Venerable Edburga of Bicester

Commemorated: July 18/31

St. Edburga (Edburgh, Eadburgh) was one of several saintly daughters of the pagan King Penda of Mercia, who ruled between 626 and 655. Though he was a ferocious warrior responsible for the martyrdom of several Christian kings of other kingdoms, he tolerated Christian converts in his domain as long as they practiced their faith. Little is known about St. Edburga. She was born in about 620 and was a nun most of her life. The holy maiden labored with her sister Edith, probably founding a monastery in Aylesbury in Buckinghamshire (then in Mercia) or, according to another version, in Adderbury (“Edburgh's burgh”) thirty miles away in what is now Oxfordshire. Later sources call her an abbess. It is possible that St. Osyth of Chich was St. Edburga’s niece and disciple. St. Edburga reposed peacefully in c. 650 aged about thirty. Her name occurs in some early litanies and probably in the Durham Liber Vitae (“Book of Life”).

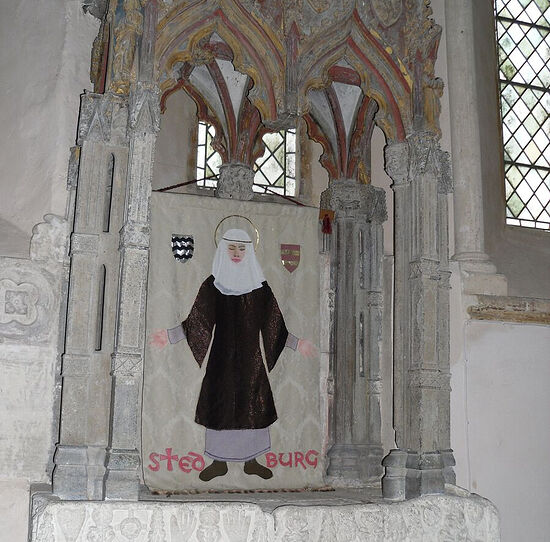

Part of St. Edburga's shrine at St. Michael's Church in Stanton Harcourt, Oxon (photo by Irina Lapa)

Part of St. Edburga's shrine at St. Michael's Church in Stanton Harcourt, Oxon (photo by Irina Lapa)

In 1182, her relics were translated from Adderbury to the newly-opened Catholic Augustine Priory in Bicester (in Oxfordshire), dedicated to Our Lady and St. Edburga. From that time on St. Edburga’s Purbeck marble shrine was visited by numerous pilgrims. However, in 1500 on the decree of the Pope of Rome, a large portion of her relics was transferred to Flanders, and the remainder was believed to have been hidden during the Reformation that came soon afterward. Since Bicester Priory was never rich, it was one of the first to be closed by Henry VIII.

St. Edburg's Church in Bicester, Oxon (photo by Jon S, Geograph.org.uk)

St. Edburg's Church in Bicester, Oxon (photo by Jon S, Geograph.org.uk)

Only a few remains of Bicester Priory survive in the center of the historic market town of Bicester in the northeast of Oxfordshire, but the town has a medieval Anglican parish church dedicated to St. Edburga. The present church was first mentioned in 1104. The priory supplied this town church with priests for centuries and enlarged it substantially, being its patron. Almost all the medieval stained-glass windows were lost during lightning strikes in 1765, but the church has some fine Victorian windows. In the Victorian era the church was restored, and a wooden screen with painted decorations added. The parish commemorates its patron-saint annually. The first wooden minster church had been founded in this settlement as early as the mid-seventh century, probably by followers of St. Birinus. Archeological excavations revealed the existence of a large Saxon cemetery. In the Middle Ages, there used to be St. Edburg’s healing well in Bicester. One of this rapidly developing town’s primary schools is called St. Edburg’s.

