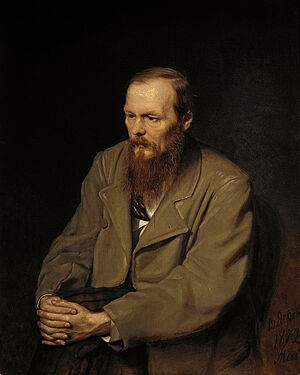

The great Russian author Feodor Dostoevsky found in St. Ambrose of Optina not only inspiration for the character of Elder Zosima in Brothers Karamazov—he also acquired peace and repentance in the famous elder’s tiny monastic cell. The following is an overview of Feodor Mikhailovich’s relationship to Elder Ambrose of Optina, who is celebrated today.

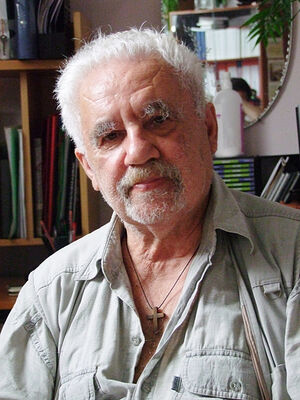

How close did Dostoevsky’s Zosima come to Ambrose of Optina? What did the famous author take away from his memorable meeting with St. Ambrose? The well-known Dostoevsky scholar Professor Sergei Vladimirovich Belov (June 23, 1936–November 7, 2019) discusses St. Ambrose as one of the important personages in Feodor Dostoevsky’s life in this chapter from his two-volume encyclopedia entitled, F. M. Dostoevsky and His Circles.1

Photo: A.Pospelov / Pravoslavie.ru

Photo: A.Pospelov / Pravoslavie.ru

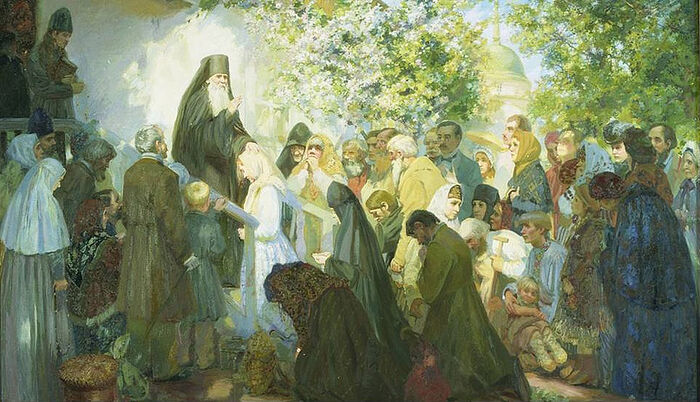

The writer’s wife, A. G. Dostoevskaya, recalls: “On 16 May 1878, our family was stricken with a terrible misfortune—our youngest son Lyosha [diminutive of Alexei] died <…>. In order to soothe Feodor Mikhailovich at least a little and distract him from his sad thoughts, I asked Vl[adimir]. S. Soloviev, who visited us during those days of our sorrow, to persuade Feodor Mikhailovich to go with him to Optina Hermitage, where Soloviev was planning to go that summer. It was Feodor Mikhailovich’s longtime dream to visit Optina Hermitage….”

Optina Hermitage is an ancient monastery founded, according to tradition, back in the fourteenth century near the ancient town of Kozelsk in the Kaluga region. This monastery gave birth to a particular type of Russian monasticism—eldership. Dostoevsky went to Optina Monastery with Vl. S. Soloviev from the 23rd to 29th of June, 1878.

“Feoder Mikhailovich returned from Optina Hermitage as if at peace and significantly calmed,” A. G. Dostoevskaya continues in her “Recollections”, “and told me a lot about the customs of Optina Monastery, where he spent two days and nights. He saw the famous elder, Fr. Ambrose, three times: once in a crowd of people and twice alone, and he came away from these talks with a deep and penetrating impression. When Feodor Mikhailovich told the elder about our misfortune and about my grief, which manifested itself far too stormily, the elder asked him whether I am a believer. When Feodor Mikhailovich answered in the affirmative, the elder asked him to send me his blessing, as well as those words that Elder Zosima would later say to the grieving mother in his novel… From Feodor Mikhailovich’s stories it could be seen what a profound seer of hearts and clairvoyant was this elder, respected by all.”

