An Orthodox icon of St. Aldhelm of Sherborne St. Aldhelm (also Ealdhelm: meaning “old helmet”) was born in 639 or 640 in the Kingdom of Wessex (which comprised what is now Hampshire, Wiltshire, parts of Dorset, Somerset, Gloucestershire, Oxfordshire, Buckinghamshire, Berkshire and Surrey) and was related to the kings of Wessex. St. Bede of Jarrow mentions him in his History of the English Church and People where he praises his holiness and talents. In the ninth century the holy King Alfred the Great admired St. Aldhelm and wrote down his story. In the late eleventh century Faritius (+1117), Abbot of Abingdon, composed his version of the Life of St. Aldhelm, and in about 1125 the prominent historian William of Malmesbury (+1143) devoted one of five volumes of his Gesta Pontificum Anglorum (Deeds of the English Bishops) to this saint. In the nineteenth century the historian John Allen Giles (1808-1884) translated most of Aldhelm’s Latin writings into English, and his work was continued by other scholars up to our times, notably by Michael Lapidge from Cambridge. A number of modern researchers have written about Aldhelm. In addition, we know about Aldhelm from his correspondence with other Church figures both in England and on the continent and from numerous traditions in south-west England.

An Orthodox icon of St. Aldhelm of Sherborne St. Aldhelm (also Ealdhelm: meaning “old helmet”) was born in 639 or 640 in the Kingdom of Wessex (which comprised what is now Hampshire, Wiltshire, parts of Dorset, Somerset, Gloucestershire, Oxfordshire, Buckinghamshire, Berkshire and Surrey) and was related to the kings of Wessex. St. Bede of Jarrow mentions him in his History of the English Church and People where he praises his holiness and talents. In the ninth century the holy King Alfred the Great admired St. Aldhelm and wrote down his story. In the late eleventh century Faritius (+1117), Abbot of Abingdon, composed his version of the Life of St. Aldhelm, and in about 1125 the prominent historian William of Malmesbury (+1143) devoted one of five volumes of his Gesta Pontificum Anglorum (Deeds of the English Bishops) to this saint. In the nineteenth century the historian John Allen Giles (1808-1884) translated most of Aldhelm’s Latin writings into English, and his work was continued by other scholars up to our times, notably by Michael Lapidge from Cambridge. A number of modern researchers have written about Aldhelm. In addition, we know about Aldhelm from his correspondence with other Church figures both in England and on the continent and from numerous traditions in south-west England.

The Kingdom of the West Saxons had been converted by St. Birinus, Bishop of Dorchester-on-Thames, between 635 and 650. Aldhelm belonged to the second generation of Christians of that large region. At the age of fifteen Aldhelm became a disciple of the Irish ascetic and hermit St. Maeldub (also Maildulf; feast: May 17/30), who during his pilgrimage in the 630s to England had stayed on. Maeldub led a holy life amid the sparsely populated Selwood Forest in Wiltshire and in time founded a school and gathered a group of disciples. St. Aldhelm joined him and received spiritual instruction and education there. The saint, like his mentor, prayed in a tiny cell day and night and worshipped in a chapel nearby. In about 661 Aldhelm was tonsured a monk. The place where St. Maeldub lived was named Mailduberi, and later Maldubesburg after his death, meaning “town of Maeldub”, and now it is called Malmesbury.

In 671 Aldhelm left Malmesbury and went to Canterbury, where its new archbishop, St. Theodore, and his assistant, Abbot Hadrian, had opened a famous seminary. So St. Aldhelm was taught there by these learned men (among the students in Canterbury at that time was St. John, Wonderworker of Beverley). Aldhelm learned the Holy Scriptures, Latin, Greek, Hebrew, the Lives of the Saints, monastic services, grammar, literature, arithmetic, astronomy, geometry, music, law, rhetoric and other sciences. St. Aldhelm was one of the ablest students in the school, where he devoted all his time and energy to absorbing knowledge and wisdom.

A very talented man by nature, under the influence of other fathers among his contemporaries, Aldhelm became a prominent scholar, writer, poet, musician, singer, pastor, archpastor, teacher and builder of churches. Many historians have regarded Aldhelm as the greatest scholar in medieval Western Europe before Bede. Besides this, the saint always combined education with prayer and a strict ascetic life; that is why the Lord bestowed on him the ability to work miracles. The saint was very tall, cheerful, friendly and good-natured by character; though a learned man, he used to speak simply with illiterate people, which is why all came to love him in the following years.

In 671 St. Aldhelm was ordained hierodeacon and after two years’ study at Canterbury returned to his beloved Malmesbury to assist his spiritual father Maeldub, who was getting weaker in his advanced age. In 673 or 674 Aldhelm was ordained hieromonk and soon after that St. Maeldub reposed in the Lord and was venerated as a saint thereafter. From 675 on St. Aldhelm served as Abbot of Malmesbury, a post that he retained for the rest of his life. He reorganized Malmesbury as a monastery, taught there, became an extremely active and energetic abbot and over the ensuing years built, according to various sources, up to four magnificent churches in Malmesbury, which he adorned. These churches were dedicated to the Savior, the Apostles Peter and Paul, the Mother of God, and Archangel Michael. He became the teacher and pastor of the Malmesbury brethren and students and gradually extended the area of his ministry, so his mission spread to most of Wiltshire, Somerset and Dorset.

