St. Vukasin remained in Sarajevo till about June (possibly July) 1941, when many other famous residents had already begun to leave the city. Some went to Serbia where there was no genocide, others fled to the “forests”. St. Vukasin took refuge in the “forests” in Herzegovina (but, of course, not with the guerrillas—they weren’t there yet).

From that time on the saint’s family lost contact with him and did not know anything about him. The first news about his martyrdom, about the greatness of his witness to Christ didn’t reach Sarajevo until after the war. The source was Dr. Nedo Zec. He brought the news to the surviving members of the Mandrap family (Bogdan and Slavka) when he came to them for the Krsna Slava celebration in 1946.

Thanks to that meeting, news about the saint appeared around 1946, and not only in Sarajevo, but also in Mostar and Capljina. The whole Mandrap family was regarded as martyrs, and, knowing about the brutal crimes of the NDH against Serbs and Jews, the Tito police in Sarajevo did not dare touch the Mandrap house. But they preferred not to speak about St. Vukasin out loud, as well as about Jasenovac—the unhealed wound of thousands of Sarajevo families (and thousands of families throughout Bosnia and Herzegovina).

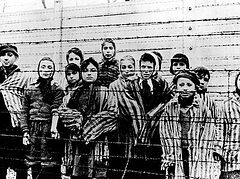

Immediately after the war, the survivors of Jasenovac met in Sarajevo. These were former Jasenovac “artisans” who had been kept in a separate section of the concentration camp and done handicraft work for the nearest Ustase garrison or ex-prisoners who had been “lucky enough” that the Germans had taken them from the Ustase, and they stayed at Jasenovac for only a short time on their way to Germany.

The aim of the survivors was to write down their shared memories of Jasenovac in order to confirm the facts of torture as far as possible.

The “camp” view of Serbian history

We, former Jasenovac prisoners, realized back during the 1940s war that for our enemies we were all “camp inmates”, a “camp nation”. Our military “allies” would show us both in 1944 and in 1989–1999 that for them we were a nation whose history was characterized by the “camp”, and not by liberation uprisings and military victories. Therefore, for Serbian history, along with the guerrilla, military and liberation experience, we should study and commit to writing our camp experience, so that it can become part of our faith, our soul, and a sign of the resilience of our nation!

The holy Elder Vukasin of Klepci is the concentration camp consciousness of Serbian history, our living faith, our witness and intercessor before Christ our Lord. With him we will always remember that it is humility and the steadfast faith of St. Vukasin of Jasenovac rather than political decisions that can lift us from the abyss.

The village of Klepci was destroyed by Croats in 1992, along with the Church of the Transfiguration of the Lord located there.

Photo: wikimedia.org Metropolitan Petar of Dabar-Bosnia (secular name: Jovan Zimonjic) was born on June 24, 1866 in the town of Grahovo to the family of the renowned priest and nobleman (vojvoda) Bogdan Zimonjic—a hero of the famous Herzegovina Uprising of 1875. In 1887 the future metropolitan graduated from the Theological Seminary of Reljevo, and then in 1893 continued his education at the Theological Department of the Chernovtsy University. After his graduation he went to Vienna, where he enrolled in the postgraduate program of the University of Vienna. In 1895, returning to Reljevo, he became a teacher at the Theological Seminary. He was tonsured and ordained priest in 1895 by Metropolitan Seraphim (Perovic), who had already suffered much during the persecution of Orthodoxy and the Serbs. His ordination took place at the long-suffering Zitomislic Monastery: it had been repeatedly destroyed and desecrated in many wars. Thus, at the very beginning of his monastic path the future metropolitan received a special blessing for martyrdom.

Photo: wikimedia.org Metropolitan Petar of Dabar-Bosnia (secular name: Jovan Zimonjic) was born on June 24, 1866 in the town of Grahovo to the family of the renowned priest and nobleman (vojvoda) Bogdan Zimonjic—a hero of the famous Herzegovina Uprising of 1875. In 1887 the future metropolitan graduated from the Theological Seminary of Reljevo, and then in 1893 continued his education at the Theological Department of the Chernovtsy University. After his graduation he went to Vienna, where he enrolled in the postgraduate program of the University of Vienna. In 1895, returning to Reljevo, he became a teacher at the Theological Seminary. He was tonsured and ordained priest in 1895 by Metropolitan Seraphim (Perovic), who had already suffered much during the persecution of Orthodoxy and the Serbs. His ordination took place at the long-suffering Zitomislic Monastery: it had been repeatedly destroyed and desecrated in many wars. Thus, at the very beginning of his monastic path the future metropolitan received a special blessing for martyrdom.

In 1901 until the end of the academic year he was a professor at the Theological Academy and an adviser at the consistory in Sarajevo (the capital of Bosnia and Herzegovina). In 1903 the Holy Synod of the Patriarchate of Constantinople, then headed by Patriarch Joachim, elected him Metropolitan of Zahumlje and Herzegovina. Vladyka was elevated to the rank of metropolitan on May 27 of the same year at the cathedral in the city of Mostar (later the Ustase turned it into a pile of ruins). Seventeen years later, on November 7, 1920, he was elected Metropolitan of Dabar-Bosnia.

