession of the Spirit. He is not ‘responsible’ for their unity as a self-possessed, independent attribute (because without them bearing out their eternal relatedness there is no unity);[26] He is not ontologically “first” in a hierarchy (relational monarchy being utterly distinct from ontological hierarchy in theological discussions).[27]

To assert that one patriarch has an authority, within the communion of the hierarchy of all the Local Churches, because the Church manifests the relations of the Trinity which are personal and therefore must be tied to concrete Persons, and that in these personal relations that of the Father is the sole arche, is radically to misunderstand what this concept means to the Church Fathers. Not only is the entire parallelism between the Church and the Trinity incorrect, the conception of the Father as somehow the substantive foundation for a personal concept of primus sine paribus is also incorrect. If, in terms of the relations of the Persons of the Trinity, the Father is “without equals”, He is no more so than the Son and Holy Spirit are also “without equals”: each is a Person that cannot be conflated with the others. And just as the Father is not “first” but “sole” (mone),[28] inasmuch as He is the sole source of the relational identity of both Son and Spirit, similarly the Son is “sole,” not in being relational source, but in being sole Son; and the Spirit is “sole” in being sole Spirit. The Father’s identity as mone arche is not a primacy, nor a definition of hierarchy; for it to be applied to the Church’s hierarchy as paradigm is conceptually to damage both.

The Corrective: Christological Ecclesiology

There must be a correction made to this trend in ecclesiological thought, for we see in contemporary “Trinitarian ecclesiology” not only how badly wrong ecclesiological discussions can go when Trinitarian thought is misapplied to the Church’s structural identity (perverting her theological vision), but we see also the damage that this can cause in concrete terms of inter-Orthodox relations. The modern-day phenomenon of this novel ecclesiology, while being regularized in formal documents only by the Patriarchate of Constantinople (silently ignored by some other Local Churches, though thankfully in several cases explicitly rejected by others), has nevertheless found its way into the dogmatic conversations of scholars and pastors across the Orthodox world. It should be no real surprise that this coincides with the advent of schism and widening division between parts of that same world.

“The necessary corrective to this problem is to return ecclesiological discussions to what is their necessarily fundamental base: the nature of the Church as the Body of the incarnate, crucified, risen and glorified Jesus Christ.”

To be clear, an ecclesiology that seeks to define primacy and synodality in inter-ecclesial matters after the relational communion of the Persons of the Trinity will always fail the test of Orthodoxy. It is ahistorical, being a relatively recent innovation; it is a-catholic, being a tradition that does not represent the oikoumene of the Church in her universal manifestation; and above all it is a-theological, being a mis-application of Trinitarian concepts to realms in which they do not apply, disfiguring thereby both those realms and the Trinitarian vision of those who make this misapplication.

The necessary corrective to this problem is to return ecclesiological discussions to what is their necessarily fundamental base: the nature of the Church as the Body of the incarnate, crucified, risen and glorified Jesus Christ. It is this that Christ Himself taught, the Apostles preached, and the Fathers have maintained, and it is this that can reclaim the vacillations of modern discussion for the witness of Orthodoxy.

As Body of the Son, and the Son incarnate, the Church’s hierarchical structures are not defined by the relations of the Father, Son and Spirit, but by the relation of the Apostles to Christ, by Whom they were called out of the world and united to His life. Being grafted into Christ, the Apostles did not thereby become icons of the Father and Spirit, together with the Son, in terms of how they related one to the other; rather, they became personally engrafted into the Son’s obedience to the Father, through which they were called out of the disparate divisions of their human backgrounds (neither Jew nor Greek... Galatians 3.28) into unity in Christ. This Christological identity of the Church therefore meant that her life was bound up in the life of the Trinity, just as the Son is “One of the holy Trinity”, and therefore she is drawn into precisely the relations that the Son has with His Father and with the Holy Spirit; yet never into a confusion of persons and personal relations, any more than the Son’s relations with the other Persons of the Trinity are confused or inter-appropriated. Just as the Son’s identity is never confused by equating it with the identity of the Father, so His Body, the Church, never has her identity confused by misidentifying it with the Father or the Spirit.

The Church, and all her members, are drawn into the life of the incarnate Son; and this experience of becoming, of entering into the fulness of Life through being grafted into the Son’s incarnate and glorified human existence, is the quintessential characteristic of her identity. Those who “were many” are “made one body” (cf. 1 Corinthians 12.12), and in the centrality of the Eucharistic experience of the Church, the transformation of bread and wine, which undergo a “becoming” in their sanctification into the true Body and Blood of Christ, engender in man the becoming “one in Christ” (cf. Romans 12.5) that creates of the old man a new man and transforms death into life. In this, it should be obvious to us that the relational paradigm of the Church cannot be the manner in which the Son relates to the Father or the Spirit, for there is no “becoming” in those eternal relations, as there always is in ecclesial realities. Christ does not “become” one with the Father, but sanctified creation does become one in Christ—and it is precisely here, in the incarnate reality of the Son, that ecclesiology finds its relational substance and identity.[29]