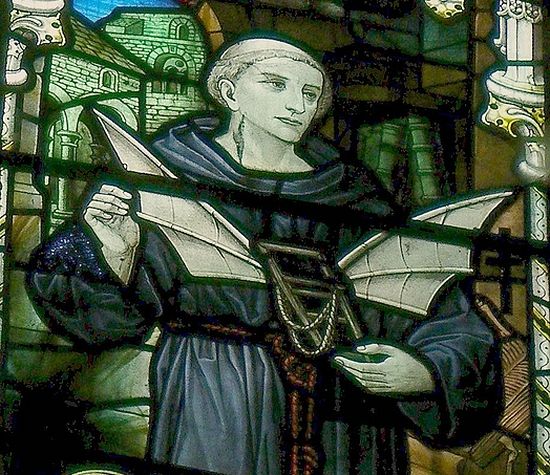

St. Aldhelm's stained glass image from the east window of Sherborne Abbey's Lady Chapel, Dorset (kindly provided by the Sherborne Abbey) But despite his busy life, the holy abbot cared for prayer most of all. He prayed unceasingly, lived a modest, austere life, kept all the fasts, and (following the Celtic tradition of the Irishman Maeldub) would stand in the waters of the stream near the abbey up to his neck for the whole night, where he would recite the whole Psalter. He did this even in the autumn and winter, when the water was icy-cold.

St. Aldhelm's stained glass image from the east window of Sherborne Abbey's Lady Chapel, Dorset (kindly provided by the Sherborne Abbey) But despite his busy life, the holy abbot cared for prayer most of all. He prayed unceasingly, lived a modest, austere life, kept all the fasts, and (following the Celtic tradition of the Irishman Maeldub) would stand in the waters of the stream near the abbey up to his neck for the whole night, where he would recite the whole Psalter. He did this even in the autumn and winter, when the water was icy-cold.

The saint took care of the ordinary people of Malmesbury and neighboring settlements, many of whom were uneducated. A very talented man, Aldhelm composed numerous songs, poems and hymns in his native Old English, and he mastered the Anglo-Saxon harp as well as other instruments (some state that he could play all the instruments available for that period). From time to time he would go to public places and sing secular songs in the vernacular. Crowds would gather around him and he would start singing spiritual songs in order to attract as many unchurched people to Christ as possible. Most often on Sundays after the church service he would often walk amid people or stand on the bridge in Malmesbury, playing the harp and performing his own hymns and songs in the manner of minstrels, and people would gather around him and listen, glorifying God.

At some point the saint noticed that some people began to skip church services, were inattentive, gossiped or left before the sermon. Then he began to sing psalms in Old English (that he had translated himself), standing on the bridge over the Avon, thus reproaching his flock, and the people came to their senses and never skipped sermons thenceforth. Later Alfred the Great collected the songs and verses of Aldhelm, and many of these songs were performed by Malmesbury townsfolk until the twelfth century. But, unfortunately, all the Old English works of Aldhelm are lost. The Holy King Alfred, who revered Aldhelm, wrote that if the saint had been strict to those under his spiritual guidance, he would not have been successful; rather, the saint preferred to display love and kindness (sometimes in a “clownish” manner), thus winning many souls for Christ.

Malmesbury prospered greatly under Aldhelm and in the Middle Ages it was considered one of the greatest monasteries in Western Europe, containing the second largest monastic library. Malmesbury also established daughter communities. From the writings and letters of Aldhelm we can see that he especially venerated the Mother of God, the holy apostles, the early martyrs and Church Fathers, attached particular importance to celebrating the Liturgy, prayers for the departed and monastic life in general. He observed nature and felt it very keenly, a fact that is reflected in many of his works.

The royalty and aristocrats of Wessex also loved and venerated St. Aldhelm. The saint gave advice to and influenced several Wessex kings and their relatives, and Malmesbury and other of his monasteries received lands and generous donations from the royal family. No doubt he influenced King Cadwalla (Ceadwalla) of Wessex, who ruled from 685 till 688. Once a ruthless and cunning pagan, he became a sincere Christian at the end of his life. He travelled to Rome to receive baptism in 689, where the sacrament was performed by Pope Sergius. Cadwalla died when in his white baptismal robe and was locally venerated after his death as a saint (feast: April 20/May 3).

St. Aldhelm was the adviser of King Ina (Ine) of Wessex who ruled from 688 till 726. This pious king took part in the restoration of Glastonbury Monastery in Somerset (under the direction of Aldhelm) and the foundation of another celebrated monastery at Abingdon in Oxfordshire. A year before his repose, Ina abdicated and together with his wife Ethelburgh went to Rome as a simple pilgrim, where he became a monk and passed away in 727 (he and his queen are locally venerated as saints on September 8/21).

The pastoral zeal of Aldhelm stretched even to faraway Northumbria in the north. Before becoming King of Northumbria, Aldfrith (ruled 685-704/5) had lived in exile in Malmesbury where he was baptized and Aldhelm became his godfather. Under Aldhelm’s influence the royal court of Northumbria of that time was famous for its high level of Christian culture and arts.