In 2011, archeologists thought that they had found some of St. Edburga’s relics under an apartment block in Bicester. According to media reports, workers discovered a lead container with human bones and remains of clothes in it. There were also thirteen skeletons, presumably from the fourteenth century, beside it. The version that these were the bones of local monks was proposed. There were plans to carbon-date the remains to ascertain at what time those people lived. Archeologists were positive that the bones had lain on the site of the former priory church’s transept.

Inside St. Michael's Church in Stanton Harcourt, Oxon (photo by Irina Lapa) However, our saint is best remembered in the Oxfordshire village of Stanton Harcourt fifteen miles away, where the Norman St. Michael’s Church still has part of her splendid shrine which is visited by pilgrims. This shrine base (canopy) dates to 1320 or earlier. In 1537, Simon Harcourt, the Sheriff of Oxford who was responsible for the demolition of the Priory Church in Bicester, saved this part of the saint’s shrine by moving it from Bicester to Stanton Harcourt so it could be used as a Paschal sepulcher. The chest containing St. Edburga’s relics would originally have stood on top of it. The visible lower section is not the original base but part of a later tomb. This treasure is in the chancel’s north wall by the High Altar. Its identity was discovered in 1935 by an expert in heraldry. Simon Harcourt’s tomb is in the church’s south transept.

Inside St. Michael's Church in Stanton Harcourt, Oxon (photo by Irina Lapa) However, our saint is best remembered in the Oxfordshire village of Stanton Harcourt fifteen miles away, where the Norman St. Michael’s Church still has part of her splendid shrine which is visited by pilgrims. This shrine base (canopy) dates to 1320 or earlier. In 1537, Simon Harcourt, the Sheriff of Oxford who was responsible for the demolition of the Priory Church in Bicester, saved this part of the saint’s shrine by moving it from Bicester to Stanton Harcourt so it could be used as a Paschal sepulcher. The chest containing St. Edburga’s relics would originally have stood on top of it. The visible lower section is not the original base but part of a later tomb. This treasure is in the chancel’s north wall by the High Altar. Its identity was discovered in 1935 by an expert in heraldry. Simon Harcourt’s tomb is in the church’s south transept.

Image of Queen Adeliza or St. Etheldreda of Ely on the screen of St. Michael's Church, Stanton Harcourt (provided by Gillian Salway) St. Michael’s Church has the oldest surviving wooden rood screen (roughly an analogue of the Orthodox iconostasis) in the country, which separates the chancel from the nave. After the Reformation, most churches did away with these, but there are some surviving. It is so old that it predates St. Edburga’s shrine base. There are two painted panels on the right of the screen which escaped the attention of Puritans. A darkish painting of a woman in a nun’s habit and a crown stands out—the best guess is that it is Queen Adeliza (c. 1103–1151), King Henry I’s second wife, who owned the manor of Stanton Harcourt and retired to Affligen Abbey (Brabant) in later life. Other guesses are that it might be St. Etheldreda of Ely or St. Frideswide of Oxford. It was Queen Adeliza who had this church built in 1130, though. The church retains features of the Norman, Perpendicular and Early English Gothic styles. London’s Tate Gallery has a drawing by the great artist J.M.W. Turner (1775–1851), “Interior of St. Michael’s Church, Stanton Harcourt, Oxfordshire, Looking East.”

Image of Queen Adeliza or St. Etheldreda of Ely on the screen of St. Michael's Church, Stanton Harcourt (provided by Gillian Salway) St. Michael’s Church has the oldest surviving wooden rood screen (roughly an analogue of the Orthodox iconostasis) in the country, which separates the chancel from the nave. After the Reformation, most churches did away with these, but there are some surviving. It is so old that it predates St. Edburga’s shrine base. There are two painted panels on the right of the screen which escaped the attention of Puritans. A darkish painting of a woman in a nun’s habit and a crown stands out—the best guess is that it is Queen Adeliza (c. 1103–1151), King Henry I’s second wife, who owned the manor of Stanton Harcourt and retired to Affligen Abbey (Brabant) in later life. Other guesses are that it might be St. Etheldreda of Ely or St. Frideswide of Oxford. It was Queen Adeliza who had this church built in 1130, though. The church retains features of the Norman, Perpendicular and Early English Gothic styles. London’s Tate Gallery has a drawing by the great artist J.M.W. Turner (1775–1851), “Interior of St. Michael’s Church, Stanton Harcourt, Oxfordshire, Looking East.”

