Metropolitan Athanasios of Limassol shared this story at a meeting with parishioners on September 13, 2023.

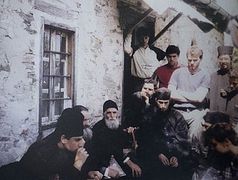

St. Paisios the Hagiorite (center), Schemamonk Joseph of Vatopedi (left) and Metropolitan Athanasios (right)

St. Paisios the Hagiorite (center), Schemamonk Joseph of Vatopedi (left) and Metropolitan Athanasios (right)

Today I have an anniversary. No, not a birthday, but a very important date in my life, connected with an event that happened almost fifty years ago. Now I am sixty-four, and it took place when I was eighteen. Then I came to study at University of Thessaloniki and got to know Holy Mount Athos. Of course, I had heard about Mt. Athos before from stories of various people, but that knowledge was very limited. So, listening to their testimonies, I got the desire to visit the Holy Mountain.

Moreover, from about the age of fifteen I corresponded with Elder Joseph,1 who then lived at New Skete, and it was my only contact with the Holy Mountain. True, I had little understanding of spiritual things at that time, but communication with Stavrovouni Monastery2 helped me a lot. Then the Monasteries of Stavrovouni and Trooditissa3 were cenobitic4 with the Athonite way of life. Stavrovouni Monastery was very strict and remains such to this day. I went to this monastery and confessed my sins to Elder Athanasios.5

The first time I went to Mt. Athos was when I became a student at University of Thessaloniki. In late September I arrived in Greece and after six or seven days went to Mt. Athos. My first visit was a disaster—I didn’t like Mt. Athos at all. I immediately wanted to leave there! It was a kind of demonic delusion. Everything was going awry. At first I missed the bus that I had wanted to take to Philotheou Monastery. Then I met Elder Joseph at the Protaton6 on a tractor, and I didn’t want to tell him that I was the Andreas Nikolaou who corresponded with him. By the way, when I was ordained, I didn’t tell him about it, and when he met me he asked, “What’s your name?” I replied, “Antonios.” He said to me, “Do you know Andreas Nikolaou?” I told him, “No, I don’t know him.” The elder responded, “Strange.”

So, in the afternoon we arrived in Koutloumousiou Monastery (Elder Joseph drove us there). Once we entered the courtyard, he started berating a monk who did not answer anything, only asking the elder for the blessing to make bows. Actually, the elder had a good reason to rail at him, because that brother was a cook, and that day he had made soup from some weeds, which then made everyone’s stomachs ache.

In the evening the elder invited me and other guys to the meeting room to talk with us. He said that he was already nearing death (he was about sixty at the time) and that he saw his coffin in front of him. I kept trying to discern where his coffin was in the room, but it was just a figure of speech.

Then we went to our cells to rest, but it seemed that all the demonic powers had come down to us. It was a terrible night. In the morning we went to church, where there were old monks who behaved freely—for example, they could talk during the service. The next morning, once it was light, I fled from Mt. Athos and said that I would never set foot there again. I didn’t like anything there at all. I got to Karyes and from there I went straight to Thessaloniki.

On my way back different people asked me where I had been, what I had seen and who I liked on Mt. Athos, but I said that I didn’t like it there at all. By Divine Providence, Ioannis Fundoulis, a teacher of the Department of Theology, sat next to me at that time and asked me, “Who did you see on Mount Athos? Elder Joseph? Oh, he’s wonderful!” But I had the worst opinion about this man and Mt. Athos in general. I returned to Thessaloniki, went to university, and there everyone was extremely enthusiastic about Mt. Athos. What could I tell them? That I arrived there, didn’t like anything and the next day I fled from there? For example, I was asked, “Have you been there?” “I have,” I replied. “Did you like it?” “Yes, I did.” But I didn’t tell them anything else and just listened to their stories.

Ten or fifteen days later I decided to go there again with my fellow students. There were about ten of us. They were more experienced because they had been there more than once. On the way we were told various things: about the elders, St. Paisios, St. Ephraim of Katounakia, Ephraim of Philotheou and Elder Joseph. I was very skeptical. We went to Katounakia Skete. We moored at Karoulia and then we had to climb the mountain for about an hour and a half, which was very hard for me as I was not used to it. On the way we heard a lot about the elder, that he was a prophet, radiated light, was very strict and so on. So, we reached Katounakia and found the elder there. It was October 6, 1976 according to the old calendar, the feast of the holy Apostle Thomas. When we entered, the elder was sitting and cutting out the seals for prosphora.