Apart from Malmesbury, St. Aldhelm founded other monasteries, namely in Frome in Somerset and in Bradford-on-Avon in Wiltshire, along with numerous churches and chapels—for example, at Bruton and Broadway in Somerset; at Bishopstrow in Wiltshire; Wareham, Corfe (at a royal palace), Sherborne and Langton Matravers in Dorset; and possibly Somerford Keynes in Gloucestershire. Traditions related to the history of the foundations of these churches abound. Once, feeling that a monastery should be founded in the thick of Selwood Forest, St. Aldhelm left Malmesbury, walked a distance and sat down in the forest, playing his lute and meditating on how he could build the new monastery. That area was notorious for the numerous robbers that lived in the forest. The thieves were captivated by the beautiful music and went out to listen and to see who was playing. Aldhelm stopped singing and addressed the men, talking to them so inspiringly and eloquently that he converted them to Christianity.

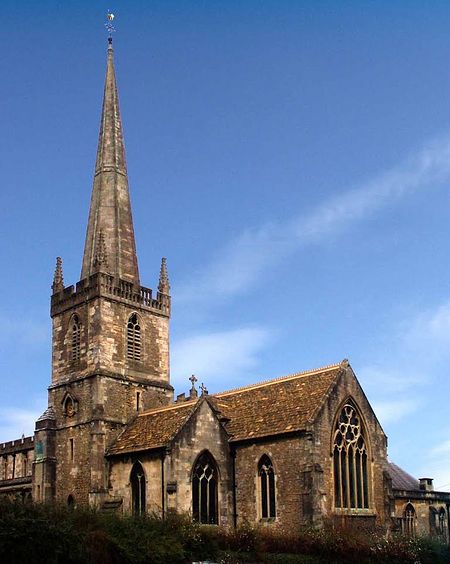

Church of St. John the Baptist in Frome, Somerset (source - Mapio.net)

Church of St. John the Baptist in Frome, Somerset (source - Mapio.net)

The band of former robbers then volunteered to help the saint build a church in the forest and the saint had it dedicated to St. John of Baptist. A monastery grew on that site; no doubt, some of the former robbers became Aldhelm’s disciples and ended their days at the monastery. Gradually the whole town of Frome developed around the monastery. Both the town and the former monastery church still survive. There are two folk traditions related to the foundation of the village and church at Bishopstrow—both of them are depicted on stained glass in the current church in this village. The first story says that Aldhelm preached on this site for so long that his ash staff which he had struck on the ground took root and grew into an ash-tree. He left it there and the place became known as “Bishop’s Tree”. The other story says that the King of Wessex offered his own staff to the saint and promised him land for a church as far as he could throw it—Hence “Bishop’s Throw”. The village is first recorded in 1086 as “Biscopestreu”, From 1270 it was known as “Bishopstrowe”—“trow “ meaning either “tree” or “cross”, so, the first story appears to be more likely.

The saint of God cared about the education of the poor and illiterate in many regions of Wessex, so he founded and encouraged others to found new schools there. St. Aldhelm wrote books, letters, treatises, sacred poems, grammatical works, and even riddles in Latin which survive to this day. They were read all over Western Europe, were popular and influenced several noted saints (for example, Boniface of Germany) till the eleventh century. His style of writing was elaborate and involved, for undereducated people even obscure. It was called hermeneutic. Most of his surviving works have been translated into modern English. Perhaps his best known work is the treatise De Laude Virginitatis (In Praise of Virginity), which he composed both in prose and verse for the abbess and nuns of Barking Monastery near London, one of whose nuns, St. Cuthburga, was his relative (she later founded a great double monastery in Wimborne, Dorset). In it he extolls the life of virginity, devout living, citing examples of numerous Biblical and early Christian saints of both sexes and referencing a host of the Holy Fathers of both the East and the West. (A Saxon drawing of him survives, showing him presenting his treatises to St. Hildelith, abbess of Barking).

His Epistola ad Acircium, a letter addressed to King Aldfrith of Northumbria, of whom we spoke above, is worth mentioning too. It comprises three treatises, namely on the number seven, on meters and metric feet. Other examples of his correspondence are those with the learned Abbot Cellanus of the Irish Monastery of Peronne (now in France); with the scholar Eahfrid who visited Ireland; Bishop Leuthere; St. Hadrian, Pope Sergius; the saint’s disciples Wihtfrith and Ethelwald; numerous abbesses and princes. There is also a poem describing his travels across western England and, notably, Carmina ecclesiastica—that is, tituli, poems for the dedication of a church or its altar. Among them are very beautiful poems for the dedication of two churches built by him in Malmesbury and for one built for Abbess Bugga, probably his sister.

Sherborne Abbey's close, St. Aldhelm's statue - Digby Memorial, Dorset (kindly provided by the Sherborne Abbey)

Sherborne Abbey's close, St. Aldhelm's statue - Digby Memorial, Dorset (kindly provided by the Sherborne Abbey)

Most interestingly, the saint wrote a collection of 100 Latin riddles (Aenigmata) and handed them over to King Aldfrith. The word “riddle” comes from an old English word meaning “advise” or “explain”. Therefore, a riddle’s role is to teach by representing old things in new ways. The saint’s riddles were extremely popular and didactic through the early middle ages and were copied in many monasteries, thus popularizing this genre. In this collection one sees the wisdom, erudition, power of observation and inquisitive nature of the holy man. It is not for nothing that St. Aldhelm is praised by some as “the first European librarian”.