In “Notations to the works of F. M. Dostoevsky,” A. G. Dostoevskaya, citing the words of Zosima from Brothers Karamazov: “I’ll pray for you, mother, I’ll pray for you, I’ll remember your sorrow in my prayers, and I’ll pray for the health of your husband,” writes, “These are the words that Feodor Mikhailovich passed on to me when he returned in 1878 from Optina Hermitage. There he talked with Elder Ambrose and told him about how we grieve and weep over our boy who recently died. Elder Ambrose promised Feodor Mikhailovich that he would “remember Alyosha in prayer” and pray about “my sadness”, and that he would also pray for the health of us and our children. Feodor Mikhailovich was deeply moved by his talk with the elder and his promise to pray for us.”

In A. G. Dostoevskaya’s journal there are words from Elder Ambrose to the writer, written down by her from her husband’s words: “There are children who are destined from above to die either in their mother’s womb, or in early childhood—these are children who were conceived on the eve of feasts of the Mother of God.”2 (ИРЛИ. № 30766).

St. Ambrose of Optina Elder Ambrose served to a great extent as the prototype of Elder Zosima in Brothers Karamazov, and the description of the arrangement of the skete and Zosima’s cell and surroundings was based on Optina Monastery. For example, St. Ambrose’s cell is thus described in one popular brochure about his life: “The little house had a small porch, the door had a window hung with muslin on the inside and opened into a low-lit entryway; to the right of the entryway was a reception room. Its walls were hung with portraits of various ascetical monks of the past century, and several bishops. The fore-corner was filled with large icons, and an oil votive lamp burned before them. A sofa, several armchairs, and a bookcase with spiritual books completed the interior.”

St. Ambrose of Optina Elder Ambrose served to a great extent as the prototype of Elder Zosima in Brothers Karamazov, and the description of the arrangement of the skete and Zosima’s cell and surroundings was based on Optina Monastery. For example, St. Ambrose’s cell is thus described in one popular brochure about his life: “The little house had a small porch, the door had a window hung with muslin on the inside and opened into a low-lit entryway; to the right of the entryway was a reception room. Its walls were hung with portraits of various ascetical monks of the past century, and several bishops. The fore-corner was filled with large icons, and an oil votive lamp burned before them. A sofa, several armchairs, and a bookcase with spiritual books completed the interior.”

The image of Elder Zosima thundered across Russia; however, years after Dostoevsky’s death, the writer and philosopher Konstantine Leontiev, whom Elder Ambrose had secretly tonsured a monk, wrote to the philosopher V. V. Rozanov on April 12, 1891: “But I fervently pray to God that you would quickly outgrow Dostoevsky with his “harmonies”, which will never be, and in fact aren’t needed. His monasticism is invented. And the teachings of Zosima are false; and the entire style of his discussions in false.” Leontiev gives an even more cutting review of Zosima as compared to Elder Ambrose in his letter to V. V. Rozanov dated May 8, 1891: “In Optina they do not recognize Brothers Karamazov as correct Orthodox teaching, and Elder Zosima does not resemble Elder Ambrose at all, neither in teaching nor in character. Dostoevsky only described his outward appearance, but he made him say what he would never say, and not in the style that Ambrose uses to express himself. Fr. Ambrose has first of all Church mysticism, and only then, applied morals. Fr. Zosima has (through whose lips Feodor Mikhailovich himself spoke!) first of all moral, ‘love’, and so on… Well, his mysticism is very weak. Don’t believe him when he boasts that he knows monasticism; he only knows well his own preaching of love, and no more! He was only in Optina two or three days, and no more! … ‘Love’ (or more simply and clearly put, kindness, mercy, justice) needs to be preached, for it is scarce among people and is easily extinguished in them, but one shouldn’t prophesy its coming reign on earth. This is psychologically and realistically impossible and theologically impermissible, for it was condemned a long time ago by the Church as a kind of heresy…”

In this correspondence with V.V. Rozanov, Konstatine Leontiev cites a letter to him from Vladimir Soloviev in which the latter writes extremely cuttingly about Dostoevsky’s religiosity, essentially corresponding to Leontiev’s own expression on it: “Dostoevsky fervently believed in the existence of religion and often observed it through a telescope, as at a distant object, but he was never able to actually step onto religious ground.”