“Bless us, Geronda,” we said to him.

“God bless,” he answered us. “What do you want?”

“We are here to see you.”

“What do you want to look at me for?”

“We want to receive your blessing.”

“Okay.”

One of my companions came up to the elder and handed him two boxes of kurabiye cookies. He looked at us strictly and said:

“You’ve brought kurabiye cookies. Do you know where you’ve come?”

“To Katounakia Skete.”

“Katounakia and kurabiye cookies are incompatible.”

He opened the window and threw the kurabiye cookies out of it. The next thing we expected was that he would throw us out of the window as well. Then everyone began to come up to him one by one and kiss his hand. The elder was sitting silently. I came up last, and once I approached him, he suddenly exclaimed, “Oops, the thief is caught!” I almost died on the spot. I was already afraid of him after listening to my companions’ stories, and besides, everyone around me fixed their eyes on me at that moment. The elder looked at me with a piercing gaze, and then the thought flashed through my mind: “Oh, Most Holy Theotokos! Now he’ll reveal all my sins, bringing dishonor on me.” I was shivering and wet with sweat. He told me, “You are related to us.” I said to him, “Geronda, are you from Cyprus?” He replied, “You’re slow-witted.” I didn’t speak anymore.

Then he invited us to sit down. We obeyed. He talked with us for a while, and then said that since it was time for the evening service, we should take prayer ropes and pray for an hour, and then we would all go together to the cell to commemorate the Apostle Thomas, and there he would say goodbye to us. The elder wondered, “Do you have prayer ropes?” All the guys said yes and took them out of their pockets. When I took out mine, which was five centimeters in size, the elder told me, “Is this a child’s prayer rope?” Then he brought me his huge one. I was shocked when I saw it. “Do I need to pray with this one?” I asked. “Yes, and many times,” the elder replied. Thus, we took the prayer ropes, prayed as best we could, and then went to the cell of the Apostle Thomas. On the way the elder held my hand for support, but I constantly slipped on rocks, and he supported me, and then he said, “Listen, who should lean on who?” “Oh, Geronda, I’m sorry, I’m not used to these paths,” I told him. We dropped in at the cell, then at Dionysiou Monastery, then the Burazeri Cell, and next proceeded to Elder Paisios.

At that time life on Mt. Athos was very simple, I would even say primitive—there were no roads, no telephones, no electricity, nothing. We came to Elder Paisios. We had already heard a lot about his holiness. There were three of us: me and two of my fellow students, one of whom was a deacon. We rang the bell. The elder did not come out to us. The deacon said, “Let’s pray that the Lord will enlighten the elder and he will open the door.” The elder lived in such a wilderness, it was difficult of access. We took out our prayer ropes, prayed, and on the last prayer knot we heard his voice. We saw his silhouette from afar: he was about fifty or fifty-five at that time. He did not look like an elderly man, but he was very thin, with some green blanket on his shoulders, because he felt very cold. Elder Paisios came out to us and invited us into his cell.

He told us various things, but he didn’t make any impression on me. I thought he was crazy, and since he was crazy, people believed he was a saint. For example, we told him one thing, but he answered us another. Moreover, he told us various jokes, and the guys laughed. I didn’t find what he was telling us funny. When it was time to leave, I was completely disappointed in Elder Paisios. Then we asked for his advice on what we should do. He replied that since we were young, we should make many prostrations. We wondered, “How many prostrations?” And he replied, “Many, many.” Then he patted us on the back and asked us to go. Once the elder said goodbye to us, the whole space was filled with an unusually strong fragrance. We didn’t know what to do or how to react to that. We wanted to go up to him and ask him what it was, but he saw us out of his cell, saying, “Well, go, go!” Then he closed the door and left, and we ran to the Burazeri Cell.

It was the first time I had seen Elder Paisios. Later I realized that this man was a saint, having visited him many more times between 1976 and September 1977. On September 13, 1977, I went to see him in the cell in the morning. The elder met me and said, “Greetings, deacon! I just need a deacon today; we’ll have a big feast in the evening—a bishop will come with singers, with people, and we’ll cook...” I believed him that he would arrange a feast. He said to me, “You’ll stay with me today.” I jumped with joy, because I often visited him throughout the year; many dreamed of staying with the elder for a while, but he did not allow anyone.