St. Michael's Church in Stanton Harcourt, Oxon (photo - Irina Lapa)

St. Michael's Church in Stanton Harcourt, Oxon (photo - Irina Lapa)

The village has been closely linked to the Harcourt family for about 900 years. The family has a manor with its own chapel here.

Church of Sts. Mary and Edburga in Stratton Audley, Oxon (provided by the parish administrator)

Church of Sts. Mary and Edburga in Stratton Audley, Oxon (provided by the parish administrator)

The parish church in the village of Stratton Audley in north-east Oxfordshire is dedicated to St. Mary and St. Edburga (twelfth century with later additions). St. Edburga of Bicester should not be confused with several other early English saints with the same name.

Inside the Church of Sts. Mary and Edburga in Stratton Audley, Oxon (provided by the parish administrator)

Inside the Church of Sts. Mary and Edburga in Stratton Audley, Oxon (provided by the parish administrator)

Venerable Sexburga of Minster-in-Sheppey, Abbess of Ely

Commemorated: July 6/19

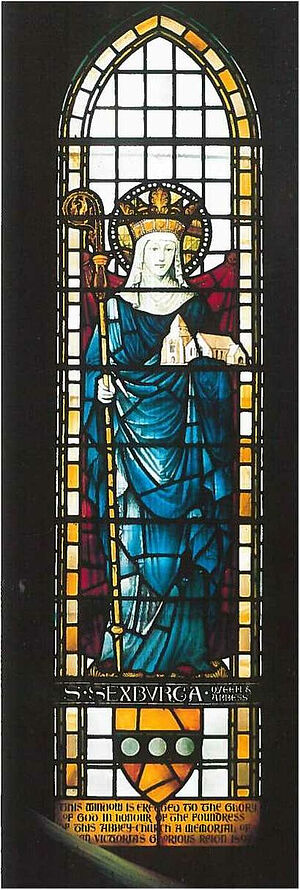

Stained glass image of St. Sexburgh (kindly provided by the congregation of Minster Abbey from West Sheppey Parish) St. Sexburga (Seaxburgh, Saxburga), who was born in about 625 and reposed in around 700, was the oldest daughter of the righteous King Anna of East Anglia (ruled c. 635-654), and a sister of Sts. Etheldreda of Ely, Ethelburgh of Faremoutiers (Gaul), Withburgh of Dereham, a sister or cousin of St. Jurmin of Blythburgh and a half-sister of St. Sethrida of Faremoutiers. There are several late versions of her Life, one of which was written in the early twelfth century. She married Erconbert, King of Kent (ruled 640–664), becoming the mother of two sons who later succeeded him (Egbert I and Hlothere), and two daughters—Sts. Ermenhild and Ercongotha. As Queen Consort of Kent, she was noted for her piety and humility, and built the convent of Minster on the Isle of Sheppey and probably a church at Milton Regis near Sittingbourne. Minster would become very famous—nuns and maidens would pray and attend services there day and night.

Stained glass image of St. Sexburgh (kindly provided by the congregation of Minster Abbey from West Sheppey Parish) St. Sexburga (Seaxburgh, Saxburga), who was born in about 625 and reposed in around 700, was the oldest daughter of the righteous King Anna of East Anglia (ruled c. 635-654), and a sister of Sts. Etheldreda of Ely, Ethelburgh of Faremoutiers (Gaul), Withburgh of Dereham, a sister or cousin of St. Jurmin of Blythburgh and a half-sister of St. Sethrida of Faremoutiers. There are several late versions of her Life, one of which was written in the early twelfth century. She married Erconbert, King of Kent (ruled 640–664), becoming the mother of two sons who later succeeded him (Egbert I and Hlothere), and two daughters—Sts. Ermenhild and Ercongotha. As Queen Consort of Kent, she was noted for her piety and humility, and built the convent of Minster on the Isle of Sheppey and probably a church at Milton Regis near Sittingbourne. Minster would become very famous—nuns and maidens would pray and attend services there day and night.