Under the influence of Konstantine Leontev’s letters, many Dostoevsky scholars consider that the real Elder Ambrose externally served as Zosima’s prototype, while Zosima’s entire teaching was based upon the works of St. Tikhon of Zadonsk. Truly, the famous St. Tikhon of Zadonsk, who lived in the eighteenth century, had long before attracted Dostoevsky’s attention. In his letter to his friend the poet A. N. Maikov dated March 25 (April 6), 1870, Dostoevsky remarks, “In in second novella I would like to display Tikhon of Zadonsk as the main figure… And who knows but I’ll bring out a grand and positive figure… How do we know? Perhaps it is precisely Tikhon who comprises our positive Russian type, for whom our literature is searching…”

But does Zosima really resemble Ambrose only externally and did the Optina brothers really not accept as “theirs” either Brothers Karamazov or Zosima? Why did Leontev call Dostoevsky’s Christianity “rose-colored”, and what was that letter of Vladimir Soloviev, who earlier wrote the complete opposite about the writer’s religiosity? However, before we can answer these questions, we will point out that Fr. Ambrose belonged to the “St. Seraphim” trend in Russian religious thought, which differed from the main Byzantine-Muscovite trend, just as St. Nilus of Sora differed from St. Joseph of Volokolamsk. The nearly forgotten movement of St. Nilus of Sora was reborn in the eighteenth century through three men: St. Paisius Velichkovsky (1722–1794), St. Tikhon of Zadonsk (1724–1783), and St. Seraphim of Sarov (1759–1833). Optina Hermitage became the unofficial center of Orthodox culture and spiritual life—the center where the spiritual values of St. Nilus’s teachings were most plainly revealed. Dostoevsky wrote very precisely about the rebirth of eldership in Brothers Karamazov: “It was reborn among us again from the end of the last century by one of the great podvizhniks (as they call him), Paisius Velichkovsky and his disciples, but even today, after nearly one hundred years, it exists in in very few monasteries and has even been subjected at times to near persecution as if it were an unprecedented novelty in Russia. It has especially flourished in our Rus’ in one well known monastery, Optina of Kozelsk.” Let us also note here that the followers of St. Paisius Velichkovsky had brought back to Russia what was nearly forgotten by that time—the ascetic and mystical works of the ancient fathers of the Church.

Feodor Dostoevsky Fr. Ambrose was a disciple of Fr. Leo, who died in 1842, and of Fr. Macarius, who died in 1860; both Fr. Leo and Fr. Macarius were indirect disciples of St. Paisius.3 Considering that in Dostoevsky’s library was the book, Life of Optina Elder Hieromonk Leonid (in Schema Leo), then we can almost surely suppose that before going to Optina Monastery and before creating the image of Zosima, Dostoevsky studied the entire history of Optina Monastery, knew about the struggle between the “acquirers” and the “non-acquirers”—St. Joseph of Volokolamsk and St. Nilus of Sora—in the Russian Church, and knew that St. Ambrose belonged to the followers of St. Nilus of Sora and St. Paisius Velichkovsky; that is, to the “St. Seraphim” trend in Russian religious thought.

Feodor Dostoevsky Fr. Ambrose was a disciple of Fr. Leo, who died in 1842, and of Fr. Macarius, who died in 1860; both Fr. Leo and Fr. Macarius were indirect disciples of St. Paisius.3 Considering that in Dostoevsky’s library was the book, Life of Optina Elder Hieromonk Leonid (in Schema Leo), then we can almost surely suppose that before going to Optina Monastery and before creating the image of Zosima, Dostoevsky studied the entire history of Optina Monastery, knew about the struggle between the “acquirers” and the “non-acquirers”—St. Joseph of Volokolamsk and St. Nilus of Sora—in the Russian Church, and knew that St. Ambrose belonged to the followers of St. Nilus of Sora and St. Paisius Velichkovsky; that is, to the “St. Seraphim” trend in Russian religious thought.

So, these are the main thoughts in St. Ambrose’s teaching reflected in Brothers Karamazov. First of all, all the teachings of Elder Ambrose are penetrated with loving humility. “After all, humility,” St. Ambrose notes in one of his letters, “consists in when a person sees himself as one of the worst of all, not only of people, but even of dumb beasts, and even of the evil spirits.” Zosima teaches: “Man, do not be haughty over the animals—they are sinless, and you with your grandeur rot the earth with your presence on it… Your thoughts may cause doubts, especially when you see people’s sins, and you’ll ask yourself: ‘Should I take them by force, or by humble love?’ Always resolve to yourself: ‘I will take them by humble love.’ Resolve to do this once and for all and you will be able to win over the whole world. Loving humility is a terrible force, stronger than all others, and there is none other like it.” Following the Gospel command to abstain from judging others, Zosima teaches: “Especially remember that you cannot be anyone’s judge. For a criminal cannot be a judge on earth until that same judge recognizes that he is just the same sort of criminal as the one standing before him, and that perhaps he himself is mostly to blame for that very crime committed by the criminal standing before him.” And here are the words of St. Ambrose: “Only strive to live according the Gospel commandments, and first of all never judge anyone for anything, so that you yourself will not be judged.