I spent the whole morning with him. We did some work in his little church, and in the afternoon he called me to eat. I asked him, “Where are we going to eat?” He had neither a kitchen nor a table. He took some oilcloth and spread it on a stone in the yard. Then he took out some breadcrumbs, probably from the time of Fr. Tikhon,7 brought a couple of onions from the garden, and then remembered that someone had given him a can of squid. However, he had no idea how to open it, because he didn’t have an opener. Then he took an adze, rapped for a while and somehow opened it. He gave me canned squid, and we sat down and had a bite in this “desert”.

In the evening we celebrated Vespers with prayer ropes, and then the elder sent me to rest, because he was going to serve the Vigil at night. Of course, nobody came: neither a bishop, nor priests, nor singers—there were just two of us. In the evening, around 6 o’clock, when it was getting dark, he said to me, “We will serve the Vigil with prayer ropes, and at midnight I will call you to read the prayers before Holy Communion, and in the morning a priest from Stavronikita Monastery will come to celebrate the Liturgy. If you suddenly hear a noise at night, don’t be afraid—these are jackals.” The elder lived in the desert, and, naturally, wild animals would roam around it. No one else lived within sight of his cell. There were two rooms in the elder’s house: Elder Paisios lived in one, and I stayed in the other. I asked him how we would celebrate the Vigil. He said to me, “Listen to what should be done”, and gave me the plan so that I could follow it and not fall asleep. This is what he told me to do: 300 prayers—that is, a prayer rope of 300 knots: “Lord Jesus Christ, have mercy on me”; 300 more prayers with another prayer rope: “O Most Holy Theotokos, save me”; another prayer rope: “Lord Jesus Christ, have mercy on Thy world”; another one: “O Most Holy Theotokos, save and help Thy world”; another one for the departed; one for the living; one to the Cross: “O Cross of Christ, save us by thy power”; and another one for glorification: “Glory to Thee, our Lord, glory to Thee”. The elder told me that when I finished it, I must start again.

We began the service at about six or seven in the evening. I could hear his movements through the wall. Since the holy Elder Paisios had had tuberculosis and three-quarters of his lungs had been cut out, leaving only half of one lung, he got tired easily and would start gasping for air. Since the walls were very thin, I could hear him breathe. Every hour and a half he would knock on the wall and ask me, “Are you asleep, deacon?” I would reply, “No, Geronda, I’m awake.” Time flew by so quickly that I didn’t even notice it. The elder’s prayers were very strong, and I felt the grace that was coming from him.

At six in the evening Byzantine time (00.30 secular time) he invited me into the church to read the prayers before Holy Communion. I went to church with him. The church was very small: the iconostasis consisted of only five icons and was 1.5 meters from me. Once Fr. Tikhon himself, a holy Russian elder, Elder Paisios’ spiritual father, used to serve in this church. So, the elder stood me in the stasidia, gave me a candle and told me to read, and he stood next to me and uttered the glorification from the prayers before Communion: “Glory to Thee, our Lord, glory to Thee”, and I read everything else. After each verse the elder made a bow, and I stood in my place and read. When we got to the prayer: “O Most Holy Theotokos, save us. Mary, Mother of God...”, we heard a noise like the wind, although there was no wind, because the windows and the doors were closed, and the church was filled with light in an instant, and an icon lamp near the icon of the Most Holy Theotokos started swinging. I was confused: I looked at the elder, but he made a sign that I should not speak and knelt down. I remained standing with a candle in my hand. I noticed that the church was filled with light, because in order to read I no longer needed my candle. It lasted about half an hour or forty minutes. All this time the elder was on his knees, and I decided to continue reading everything myself. Once I got to the prayer of St. Simeon the New Theologian: “From lips tainted and defiled, from a heart unclean and loathsome”, everything went dark in the church, the icon lamp stopped swinging, and everything returned to normal. The elder remained on his knees, saying nothing. When we finished the prayers before Communion, he called me to sit for a while. We sat down, and I asked him:

“Geronda, what happened?”

“What do you mean?”

“When we were in church.”

“What did you see?”

I told him about the light and the icon lamp.

“Did you see anything else?” the elder asked me.

“No, nothing else,” I answered.

“There was nothing there.”

“Why nothing? I saw it! There were five icon lamps in the church and only one was swinging, which means that it was not just because of a draft.”

The elder suddenly said to me:

“Yes. Haven’t you read that the Mother of God walks around cells in the evening and looks at what monks are doing there? She came to us, saw two crazy people and shook Her icon lamp a little to greet us.”