According to the Venerable Bede who wrote about this royal couple in his History of the English Church and People (b. III), Erconbert was the first English king to order that all pagan idols be destroyed and for Lent to be observed by his subjects. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle said that he was the first ruler to establish the Paschal celebration across his kingdom. He appointed St. Deusdedit, the first native Saxon to serve as Archbishop of Canterbury. Widowed in 664 (Erconbert died during the plague), St. Sexburga served as regent to her young son Egbert for a time and then became a nun or possibly abbess of Minster Convent which she had founded, endowing it and gathering a community of seventy-five sisters. The holy Archbishop Theodore of Canterbury may have tonsured her. The saint had desired to live a quiet life, but in 679, after the death of her sister St. Etheldreda (again from the plague), Abbess of the double Monastery of Ely, she moved to Ely and became its next abbess. Her daughter St. Ermenhildhad joined St. Sexburga as a nun at Minster and, according to one version, succeeded her as its abbess.

In 695, St. Sexburga, a well-experienced superior, organized the uncovering and translation of St. Etheldreda’s incorrupt relics (Bede, Church History, b. IV). She ruled Ely Monastery for over twenty years and reposed peacefully on July 6 at a very advanced age.

St. Sexburga’s relics were first translated by St. Ethelwold of Winchester in the tenth century. And in 1106, the solemn translation of the relics of Sts. Etheldreda, Sexburga, Withburgh and Ermenhild into new shrines at the Ely Cathedral-Monastery took place. St. Sexburga’s relics were located to the east of St. Etheldreda’s. The relics of all these saints and their shrines were destroyed during the Reformation, though some relics of St. Etheldreda and a couple of shrine fragments survive to this day. St. Sexburga is represented in sculptured scenes of St. Etheldreda’s Life at Ely Cathedral. This holy queen and abbess was esteemed for her labors and contribution to the spread of Christianity and monasticism in Kent and East Anglia. Many other royal women and queens consort of the era were inspired by her example and strove to end their lives in widowhood as nuns or founders and abbesses of monasteries. The role of this saint in the development of royal piety in early England cannot be overestimated. Her name occurs in many late Saxon litanies. In art, she is depicted as a crowned abbess with a palm branch. She appears on stained-glass windows of some parish churches and in Chester Cathedral.

Now let us say a few words about St. Sexburga’s two holy daughters.

St. Ermenhild (Eormengild, Ermenilda; feast: February 13) was born in the 640s and reposed in the early eighth century. She is mentioned in the Kentish Royal Legend (despite its confusing title, the manuscript is reliable). She married King Wulfhere of Mercia (a son of the infamous King Penda; ruled 657–675) and converted him to the faith. She became the mother of St. Werburgh of Chester (who ruled several monasteries in Mercia), the future King Coenred of Mercia (ruled 704-709), and probably the holy princes Wulfhad and Ruffin who were martyred as boys.

She made enormous efforts to change the minds and way of life of Mercians who had recently converted from paganism, trying to wipe away the vestiges of idolatry. Like her mother, St. Ermenhild won the hearts of many subjects through her example, compassion and kindness. After Wulfhere’s death in 675 she became a nun at Minster-in-Sheppey where she lived for some years with her mother and most probably succeeded her as its abbess when the latter resigned and moved to Ely. Though, like Sexburga, Ermenhild dreamed of peaceful monastic life, she later also had to move to Ely where she succeeded St. Sexburga as its abbess after her death, becoming the third royal superior of that great monastery. Alas, nothing is known about her abbacy, though St. Ermenhild’s medieval veneration was extensive. Her daughter St. Werburgh succeeded her as abbess for a short time. Her name can be found in some late Saxon litanies.