Below we give three riddles from Aldhelm’s collection (translated from Latin by W. B. Wildman in his book, Life of St Ealdhelm (1905). This selection as well as some other facts used in this article are kindly provided by Sheelagh Wurr from Bishopstrow, the author of a booklet on St. Aldhelm, entitled St. Aldhelm of Wessex, His Life, His Work, and His Miracles):

Forth from the fruitful turf I spring unsown,

My head gleams yellow with its shining flower;

At eve I shut, at sunrise ope again;

Hence the wise Greeks have given my name to me.

(Answer: a sunflower)

Though the war trumpet bray with hollow brass,

The lutes throb sweetly and the bugles call,

My inward parts give forth a hundred notes,

And, when I roar, men hear no other sound.

(Answer: an organ. It was said that St. Aldhelm was the first English saint to make an organ with his own hands!).

Of willow wood and tough bull-hide am I,

And I can stand the shrewdest knocks of war;

With my own frame I guard my warrior’s frame

And shield him from death’s grip. Who like myself

Has felt as oft the deadly blows of war

And known as many wounds, a soldier bold?

(Answer: a shield)

St. Aldhelm’s biographers describe the saint’s pilgrimage to Rome, which was then the spiritual capital of Western Christendom—the holiest place where the apostles preached and countless martyrs laid down their lives for Christ. This pilgrimage took place in 693. Aldhelm was cordially welcomed by Pope Sergius (a Syrian from Antioch), mentioned above, and they served the Liturgy together every day through Aldhelm’s stay. The saint of God returned to England with many gifts, among them were privileges to his monasteries at Malmesbury and Frome (they became independent from their dioceses and subordinate to Rome directly), not to mention relics of saints, holy icons and vestments.

Our saint took part in a number of Church Councils convened by English bishops under St. Theodore and his successor St. Brithwald. Aldhelm’s wisdom and experience were held in such esteem that hierarchs would often ask for his advice in decision-making during Councils. Thus, one such assembly was summoned in about 705 in Wessex. Among the issues considered there were the problems with the Britons living in the Kingdom of Dumnonia (Cornwall and most of Devon) that bordered Aldhelm’s area of mission in Wessex. The local Celtic inhabitants stuck to the old and by that time outdated traditions of calculating Pascha1, though all other Churches of Britain had agreed on following the Roman method. More than that, the Dumnonians regarded Angles and Saxons (their former invaders) as “schismatics”, refusing to pray and even to share meal with them. St. Aldhelm was asked to solve this situation. The saint wrote a letter to King Geraint of Dumnonia in which he explained to him the correct Paschalia, asked them to keep integrity and reproached them for their failure to live in harmony with universal Orthodoxy. Faith without works is dead (Jm. 2:17), the saint concluded. And his efforts brought forth fruit. The Celts little by little abandoned their pride and gave up the wrong Paschalia.

In 705 (or 706 according to another version) the final and most responsible stage in St. Aldhelm’s life commenced. After the death of the holy Bishop Hedda of Wessex his huge diocese was divided into two at a specially-convened Council. The new sees were located in Winchester (the eastern part) and in Sherborne in Dorset (the western part). The learned monk Daniel was elected bishop of Winchester, and St. Aldhelm was unanimously elected bishop of Sherborne. The saint humbly refused but, much against his will, was finally persuaded to assume responsibility for this see, as the Church needed a holy and experienced hierarch like him. This new diocese included Wiltshire, Dorset, Somerset and even the Celtic Devon and Cornwall. Despite his old age (he was sixty-six at the time of his consecration) Aldhelm was the most active and zealous archpastor. He built the first cathedral in Sherborne, founded many new churches in the diocese (among them were those at Bath in Somerset, where St. Aldhelm’s reputed cross still exists, and in Doulting). At the same time, the saint remained Abbot of Malmesbury and two other of the monasteries he founded—at Frome and Bradford-on-Avon. In spite of his age, Aldhelm day and night preached the Word of God, made regular journeys across his diocese (the whole of Southwest England!), devoting time to fasting, prayer and performing acts of charity. Many other monasteries asked his advice, help and spiritual guidance. Among them were Glastonbury and Wimborne.

In spring 709 (according to another version, 710), St. Aldhelm became weak. It was clear that his end was near. He said words of farewell to all his monks, priests and spiritual children among the laity, exhorting them to keep peace, love and unity. Despite his illness the holy bishop continued his pastoral journeys, but death came to him while at Doulting in Somerset. In the final minutes of his life the saint asked his assistants to carry him into the little local church, which he loved and where he used to sit from time to time for a quiet prayer. There was a holy well nearby, by which he liked to recite psalms—and miracles still occur at this place. It was there that on May 25 (according to the old calendar) our saint’s holy soul was taken by God and ascended to the heavenly dwellings. St. Aldhelm was seventy: he had served as Abbot of Malmesbury for thirty-five years and as Bishop of Sherborne for four years. His last will was to be buried in his beloved Malmesbury.