Like St. Nilus of Sora, St. Ambrose taught to hold to the middle path in spiritual life, with a sense of measure: “The middle measure receives approval everywhere and in everything.” One of St. Ambrose’s letters to laypeople is even titled that way: “There should be measure in fasting.” That is why Monk Ferapont in Brothers Karamazov, a fanatic and nineteenth century “Josephite”, judges Zosima for his counsel to a monk troubled by visions of evil spirits to take medicines. Incidentally, one of St. Ambrose’s letters to laypeople is also called: “Getting medical treatment is not a sin.” “All is from God,” write St. Ambrose, “both medicines and doctors. And it is not a sin for a man to have recourse to medical treatment. At the same time, the sick person should not place all his hope for recovery on only the doctors and treatments, forgetting that everythig depends on the all-good and omnipotent God, Who alone makes one to live or die, as He deigns.”

The problem of suffering and the common responsibility of each person for all and all for everyone is one of the central issues in the teachings of Ambrose and Zosima. “Sometimes an innocent person is sent sufferings,” St. Ambrose taught, “so that according to Christ’s example, he would suffer for others… Having perfect love means suffering for your neighbor.” Zosima is close to this: “Strive to love your neighbors actively and tirelessly. To the measure that you will progress in love, you will be convinced of the existence of God and the immortality of your own souls. If you reach complete self-sacrifice in love of neighbor, then without a doubt you will come to believe, and no doubts will even be able to enter your soul.”

The question of freedom, also one of the most important questions in the teachings of Ambrose and Zosima, is solved by both of them in the same way: True freedom leads to the unity of human freedom and divine truth. One of St. Ambrose’s letters to laypeople, which is titled, “Man is given freedom. How to be saved,” begins with the following discussion: “God has given man freedom, intellect, and the law of revelation; and this freedom is tested as to how the person will use it.”

Significantly more examples of such concurrence of thought in the teachings of St. Ambrose in Elder Zosima could be cited; however enough has been said to bring us to the conclusion that all these thoughts were to varying degrees common to all the followers of St. Nilus of Sora, including for St. Tikhon of Zadonsk and St. Ambrose. (We must note that St. Ambrose himself directly participated in the publication of the works of Sts. Nilus of Sora, Tikhon of Zadonsk, and Paisius Velichkovsky). Let us take a brief look at the themes belonging exclusively to Ambrose, Zosima, and to Dostoevsky himself as contemporaries. From this point of view we can compare Dostoevsky’s exposé of nihilism, atheism, and socialism in Diary of a Writer with St. Ambrose’s letter dated March 14, 1881 concerning the murder of Emperor Alexander II, which is called, “Nihilists and regicides are the forerunners of Antichrist”: “I don’t know what to write to you about the horrible present times and the pitiful state of affairs in Russia… The spirit of antichrist has worked through his forerunners since apostolic times… At first it worked through various heretics… then it worked cunningly through educated Masons; and finally, now through educated nihilists it has begun to act brazenly and crudely, beyond measure.” Quite telling in this case is the fact that one of St. Ambrose’s dreams, which he talked about in letters to laypeople, is startlingly reminiscent of Raskolnikov’s prison dream [in Crime and Punishment].

Professor Sergei Vladimirovich Belov We could also compare the anti-Catholic character of the “Legend of the Grand Inquisitor” in Brothers Karamazov with the teachings of the Optina elders and in part of St. Ambrose. Fr. Paisius, Elder Zosima’s faithful disciple, says in Brothers Karamazov: “Please understand that it is not the Church that turns into government. That is Rome and its dream. That’s the third diabolic temptation! But to the contrary, the government turns into a church, is raised up to a church and becomes a church on this earth.” One of St. Ambrose’s letters, which he titled, “To a Roman Catholic married to an Orthodox woman, on the wrongness of Catholicism,” begins thus: “In the Gospel teaching love is preached; but the Roman Catholic priests inculcate in their parishioners from the earliest age disdain and hatred for those of other faiths, especially the Orthodox. The Lord says in the Gospel: “My kingdom is not of this world”, but the Roman popes desired an earthly kingdom as well.” These same thoughts can be found in the teachings of other Optina elders.