St. Ercongotha († c. 660; feast: February 21) was sent as a girl to the convent of Faremoutiers in Gaul because of the shortage of monasteries in England at that time. There she became a nun under her aunt, St. Ethelburgh, but reposed when very young. St. Bede praised her (Church History, b. III), saying that many miracles and signs were associated with this holy maiden. On the night she reposed, everyone at the monastery heard angels sing and saw an unearthly light descending from heaven. She was buried in the Church of St. Stephen the First Martyr there.

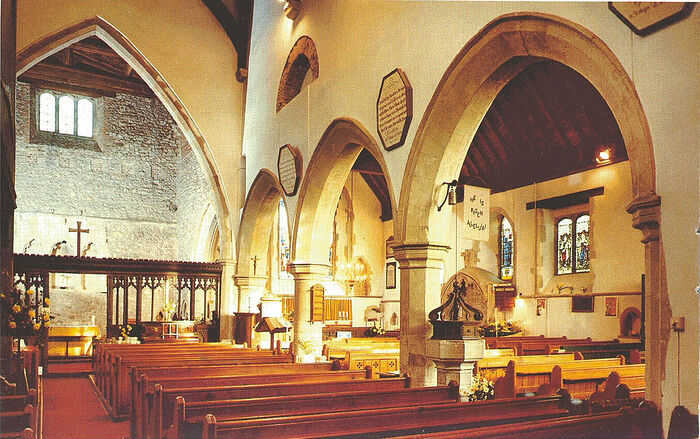

The Isle of Sheppey (its name derives from Old English and means “island of sheep”) is an island off the north coast of Kent in the Thames estuary, separated from the mainland by the Swale, a narrow channel. One of its chief towns is Minster, on the north coast with a population of 21,000, where prayer has continued for over 1300 years. In the seventh century, it was a remote yet important outpost of Christianity in England, but now it is a large parish church in the town center with a special atmosphere inside. Minster Convent was plundered by the Vikings in 855, later restored while retaining much of the original fabric, but in 1052 suffered again at the hands of Earl Godwin. After the Norman Conquest, King William I partly rebuilt the church and allowed the nuns from Newington to live here, but the community had a miserable existence. Subsequently, it was refounded as a Catholic priory for nuns in the 1120s. The convent church had an unusual layout: it consisted of two adjoining churches standing next to one another—the north Saxon one for the nuns and the later south one for the parishioners. Now the two parts are still separated by a wall with a series of arches, making up a large single building. In the Middle Ages, curtains were used to cover the arches.

Minster Abbey, Kent (kindly provided by the congregation of Minster Abbey from West Sheppey Parish)

Minster Abbey, Kent (kindly provided by the congregation of Minster Abbey from West Sheppey Parish)

The Minster Priory was dissolved under Henry VIII: soon most of the claustral buildings were demolished, but the double church was spared. Since then, the church has been used as an Anglican parish church known as “the Abbey Church of the Blessed Virgin Mary and St. Sexburgha” (the only church that bears her name), or “Minster Abbey.” The edifice is built of flint and rubble. Since the Isle of Sheppey had no stone, the materials were brought by the River Medway and the Swale from Caen in Normandy. The northeast and oldest section of the church (the chancel of the north half of the church) is also known as St. Sexburga’s Chapel. It still retains much fabric and even fragments of windows from the Saxon building, along with some Roman tiles, making this church one of the earliest surviving stone churches in England. The south section—the former town parish church (the south chancel and nave with a porch)—dates from the twelfth century and later. The main style is Early English Gothic.