St. Aldhelm's icon at the Digby Chapel of Sherborne Abbey, Dorset (kindly provided by the rector of Sherborne Abbey) Thus ended the earthly life of this holy man, who travelled all over his diocese, instructed monks and priests, built churches, had encyclopedic knowledge, sang both ballads and moving spiritual songs, recited poetry, played the harp, the fiddle and the pipes, was full of warmth and compassion, had a sense of humor, had time for everyone, was a devout Christian, won the trust and friendship of both scholars and peasants, could read the Bible in Hebrew, attracted disciples from as far as Scotland and Gaul, was patient and amicable rather than angry and strict with those erring, seldom slept, ate little, and lived in poverty—a man through whom many residents of Wessex came to Christ.

St. Aldhelm's icon at the Digby Chapel of Sherborne Abbey, Dorset (kindly provided by the rector of Sherborne Abbey) Thus ended the earthly life of this holy man, who travelled all over his diocese, instructed monks and priests, built churches, had encyclopedic knowledge, sang both ballads and moving spiritual songs, recited poetry, played the harp, the fiddle and the pipes, was full of warmth and compassion, had a sense of humor, had time for everyone, was a devout Christian, won the trust and friendship of both scholars and peasants, could read the Bible in Hebrew, attracted disciples from as far as Scotland and Gaul, was patient and amicable rather than angry and strict with those erring, seldom slept, ate little, and lived in poverty—a man through whom many residents of Wessex came to Christ.

According to tradition, St. Egwin, Bishop of Worcester and Abbot of Evesham, who was among Aldhelm’s friends, saw a vision at the moment of St. Aldhelm’s repose. He walked over 70 miles south to Doulting and learned the sad news. Then he ordered that the saint’s body be delivered to Malmesbury. Multitudes of people followed the procession through its route and those who touched the bier were healed of various ailments and consoled for their sorrows. The procession made stops every seven miles for a rest and stone crosses in honor of Aldhelm were erected at each of the stopping sites. These were at Doulting (Wilts), Frome (Som), Westbury (Wilts), Bradford-on-Avon (Wilts), Bath (Som), Colerne (Wilts), Little Drew (Wilts), Malmesbury (Wilts). Those crosses were extant at the time of William of Malmesbury. Some Saxon fragments remain at the church of Frome, parts of the Saxon inscribed crosses - at Littleton Drew, and a large part of the cross at the churchyard of St. John the Baptist’s Church in Colerne.

Aldhelm performed numerous miracles which continued after his death from his relics, holy wells, personal things, and at places associated with him. Let us mention several of his miracles. When workmen were finishing St. Mary’s Church in Malmesbury they roofed it with several beams that were expensive and delivered from a great distance. One of them proved too short. There was no extra beam. The news was reported to Aldhelm. He came and prayed quietly, holding the beam in his hands. When measured again, it turned out to be the right size! The saint concealed his miracle and joked: “Never mind! You probably made a mistake while measuring the first time!” However, in the following centuries Malmesbury Abbey twice burned down in fires entirely, except for this very beam, which rotted from age many years later.

Aldhelm built a small church in Wareham in Dorset before his departure for Rome so that he could stay inside to pray before he left. At the time of William of Malmesbury the walls of this church stood intact, but it was roofless except from one small section above the sanctuary to prevent birds from defiling it. And every time during heavy rain shepherds would gather inside this church and, quite contrary to the laws of nature, no drop ever fell within the walls of this roofless church!

During his stay in Rome, Aldhelm celebrated services every day. There he was given a miraculous chasuble (epitrachelion, or priest’s stole). It was made of fine silk on an Eastern pattern, scarlet, with tracery and images of peacocks. Once, after the service, the saint pulled the chasuble off, thinking that his assistant was standing near him to catch it. But there was no assistant beside him at that moment and the chasuble would have fallen down but for a sunbeam that suddenly struck through the window and had it “suspended” on itself at a distance above the floor! That chasuble was kept at Malmesbury for many centuries and displayed to pilgrims as a relic. Alas, during the destructive Reformation it disappeared, as did the relics of St. Aldhelm.

Among the pope’s presents that Aldhelm received in Rome was an altar slab of white marble, four feet long and three feet wide, with carved crosses along its edge. It was so heavy that a camel carried it as far as the Alps. There that the animal fell exhausted, and the altar slab smashed. The man of God implored God to restore both the camel and the slab, and they were immediately restored. However, the mark of the break remained. At the time of William of Malmesbury this very slab lay at St. Mary’s Church in Bruton, Somerset (originally founded by Aldhelm) as a treasure. According to some information, the altar of the current church of Bruton is wooden and set in the middle is a block of marble with a crack across it. This may or may not be the one brought back by Aldhelm.

After Aldhelm’s consecration as a bishop in Canterbury he heard that some ships from Gaul had moored at Dover. He hurried there to find out if the sailors had something useful for this church. And he found for sale a manuscript that contained the full texts of the Old and the New Testaments. However, the price was too high and the sailors did not want to reduce it. While casting off, the men laughed at Aldhelm because he was unable to buy the book but a few minutes later a strong wind arose in the sea. The sailors were helpless and by signs implored the saint to save them. Aldhelm crossed the sea, and it instantly became calm again. The men sailed back, came ashore and offered Aldhelm the Bible for free, begging pardon. The saint forgave them, but gave them the sum that he had originally offered them for the book. In the twelfth century that unique Bible was still kept at Malmesbury Abbey and shown to pilgrims.