Serving in the See of Zahumlje and Herzegovina, Metropolitan Petar brought the spirit of peace to the land of Herzegovina, consoling and reconciling the people. Being a great patriot, the archpastor courageously defended the Church independence of Serbia from Austria-Hungary, gaining great authority and the support among the people. His stay on Bosnian soil strengthened faith and religious activity, which later, in 1905, would bear fruit: the Serbian people received Church autonomy. Metropolitan Petar was a hierarch of the Serbian Church at a time when the Roman Catholic Church, backed by Austria-Hungary, intensified its proselytizing intrigues in these areas. The metropolitan took an irreconcilable position in relation to the occupation and seizure of historic Serbian lands by Austria-Hungary. He supported people spiritually, inspiring the faithful with the hope for a better future and spiritual liberation. His ministry and courage set an example and gave support to the Serbian nation during the annexation of Bosnia in 1908 and the First World War in 1914.

The saint received high Church awards: the Order of St. Sava of the First Degree, the Order of the White Eagle of the Fourth Degree and the Order of the Star of Karageorge.

When the Second World War broke out, he served in the capital of Bosnia, Sarajevo, in the rank of Metropolitan of Dabar-Bosnia. In connection with the bombing of the city, Metropolitan Petar temporarily took refuge at the Monastery of the Holy Trinity near the town of Pljevlja. There one day he celebrated the Sunday Liturgy with Archimandrite Seraphim, with whom he would later drink the cup of martyrdom.

On the third day of Bright Week of 1941 the metropolitan returned to Sarajevo. Meanwhile, the persecution and killings of Serbs had begun in Sarajevo and other cities of Bosnia. Many people tried to persuade the saint to leave his see for a while and move to Serbia or Montenegro. He declined all those proposals with the words: “I am a pastor, and my duty is to share both good and bad with my flock; we have one cross and one destiny, and I will share it with my people.”

On April 27, 1941, a German patrol of six officers and soldiers broke into the metropolitan’s office. One of the Nazis asked the martyr, “Are you the metropolitan who called for war against Germany? You deserve to die.” The metropolitan replied: “You are sorely mistaken, sir. There is no fault of ours in this war. We didn’t attack anyone. but don’t fool yourselves; we won’t surrender to your bullets. We won’t allow anyone to swallow us up like a drop of water. We are a nation and we have the right to life!”

Early in May of the same year, the metropolitan received a phone call from the Catholic priest Bozidar Brale, who was appointed representative of the Ustase in Bosnia and Herzegovina. He ordered Vladyka to forbid all the clergy of the diocese from using the Cyrillic alphabet and replace all inscriptions on seals with Latin ones, on the same day. He threatened that if the order was not carried out within the specified period, the metropolitan would have to answer for it. Vladyka replied, “The Cyrillic alphabet cannot be destroyed in twenty-four hours, and don’t forget, the war is not over yet!” The metropolitan’s stance resulted in his arrest on May 12, 1941.

Before Metropolitan Petar was arrested, he had managed to gather the clergy under his authority to give them instructions on further work. Some of them asked him to bless them to take refuge temporarily in Serbia, but the metropolitan replied: “Stay with your parishioners and share everything with them, no matter what may happen.”

All of them heeded his instruction. Many of those priests became martyrs, some survived the war and testified about Metropolitan Petar and everything that had happened in those terrible days.

By the evening of May 12, some Ustase agents had come to the metropolitan’s office and said that Metropolitan Petar must immediately follow them to the “directorate” for an inquiry. He spent three days in the “directorate”. On the evening of May 17 he was transported to Zagreb (the capital of Croatia) and put into a police prison. There also were Archpriest Milan Bojic; Dusan Jeftanovic, Ph.D in Theology; and Voja Besarevic, Ph.D in Theology, together with him. Photographs and fingerprints were taken. In the Ustase card file the metropolitan was given the number 29781. From there a few days later he was sent to the Kerestinec concentration camp near Samobor. There his beard was shaved off, his mantle was torn off and he was subjected to terrible tortures, after which he was transferred to another concentration camp, presumably to Gospic or Jasenovac.

There are several versions of the circumstances of Metropolitan Petar’s death, but the main thing we know is that he remained faithful to God to the end. It is unknown whether his remains were thrown into the Karpova Jama pit on Mt. Velebit or into the burning hot furnace of the Jasenovac concentration camp crematorium. But what is known for certain is that he commended his soul to the Lord, as did many believers who suffered with him for the Orthodox faith, which became for them a Heavenly ladder to the arms of Christ our Lord, to Whom belong all honor, glory, and gracious gifts—the holy martyrs and new martyrs.

From a chapter of the book, Glory and Pain of Serbia, Montenegro Metropolia of the Serbian Orthodox Church