Exterior of Minster Abbey, Kent (kindly provided by the congregation of Minster Abbey from West Sheppey Parish)

Exterior of Minster Abbey, Kent (kindly provided by the congregation of Minster Abbey from West Sheppey Parish)

The church once housed an unusual twelfth century sculpture of the Madonna with Child, which is now kept at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. Among the internal treasures are a fine twelfth century oak screen (which runs north to south, separating St. Sexburga’s Chapel from the northern nave), traces of a St. Nicholas medieval wall painting, St. Sexburga’s window installed for Queen Victoria’s diamond jubilee (1897), nineteenth-century stained-glass windows and many monuments of various periods. It was restored by the architect Ewan Christian (1814-1895). The tower is from the fifteenth century and incomplete due to the Reformation. The former priory gatehouse is now used as a museum. There are three wells around the church, located by the Gatehouse, under a shop in Minster High Street and in the garden of a house in the adjacent Falcon Gardens, according to Minster Abbey’s website. Finally, Minster Abbey is the prototype of the church in several chapters of Charles Dickens’ novel, The Old Curiosity Shop, based on the author’s impressions of his stay in Minster.

Inside Minster Abbey, Kent (kindly provided by the congregation of Minster Abbey from West Sheppey Parish)

Inside Minster Abbey, Kent (kindly provided by the congregation of Minster Abbey from West Sheppey Parish)

***

Among the other local saints of southern England we should also mention:

—St. Beornwald (Bernwald; the eighth or tenth c.; feast: December 21)—a righteous priest who lived in what is now the small and pretty town of Bampton in Oxfordshire and is now its patron. In two post-Norman martyrologies, he is called “confessor” and “priest and martyr.” Nothing else is known about him, but his grave may still exist in the fine eleventh-century St. Mary’s Church with some Saxon elements (formerly a minster) in Bampton, where a niche in the north transept east wall contains remnants of his shrine with a marble slab of it at the foot. His feast is celebrated there. Bampton is known as the location of the filming of Downton Abbey.

—St. Diuma (Dimma; † c. 660; feast: December 7) was an Irishman who moved to Northumbria, was consecrated bishop by St. Finan of Lindisfarne and sent by him as the first Bishop of Mercia. His companions were St. Cedd, Betti and Adda. After King Penda’s death the missionaries had more freedom and successfully evangelized the population. St. Bede noted that St. Diuma was Bishop of the Mercians and the Middle Angles and that his apostolate was short yet most fruitful. His main center was in Repton, he may have founded Peterborough Monastery and was buried in what is now the tiny town of Charlbury in Oxfordshire, where his relics may still be present in an unknown location in the ancient St. Mary’s Church.

—St. Edwold (the ninth c.; feast: August 29) is said to have been the brother of St. Edmund of East Anglia. After a vision he travelled far away to what is now Dorset and lived the rest of his life as hermit on a hill close to Cerne. His diet consisted of bread and water; he prayed much, performed many miracles and was buried in his cell. In the tenth century, his relics were translated to the famous St. Peter’s Monastery of Cerne in Dorset. He is patron-saint of the village Cerne Abbas. Some structures of the monastery of Cerne survive. This was the third richest in England, and there is the healing “Silver Well” by legend founded by St. Augustine of Canterbury nearby. The prominent author Aelfric of Eynsham taught at the monastery. The village is also worth visiting thanks to its ancient parish church and beautiful gardens.

Holy Cuthburga, Cwenburga, Dicul, Edburga and Sexburga, pray to God for us!

Acknowledgements:

I express sincere gratitude to Gordon Edgar from The Minster Church of St. Cuthburga for photographs of Wemborne Minster Church and additional information; to Rev. Paul Rush and Nestie Strauss, the administrator of the West Sheppey parish, for photographs and additional materials on the Minster Abbey Church; to Rebecca Adams for providing photographs of the church in Stratton Audley; and to Gillian Salway for a photo of the rood screen fragment at the Stanton Harcourt church.