After the repose of Aldhelm his relics were enshrined in the church of the Archangel Michael at Malmesbury where they rested for 200 years. He came to be venerated by all the faithful living in south-western England and several centuries later his memory was celebrated nationwide. In 855 King Ethelwulf of Wessex (795-858), father of Alfred the Great, donated a splendid silver shrine for St. Aldhelm’s relics, adorned with plates of silver gilt whereon the scenes of his miracles were depicted. But the monks decided not to move his relics. In the tenth century King Athelstan (895-939) especially venerated Aldhelm and donated many relics to Malmesbury Monastery. After his death this king was buried in this monastery, and his body is believed to rest somewhere within Malmesbury Abbey Church to this day.

King Athelstan's tomb at Malmesbury Abbey, Wilts (author - Arpingstone)

King Athelstan's tomb at Malmesbury Abbey, Wilts (author - Arpingstone)

On May 5 (according to the old calendar) 986 the saint’s relics were finally translated into the aforementioned silver shrine, and this event has been marked as his second feast-day ever since. However, St. Dunstan of Canterbury, foreseeing that the shrine might be pillaged by the Vikings one day, had his holy body removed to a stone tomb, higher up inside the abbey church. In 1016 the Vikings attempted to attack and plunder Malmesbury Monastery. One of them even ran up to the silver shrine, but as soon as he touched it he was struck blind. In the same minute the whole band of the Vikings, terrified by some invisible force, fled in panic, and, unlike almost all other monasteries of England, Malmesbury was saved. Some years later two abbots after a period of fasting opened the stone tomb where they expected to find Aldhelm’s relics and discovered them absolutely unchanged. They solemnly translated them into the silver shrine.

After the Norman Conquest, the veneration of Aldhelm was questioned and discontinued by Lanfranc (archbishop of Canterbury 1070-1089), but Osmund, bishop of Salisbury (†1099), authorized its resumption with the new translation of his relics in 1078. In addition, Osmund took one of Aldhelm’s left arm bones and enshrined it into an arm-shaped reliquary at Salisbury Cathedral. At that time new miracles followed, including the healing of a girl with a spinal disease, a dumb man, and a blind boy. There was a continual stream to the saint’s relics afterwards, and even guards were hired to keep order during the influx on special days. Unfortunately, the veneration of saints was suppressed during the 1530s Reformation. The veneration of Aldhelm slowly began to resume just over 100 years ago. Today he is again held in great veneration by the Orthodox (with a mission of the Western Rite ROCOR dedicated to him), Catholics and Anglicans. There is a modern Orthodox service to him in English and icons of him are painted. Stained glass windows and statues of St. Aldhelm can be found in many churches and cathedrals in Southwest England. Now let us talk about the holy places associated with him.

Holy places associated with St. Aldhelm

The Saxon Church of St. Laurence in Bradford-on-Avon, Wiltshire (photo by Irina Lapa)

The Saxon Church of St. Laurence in Bradford-on-Avon, Wiltshire (photo by Irina Lapa)

The beautiful and ancient little market town of Bradford-on-Avon (Bradford meaning “broad ford”) stands close to the Wiltshire-Somerset border. It is situated on an elevation in a picturesque setting between the Mendips, the Salisbury Plain and the Cotswold Hills. Bradford’s narrow curving paved streets run up a hill. Its architecture has Dutch features as it was rebuilt by Flemish weavers. Once Bradford boasted 300 mills; today fine Tudor, Jacobean and Georgian houses remind us of its former wealth.

Inside St. Laurence's Saxon Church in Bradford-on-Avon, Wilts (photo by Irina Lapa)

Inside St. Laurence's Saxon Church in Bradford-on-Avon, Wilts (photo by Irina Lapa)

The true gem of Bradford is the tiny Saxon Church of the holy Archdeacon Laurence of Rome, one of the most complete Saxon churches in England, built about 700 by St. Aldhelm. The presence of this saint is strong in this shrine with its mysterious atmosphere. It is a miracle that St. Laurence’s was built in the Orthodox period of English history and has not changed much since then! You will not see Norman or Gothic architecture here—the church is tall, high, with narrow windows, lit only by candlelight inside, and its interior is simple with a homely atmosphere—a typical church of the early Orthodox English. It is built of yellowish stone with thick walls. St. Laurence’s has three small parts: a nave, a chancel and the north portico, or transept. The large south door, numerous arches, windows in the nave south wall, the chancel south wall and the portico west wall are Saxon. One of the surviving Saxon marvels of the church interior is the carved figures of two hovering angels in the east nave wall (part of a more complex sculptural scene). It is believed that the portico was once used as a chapel with an altar. It houses a font and displays the church’s photographs and documents. The altar in the chancel is made of a piece of ancient stone and there are fragments of an early cross on the wall above it. The spirit of warmth and holiness reigns here, and services are held to this day. The nave is twenty-four feet long, thirteen feet wide and twenty-six feet tall.