Professor Sergei Vladimirovich Belov We could also compare the anti-Catholic character of the “Legend of the Grand Inquisitor” in Brothers Karamazov with the teachings of the Optina elders and in part of St. Ambrose. Fr. Paisius, Elder Zosima’s faithful disciple, says in Brothers Karamazov: “Please understand that it is not the Church that turns into government. That is Rome and its dream. That’s the third diabolic temptation! But to the contrary, the government turns into a church, is raised up to a church and becomes a church on this earth.” One of St. Ambrose’s letters, which he titled, “To a Roman Catholic married to an Orthodox woman, on the wrongness of Catholicism,” begins thus: “In the Gospel teaching love is preached; but the Roman Catholic priests inculcate in their parishioners from the earliest age disdain and hatred for those of other faiths, especially the Orthodox. The Lord says in the Gospel: “My kingdom is not of this world”, but the Roman popes desired an earthly kingdom as well.” These same thoughts can be found in the teachings of other Optina elders.

Dostoevsky as if also foresaw St. Ambrose’s “post mortem fate”, which he links with the “post mortem fate” of Zosima. One can compare the chapter entitled, “A Noxious Odor” in the seventh chapter of Brothers Karamazov with Ambrose’s words, which Dostoevsky could have heard in Optina Monastery, because Ambrose repeated them often: “I received much glory from people during my life, and that is why I’ll emit a stench.” According to the Russian folk belief, the bodies of the righteous are considered not subject to corruption. In the chapter, “A Noxious Odor” Dostoevsky warred with this approach to religion bordering on superstition (it has to be noted that St. Joseph of Volokolamsk criticized St. Nilus of Sora for leaving out mention of miracles in the Saints’ Lives he published), as if practically proving Zosima’s testament to his flock: “Children, do not seek miracles; miracles kill faith.” And here is what an eye-witness to St. Ambrose’s final days said: “At the beginning of his pre-death illness, Elder Ambrose asked one nun to read him the book of Job. In it, incidentally, it is said that even the righteous man’s wife ran away from the stench of his wounds. By this example, as it is thought, the elder forewarned that something like this would happen to him after his death. And truly, a heavy smell of death came from the elder soon after his repose. In fact, he had told his cell attendant Fr. Joseph straightforwardly about this long before. At the latter’s question, “Why so?” the humble elder said, “This will happen to me because during my life I accepted too many unmerited honors.” At the same time, we can’t exclude the possibility that Dostoevsky had some influence on St. Ambrose; that is, St. Ambrose might have foretold his own “post mortem fate” after reading Brothers Karamazov.

St. Ambrose of Optina But it’s true, there are themes in Zosima that differ from the entire teaching of St. Ambrose. Cosmic mysticism, the absence of dogmatism in faith, an exalted love for everything earthly, the predominance of teaching about man and the world over teaching about God, the absence of the fear of sin, the cult of Mother Earth—these are the novelties that Dostoevsky introduced into the image of Zosima in comparison with his real-life prototype—the Optina elder Ambrose. Let us recall Zosima’s famous words: “Love falling to the ground and kissing it. Kiss the ground and tirelessly, insatiably love, love everyone, love everything, seek this exaltation and ecstasy. Soak the earth with your tears of joy and love these tears of yours.”

St. Ambrose of Optina But it’s true, there are themes in Zosima that differ from the entire teaching of St. Ambrose. Cosmic mysticism, the absence of dogmatism in faith, an exalted love for everything earthly, the predominance of teaching about man and the world over teaching about God, the absence of the fear of sin, the cult of Mother Earth—these are the novelties that Dostoevsky introduced into the image of Zosima in comparison with his real-life prototype—the Optina elder Ambrose. Let us recall Zosima’s famous words: “Love falling to the ground and kissing it. Kiss the ground and tirelessly, insatiably love, love everyone, love everything, seek this exaltation and ecstasy. Soak the earth with your tears of joy and love these tears of yours.”

So, was Konstantine Leontev correct when he wrote that “Elder Zosima does not resemble Fr. Ambrose at all in his teaching or character”? In his book on Dostoevsky, N. A. Berdayev notes: “Not only conservative Catholicism but also conservative Orthodoxy should run into difficulties in accepting Dostoevsky as their own… Dostoevsky’s Christianity is not historical but apocalyptic Christianity… Zosima is not the image of traditional eldership. He does not resemble the Optina elder Ambrose."

