Source: Daily Press

November 28, 2015

Not long after stepping into the Chrysler Museum of Art's new exhibit of Byzantine and Russian icons, you may wonder if the dimly lit galleries have undergone some sort of elusive but perceptible transformation.

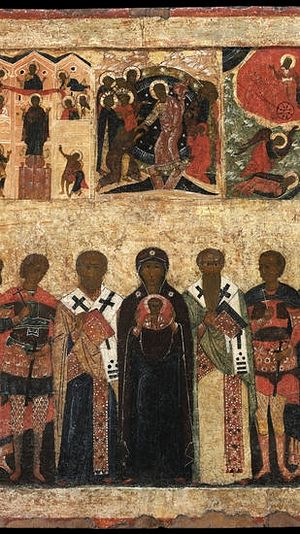

Though more than 150 rare works of art from the 10th through 19th centuries fill the cases and walls, the experience here is not like those encountered in most galleries or museums.

Instead, face after face depicting Christ, the Mother of God, the Apostles, the Saints and even a few warrior angels combine to make this space feel like a very old, mysterious and spiritually charged temple.

That supernatural change of venue has been the mission of Orthodox Christian icons for 1,500 years, during which they were created primarily not as aesthetic objects but as gateways to an otherworldly realm.

To the devout, they provide an immediate link to a divine presence — and gazing at one is like seeing a path unfold between the mundane and heaven.

"These icons are powerful in a religious and personal sense because they can be revelatory to the person viewing them. They're powerful in a historical sense because some were used by believers to turn back enemy armies and cure the sick. They're powerful as works of art," said Chrysler Manager of Interpretation Seth Feman.

"For the faithful, that power is a fact. It's unquestionable — and their reaction is to venerate."

Landmark works

"Saints and Dragons: Icons from Byzantium to Russia" comes from the Museum of Russian Icons in Massachusetts, where Director and Chief Curator Kent Russell wanted to put together an exhibit exploring the history of the form from its emergence in Constantinople during the 500s to its adoption and continued development in Russia beginning about 1,000 AD.

Nearly a decade before Russell starting selecting examples from his own formidable collection, however, Prince Charles of Great Britain — a long-time admirer of icons — asked the British Museum to make its renowned holdings more accessible to the public.

That royal request opened the famed institution's vaults, enabling Russell — who worked closely with its curators — to put together an unprecedented survey that combines nearly three dozen masterworks from London with the finest examples from the Museum of Russian Icons, which boasts the largest and richest collection of Russian icons outside Russia.

Among the treasures on loan from the British Museum are a circa 1300 Byzantine depiction of St. John the Baptist — also known among Orthodox Christians as St. John the Forerunner — and an early 1400s Russian icon known as "The Black St. George."

Trailing only slightly behind in importance are such works as a 1400s Byzantine portrait of St. Nicholas.

"The 'St. John' is among the finest examples from Byzantium to survive anywhere — and the 'Black St. George' is enormously important — one of the finest Russian icons on that subject," Russell said.

"They've never been exhibited outside the British Museum before — and I'm still astounded they agreed to lend them."

Those loans upped the ante back in Massachusetts, where Russell knew only his very best works could hope to share the stage with such masterworks.

"Even the Metropolitan Museum of Art has only maybe 20 icons," Russell says, "so part of the reason this show is so important to us is that we're trying to convey the history of an art tradition that's rarely seen and not widely understood in the United States.

"We denuded our walls to bring our best icons to the Chrysler. We wanted to look good."

Identity code

Organized as an art historical primer, "Saints and Dragons" addresses the most obvious questions first, explaining what icons are and how they are used by the faithful.

But even before visitors enter the first gallery, they pass through a corridor emblazoned with a wall-size color photograph documenting the floor-to-ceiling expanse of icons at the Cathedral of the Dormition at the Kremlin in Moscow — one of the Orthodox world's most famous and resplendent churches.

"We wanted people to see what a space like this looks like when it's completely adorned with icons," Feman says.

"Stepping into a church like this is a transporting experience. It's meant to take you someplace else."

Unlike Western art, however — which began embracing the canons of realism and originality some 600 years ago — the icons on view here draw much of their power from similarity and convention.

They're deliberately stylized and flat, Russell says, because they're meant to depict the unchanging and uniform light of the divine world rather than the shifting light of nature.

They also repeat standard poses, emblematic details and narratives, providing the faithful with a telltale code that explains and then reinforces each icon's identity and importance.

"People today look for originality in art — and these are totally the opposite. They're deliberately alike," Feman said.

"If you disguise yourself, you lose your power," Russell adds. "And that's because — in order to serve its purpose — an icon has to be recognized."

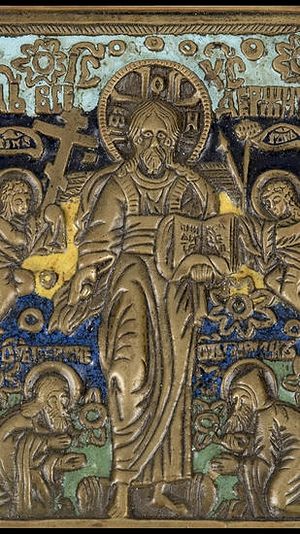

Those conventions help explain why so many portraits of St. George's fabled attack on the dragon feature a disarmingly thin spear.

If you look closely, however, the seemingly spindly weapon moves into the saint's hands — then into the body of its quarry — along a straight line whose origin is the heavens.

"The artists wanted to show the importance of that divine energy," Feman said.

"And these spears certainly don't look strong enough to vanquish anything without some divine source of power."

Many mothers

Also bewildering to modern eyes is the profusion of Marys found in Byzantine and Russian icons, where more than 450 codified ways to depict the Mother of God have emerged since — according to tradition — St. Luke painted the first image from life.

More than a dozen of the most important variants can be found here, including the Mother of God Hodigitria — in which the Virgin points the way to salvation by using one hand to gesture to her son and the other to hold him up to the viewer.

So revered did one early version become for repelling invaders in the city of Smolensk, Russia, that — in 1456 — it was copied and installed in a Kremlin cathedral.

Soon the Mother of God Smolenskaya was recognized as a new variant, Feman says, and its popularity only grew after the faithful credited it with blunting Napoleon's 1812 attack on Moscow.

Other versions include the Mother of God of the Sign, which can be recognized by the Virgin's outspread arms — which she raises in a gesture of prayer and receiving — and the youthful Christ that appears within the womb-like circle on her chest.

In the Mother of God Umilinya or Tenderness icon, Mary lovingly presses her cheek to that of her son.

"To the faithful, they all had a different purpose. They all had a different function," Russell says.

"And that determined which one you would turn to in prayer."

Erickson can be reached at 757-247-4783.

"Saints and Dragons: Icons from Byzantium to Russia"

Where: Chrysler Museum of Art, One Memorial Place, Norfolk, VA, 23510

When: Through Jan. 10

Cost: Free

Information: 757-664-6200; chrysler.org