July 17 is the feast of the holy Royal Martyrs—the family of the last Russian Emperor St. Nicholas II. While commemorating them, let us remember those who walked the path of the Cross with them and remained faithful in the days when betrayal became the norm.

Archimandrite Nicholas (Gibbes), the former English tutor of the holy Tsarevich Alexei “All around me is treason, cowardice and deceit!” Emperor St. Nicholas II wrote in his diary the night after his abdication. He had every reason to say this—betrayal of the monarch had swept like an epidemic across all levels of society. There were traitors even among the grand dukes: Dirty rumors about the Royal Family were invented and then put onto the pages of tabloid publications and into the minds of city people. Let’s recall that the Tsar’s cousin Kirill Vladimirovich led the Guards to swear allegiance to the rebellious Duma the day before the abdication. (His descendants are now trying to claim the Russian throne, to the bewilderment of both opponents and supporters of restoration of the monarchy). There were traitors among the generals as well—the chief of staff of the Headquarters of the Supreme Commander, M. Alexeyev, and the commander-in-chief of the armies of the Northern Front, N. Ruzsky, played key roles in overthrowing the throne, but these were not the only traitors in general’s epaulettes. There were traitors were among the lower rank officers as well—for example, immediately after the Tsar’s abdication, the Commander of His Majesty’s Own Railway Regiment, S. Zabel, rushed to remove the royal monograms; he was shamed by a soldier who indignantly refused to be involved in this. But there were plenty of traitors even among soldiers. Those who had sworn allegiance to the Sovereign would soon mock the imprisoned Royal Family with coarse ingenuity. “Hide your mug, or I’ll fire!” shouted one of the “heroes” of the revolution to Princess Tatiana Nikolaevna (a young beauty who worked as a surgical nurse in the infirmary throughout the war) when she looked out of the window. And there were a lot of similar traitors in a soldier’s uniform. The terrible prophecy of the poet Fyodor Tyutchev (1803–1873), from a poem written half a century before the fateful year of 1917, came true: “Treason is everywhere—the Tsar held captive! / And Rus’ will not rise to save him...”

Archimandrite Nicholas (Gibbes), the former English tutor of the holy Tsarevich Alexei “All around me is treason, cowardice and deceit!” Emperor St. Nicholas II wrote in his diary the night after his abdication. He had every reason to say this—betrayal of the monarch had swept like an epidemic across all levels of society. There were traitors even among the grand dukes: Dirty rumors about the Royal Family were invented and then put onto the pages of tabloid publications and into the minds of city people. Let’s recall that the Tsar’s cousin Kirill Vladimirovich led the Guards to swear allegiance to the rebellious Duma the day before the abdication. (His descendants are now trying to claim the Russian throne, to the bewilderment of both opponents and supporters of restoration of the monarchy). There were traitors among the generals as well—the chief of staff of the Headquarters of the Supreme Commander, M. Alexeyev, and the commander-in-chief of the armies of the Northern Front, N. Ruzsky, played key roles in overthrowing the throne, but these were not the only traitors in general’s epaulettes. There were traitors were among the lower rank officers as well—for example, immediately after the Tsar’s abdication, the Commander of His Majesty’s Own Railway Regiment, S. Zabel, rushed to remove the royal monograms; he was shamed by a soldier who indignantly refused to be involved in this. But there were plenty of traitors even among soldiers. Those who had sworn allegiance to the Sovereign would soon mock the imprisoned Royal Family with coarse ingenuity. “Hide your mug, or I’ll fire!” shouted one of the “heroes” of the revolution to Princess Tatiana Nikolaevna (a young beauty who worked as a surgical nurse in the infirmary throughout the war) when she looked out of the window. And there were a lot of similar traitors in a soldier’s uniform. The terrible prophecy of the poet Fyodor Tyutchev (1803–1873), from a poem written half a century before the fateful year of 1917, came true: “Treason is everywhere—the Tsar held captive! / And Rus’ will not rise to save him...”

But, as always happens in “fatal moments”, the betrayal of some made the loyalty, nobility and selflessness of others shine all the more brightly. And there were also people who remained faithful to the holy Royal Martyrs. Of course, they were far fewer than the traitors, which is quite natural: Those who choose the cross are always fewer than those who choose to save their necks.

The names of the faithful servants and close ones who voluntarily shared imprisonment and exile to Siberia with the Royal Family are inscribed forever on the pages of Russia’s glory. These are Dr. Eugene Botkin, the servant Aloysius Trupp, lady-in-waiting Anna Demidova, and the cook Ivan Kharitonov, assassinated together with the Royal Martyrs. Some a little earlier, others a little later than the Royal Family, but for the same crime—faithfulness to the Royal Martyrs. The maid Catharina Schneider, the Marshal of the Court Vasily Dolgorukov, Adjutant General Ilya Tatishchev and the servant Ivan Sednev were slain as well. Many other names can also be mentioned.

The destinies of these people remind us of the Savior’s words: Then shall two be in the field; the one shall be taken, and the other left. Two women shall be grinding at the mill; the one shall be taken, and the other left (Mt. 24:40-41). After the Sovereign at Headquarters and the Tsarina with the children in Tsarskoye Selo had been arrested on March 8/21, the revolutionary authorities gave all the servants a choice: to leave or to stay. They were to obey the rules of imprisonment, and no one would be allowed into the palace. The Adjutant General of the Emperor’s retinue, A. Resin, and some others with him, chose to leave. But Countess Anastasia Hendrikova thanked God for having managed to run into the palace two hours before the doors slammed. In February, she went to Kislovodsk to visit her sick sister. On the way she heard about the events in Petrograd and, without seeing her sister, rushed back to Tsarskoye Selo. “Nastenka, an angel”, as they called maid of honor Hendrikova, followed the Most August prisoners to Tobolsk. But she was not allowed to go to Ekaterinburg and was imprisoned in Perm. On September 4, Chekists came for her. She said calmly, “What? Already?”, and asked her cellmates in French to write to her sister. The countess was taken to be shot, but at the last moment the thrifty Chekist begrudged her a bullet and smashed off half of the thirty-year-old woman’s skull of with the butt of his gun. Her body was thrown into the sewers. When White Guards later found it, Hendrikova was easily identified: After seven months in the sewage, her body remained intact, even the nails retained a pinkish tint.