The altar and cross fragments inside the chapel of St. Laurence's Saxon Church, Bradford-on-Avon, Wilts (photo by Irina Lapa)

The altar and cross fragments inside the chapel of St. Laurence's Saxon Church, Bradford-on-Avon, Wilts (photo by Irina Lapa)

St. Laurence’s was rediscovered not so long ago and “by accident”. In 1001, King Ethelred the Unready (ruled 978-1016) gave the land and church at Bradford to the nuns of Shaftesbury Abbey in Dorset where the relics of St. Edward the Martyr were kept. St. Laurence’s may have kept the relics of St. Edward or even of St. Aldhelm for some time. Thanks to the influence of Shaftesbury, this church has some late Saxon and early Norman elements. Worship continued here for centuries, but in time St. Laurence’s was forgotten and services stopped. For several centuries St. Laurence’s was used for secular needs, namely as a granary, a warehouse, and a mortuary; its nave accommodated a school, and its chancel—a cottage. Since the Saxons used to build tall churches, the church was divided into several floors, and the upper floor became a dwelling. The church was hidden behind the numerous buildings that surrounded it.

It was only in 1857 that Canon William Henry Jones (1817-1885), a historian and vicar of Bradford, discovered that this building was nothing other than a Saxon church. During repair works the priest found the carvings of the Saxon angels in it. He went on with his research and found out that William of Malmesbury had written that “the wonderful ancient Saxon Church still stands in Bradford-on-Avon and is dedicated to St. Laurence”. The building was at once purchased, reconsecrated in honor of St. Laurence, restored over the 1870s, and this real gem of Anglo-Saxon architecture has been open for believers ever since. In addition to this Saxon church, Bradford-on-Avon boasts the fine 900-year-old Holy Trinity Church, which contains one of the longest squints in the country, enabling people to view the priest elevating the Host at the High Altar from the aisle; St. Mary’s Tory, a pilgrim chapel on the top of a hill offering breathtaking views of the surroundings; the Tithe Barn that was built by an abbess of Shaftesbury in the thirteenth century; the rare fourteenth-century chapel on the bridge over the Avon, dedicated to St. Thomas a Becket.

The picturesque market town of Malmesbury stands in the Wiltshire part of the Cotswolds. It is situated on a hill, surrounded by the River Avon and its tributary from three sides. The first church appeared here in the mid-seventh century, and the monastery existed at Malmesbury from 675 till about 1540 without interruption, one of the few continually existing monasteries over such a long period in England. The town of Malmesbury grew around the monastery. Throughout the Middle Ages it was one of the major centers of holiness, prayer, education, and learning in Britain. Apart from St. Aldhelm, King Athelstan and William of Malmesbury, this monastery is associated with Monk Eilmer of Malmesbury—the first European to build a hang glider and make a flight! In about 1010 he fixed wings to his hands and feet, launched himself from the sixty-five-foot-high monastery tower, flew around 660 feet and fell, breaking both legs. Bedridden until his death, Eilmer lived a very long life (he died after the Norman Conquest), wrote astrological treatises,2 and came to the conclusion that his failure was because he had forgotten to provide himself with a tail. Over the centuries scientists retold the story of Eilmer and took inspiration from it.

A stained glass depicting Monk Eilmer at Malmesbury Abbey, Wilts (photo from Wikipedia)

A stained glass depicting Monk Eilmer at Malmesbury Abbey, Wilts (photo from Wikipedia)

The abbey was rebuilt in the twelfth century and for some time its tower was the highest in England. Although Henry VIII closed the monastery in 1539, the substantial part of its church’s nave has been used as an Anglican parish church since then and called “Malmesbury Abbey Church of Sts. Peter and Paul” (the monastery before its closure had been dedicated only to St. Paul for 200 years). Due to a major collapse in the sixteenth century the present church (huge as it is) is over twice as small as the original. The edifice is very beautiful both externally and internally. It is famous for its twelfth-century Biblical scenes on the south porch, notably the figures of six apostles on either side.

Inside, the abbey, among other sights, has a modern chapel dedicated to St. Aldhelm. There is also a set of four stained glass windows depicting its four great sons, namely St. Aldhelm, St. Maeldub, Eilmer and William. Athelstan, who endowed and decorated many churches during his reign and gathered many saints’ relics from abroad, is commemorated in the abbey in a stone monument and a medieval tomb. The abbey also boasts a fifteenth-century illuminated copy of the Bible. A curious feature of the church is the box-like structure at triforium level on the south side of the nave. It was presumably either an observation post or a place of penance. The abbey is still a popular pilgrimage site and welcomes up to 65,000 guests per year, according to its website.

Malmesbury Abbey, Wiltshire (source - Mapio.net)

Malmesbury Abbey, Wiltshire (source - Mapio.net)

There are some abbey ruins and the Abbey House Gardens next to the abbey church, and a separate museum is dedicated to Athelstan. The former monastery’s guesthouse is now used as a hotel named The Old Bell and it claims to be the oldest hotel in the country. Some books of the formerly rich monastic library are now kept at the parvise, a building that originally was part of the abbey. The former monastery brewery survives as well. Malmesbury has a modern Catholic Church of St. Aldhelm. Among numerous medieval wells located at the top of the hill where Malmesbury stands there is one, the oldest well, dedicated to St. Aldhelm. Tradition says that it is the very well in which the saint used to pray through the night to mortify his flesh. The well is now on the grounds of a private house. At times St. Aldhelm’s Flag flies in Malmesbury to celebrate the saint: it is a white cross on a red background - that is, a color-reversed England’s flag of the Great-martyr George.