Nevertheless, closest to the truth is George Florovsky, when he notes that the image of Zosima is essentially a continuation and rebirth of the traditions of St. Nilus of Sora (which Dostoevsky saw in the works of St. Tikhon of Zadonsk), in the person of St. Ambrose, the works of St. Isaac the Syrian, and a prophetic synthesis of them all. In this sense, the image of Zosima truly did not always fit into the traditional Orthodox monasticism of Dostoevsky’s time, if the word “traditional” means only the predominating “Josephite” tradition.

When comparing Konstantine Leontev and Dostoevsky, we are closer to Dostoevsky. Love and humaneness are not “rose-coloredness”. Dostoevsky in the elders “was guessing at something better”, as he did in certain other things. Of course, both Ferapont and the “elder who was subject to corruption” are not really even a stylization but they are somewhat romanticized. This for Dostoevsky was lawful and unavoidable—after all, he had his own particular realism. And we have to read it all through truthfully, and not through Leontiev’s rather dry prose. Leontiev himself also has the characteristics of one of the Russian elders. But he did not get to the true, that is, the grace-filled charismatic spirituality, but rather was simply an intelligent and ardent (as we can see further on in the story of Vladimir Soloviev’s letter, he was at times a little too ardent) son of his own people.

V. V. Rozanov in his time precisely noticed: “If this did not answer to the type of Russian monasticism of the eighteenth to nineteenth centuries (Leontev’s words”, then perhaps, and even probably, it answered to the type of monasticism of the fourth to ninth centuries.” Dostoevsky is in any case actually closer to St. John Chrysostom (and precisely in his social motives), than Constantine Leontev. V. V. Rozanov adds: “All of Russia read Brothers Karamazov and examined the image of Elder Zosima. The “Russian monk” (Dostoevsky’s term) appeared as a familiar and charming image in the eyes of all Russia, even in its non-religious parts.”

Well, then what to do with Vladimir Soloviev’s letter to Konstantine Leontev, the sense of which so diametrically opposes the earlier written “Three speeches in memoriam of Dostoevsky, by Vladimir Soloviev” (1881–1883) and his own “Annotation in defense of Dostoevsky against the accusation of ‘new Christianity’ (1884) concerning Konstantine Leontiev’s work, “Our new Christians…”, in which Soloviev to the contrary affirmed that Dostoevsky always stood on “truly religious ground”? R. A. Galtseva and I. B. Rodnyanskaya quite justly write that “apparently the information coming from Leontiev requires caution in light of the fact that due to his characteristic strange grip in any argument of principle, he often gives facts and opinions different emphasis”; and further: “Similar cases of this force us to suppose that Leontiev is just as arbitrary when he relates Soloviev’s contemptuous comment on Dostoevsky’s religiosity, supposedly contained in one letter from Soloviev, which Leontiev obviously cites from memory and without indicating the date.”

Why then didn’t Leontiev accept Zosima? Well, first of all because he himself was a convinced “Josephite” (it is no coincidence that Leontiev called Dostoevsky’s Christianity “rose-colored”; and N. A. Berdyaev in his book, Konstantine Leontiev, [Paris, 1926, p. 222] in turn called Leontiev’s Christianity “black Christianity”). We can hardly agree with Leontiev’s assertion that “in Optina, they don’t accept Brothers Karamazov as a correct Orthodox work.” Truly, Dostoevsky portrayed, or more precisely, projected the Optina elders, their “St. Seraphim trend”—that is, the tradition of St. Nilus of Sora—into the future. By force of his artistic clairvoyance Dostoevsky guessed at and recognized this St. Seraphim trend in Russian piety and prophetically continued its marked line. However, as we have shown, Konstantine Leontiev was not right when he asserted that “Elder Zosima bears no resemblance to Fr. Ambrose, neither his character nor his teaching.” The image of Zosima is a collective literary image, an “ideal” or “idealized” portrait. In this image are found the reflections and teachings of St. Nilus of Sora, St. Tikhon of Zadonsk, and the book, Life and Labors of Elder Schemamonk Zosima, as well as Dostoevsky’s personal acquaintance with Elder Ambrose. Nevertheless, significantly more of Elder Ambrose went into the image of Zosima than a mere external likeness.

From Feodor Dostoevsky and His Circles, v. 1, pp. 40–45.