In March, the mother of another lady-in-waiting, Baroness Sophie von Buxhoeveden, was seriously ill. The baroness stayed with the prisoners and was not present at her mother’s funeral. Iza, as she was called by the Royal Family, could not go with them to Tobolsk—she had an appendectomy. Once she got better, she began to seek permission to join the exiles. She received permission on the last day of the Provisional Government’s existence and immediately left for Siberia. But Iza was not allowed to see the royal prisoners, which saved her life: after long ordeals, she ended up in England.

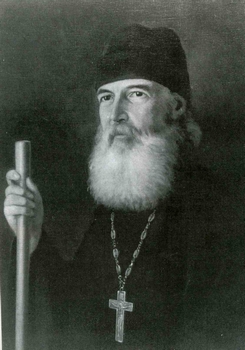

Pierre Gilliard and Charles Sydney Gibbes

Pierre Gilliard and Charles Sydney Gibbes

It is impossible in a short article to speak about all the faithful who stayed with the Royal Family to the end. However, we cannot but mention the feats of two foreigners, who, unlike the Russian subjects, were not even bound by oaths. The tutor of the Crown Prince, who also taught French to all the royal children—the Swiss Pierre Gilliard—served the Royal Family in good faith and fidelity for thirteen years. Without a moment’s hesitation, he shared their imprisonment and exile in Siberia. On March 8/21, his colleague, Charles Sydney Gibbes, who taught English to the royal children, went to the city for news at the Empress’s request. When he returned, no one was being let into the palace. The stubborn Englishman began to fight for the right to be with the arrestees and won. But the pass to the palace was issued on August 2, one day after the Royal Family had been exiled. Gibbes began a new phase of his struggle and sought permission to travel to Siberia, joining the others in Tobolsk...

Despite their protests, Gilliard and Gibbes were separated from the Royal Family in Ekaterinburg. Apparently it was providential: Because they survived, the two impartial foreigners were able to testify to the entire world the truth about the slandered Royal Martyrs. True, Gibbes did not write memoirs and even criticized Gilliard, who in 1921 published the book, Thirteen Years at the Russian Court. Gibbes believed that his own relations with the Royal Family were too personal. But sometimes, in moments of frankness, he would share his memories with those closest to him: his reminiscences contained many precious details...

In 1934, Gibbes was baptized into Orthodoxy with the name Alexei—in honor of the Tsarevich; and a year later he was tonsured a monk with the name Nicholas after the Tsar. For the rest of his life (he lived till eighty-seven) Archimandrite Nicholas carefully kept the relics associated with the Royal Martyrs. Three days before his repose, the icon once presented to him by them renewed itself above his bed in the bedroom...

When one “is taken” and the other “is left”, this does not happen by fate or predestination—people choose their own destiny. Two sailors, under-tutors of the Crown Prince, made differing choices. From the first days after the Tsar’s abdication the boatswain Andrei Derevenko was rude to the Tsarevich and in every possible way showed his “revolutionary character”; later he would also steal the Tsarevich’s things. The sailor Klimenty Nagorny stayed with the Royal Family, followed them to Siberia and was one of the first to be shot—in late May or early June. He was shot for allowing no liberties to the guards, defending the Tsarevich and the princesses. He foresaw his fate in advance and did had no regrets. It is noteworthy that one of the regicides, Medvedev (Kudrin), said of the Royal Family’s servants: “From the very beginning we suggested that they leave the Romanovs. Some left, and those who remained declared that they wanted to share the monarch’s fate. So let them share it…” The bandit couldn’t have understood what he was saying. Can a person dream of anything greater than sharing the saints’ fate?!

Sometimes people ask: “Why didn’t the Russian Orthodox Church, unlike ROCOR, canonize the faithful servants?” The reason is that some of them were heterodox: Trupp was a Catholic, and Schneider was a Lutheran... However, issues related to canonization are not the responsibility of the laity, but of the Church hierarchy; thus, let us be guided by the words from the report of Metropolitan Juvenaly of Kolomna and Krutitsy: “Today the most appropriate way to honor the Christian labors of the Royal Family’s faithful servants, who shared their tragic fate, is probably the continuation of this labor in the lives of the Royal Martyrs.”

You can read more about the lives of the faithful royal servants and closest in the books:

The Faithful: on Those Who Did not Betray the Royal Martyrs, by O. Chernova; The Life and Tragedy of Alexandra Feodorovna, Russian Empress, by Baroness von Buxhoeveden; The Real Tsaritsa by Lili Dehn; Memories of the Royal Family and Their Life Before and After the Revolution by Tatiana Melnik-Botkina, Eugene Botkin’s daughter; “Memories of the servant Alexei Volkov, who miraculously escaped execution” in the collection, The Royal Martyrs in the Memoirs of Loyal Subjects; Tsarevich Alexei in the Memoirs of His Tutors, which includes Gilliard’s reminiscences and a biographical sketch by Gibbes.