The whole county of Wiltshire is filled with folklore associated with our saint. In his Natural History of Wiltshire (1969) the author John Aubrey mentions that “Aldhelm, abbot of Malmesbury, riding over the ground at Hazelbury, did throw down his glove, and bade them dig there, and they should find great treasure, meaning the quarry,” implying that the saint discovered Box Ground oolite Bath stone beds whose stone was to be used in the construction of the abbey. The same author mentioned the miraculous St. Aldhelm’s bell that once existed at Malmesbury Monastery, which reputedly drove away thunder and lightning by its tolling. In a more earthly note, among the celebrities associated with Malmesbury is the philosopher-materialist Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679), who was born here and whose ideas are not in tune with the town’s 1400 years of deeply Christian life.

The beautiful little town of Sherborne stands in northwest Dorset on the River Yeo. In addition to its magnificent abbey, the town is proud of its famous castle, medieval and Georgian houses built of ochre-colored stone. Its Saxon name meant “clear stream”. At one time Sherborne was the capital of the Kingdom of Wessex. A diocese was founded here in 705 and produced three holy bishops, namely, St. Aldhelm; St. Wulsin (a disciple of St. Dunstan, a prominent scholar, a man of austere ascetic life; he became Abbot of Westminster in 980 and served as bishop of Sherborne 992-1002, feast: January 8/21. His vestments and bishop’s crozier were kept as special relics); and Alfwold (a humble monk who would always eat from a simple wooden plate; loved and took inspiration from Sts. Cuthbert and Swithin; served as bishop of Sherborne 1045-1058; feast: March 25/April 7). It was St. Wulsin who in 998 founded a monastery at Sherborne which existed until the Reformation, and the former monastic church has been used as an Anglican parish church ever since. In 1075 the Diocese of Sherborne ceased to exist and was transferred to Old Sarum near Salisbury (however, this ancient diocese was revived in 1925 as a Suffragan See of Salisbury). It is also noteworthy that St. Alfred the Great was educated in this town and a school has permanently existed here since the eighth century.

Sherborne Abbey exterior, Dorset (kindly provided by the Rector of Sherborne Abbey)

Sherborne Abbey exterior, Dorset (kindly provided by the Rector of Sherborne Abbey)

Sherborne Abbey in honor of the Mother of God is still a great center of worship, music and a popular pilgrimage site. The edifice retains a mix of various architectural styles of several periods, including some Saxon elements (notably the door at the west end of the north aisle). Architecturally the abbey is famous for its Perpendicular Gothic fan vaulting ceiling in the nave and quire. In addition to its chancel, nave, quire, transepts and aisles, the church has the Lady Chapel and numerous other chapels, old and new. There are two reredoses at the abbey. The numerous beautiful abbey windows depict Christ, the Mother of God, the apostles, the Magi, saints, Biblical events and celebrities. It also houses ten fifteenth-century misericords with carvings—a distinctive feature of pre-Reformation English monasteries and cathedrals. One of the abbey’s towers holds the heaviest set of eight bells in the world.

Interior of Sherborne Abbey, Dorset (photo by Liz Burt, kindly provided by the rector of Sherborne Abbey)

Interior of Sherborne Abbey, Dorset (photo by Liz Burt, kindly provided by the rector of Sherborne Abbey)

The abbey has some unique burials. Although the relics of all its saints were lost during the Reformation, those of Sts. Wulsin, Alfwold and the virgin-martyr Juthware of Cornwall, whose feast is on July 13/26, are all commemorated annually by the abbey. The north choir aisle contains the supposed tombs of the elder brothers of St. Alfred the Great, Kings Ethelbert and Ethelbald; the Wykeham Chapel has the grave of the poet Thomas Wyatt (1503-1542, who translated Petrarch); and in the abbey close there is the Digby Memorial which commemorates George Digby who sponsored much of the abbey’s nineteenth-century renovation (it features several statues, including that of St. Aldhelm). Apart from this statue, the abbey memorials that are significant for Orthodox include St. Juthware (with her head under her arm) window in the quire; St. Aldhelm’s window holding his cathedral’s model at the Lady Chapel by Christopher Webb; another St. Aldhelm’s window in a great gallery of saints in the windows high up in the Quire (by the firm Clayton & Bell); the modern bronze statue of St. Aldhelm by Marzia Colonna by St. Catherine’s Chapel; St. Aldhelm’s statue in fibreglass at the Holy Sepulcher Chapel; another St. Aldhelm’s figure, also by Marzia Colonna, in the niche about the south west porch; St. Aldhelm’s icon in the Digby Chapel (by John Coleman, the abbey’s iconographer in residence); St. Wulsin’s image in the southwest window in the south aisle (information provided by the Rector of Sherborne Abbey). Such is one of the most beautiful churches of England, nicknamed “the Cathedral of Dorset”.

St. Aldhelm's fibreglass at the Holy Sepulcher Chapel inside Sherborne Abbey, Dorset (kindly provided by the Sherborne Abbey)

St. Aldhelm's fibreglass at the Holy Sepulcher Chapel inside Sherborne Abbey, Dorset (kindly provided by the Sherborne Abbey)

The town of Frome (pronounced “froom”) stands at the eastern edge of the Mendip Hills in east Somerset on the River Frome. It once flourished thanks to a wool and cloth industry and at one time eclipsed neighbouring Bath. Later church ornaments and statues were produced here. Earlier, Saxon kings used this wooded area for hunting, but the town grew after the foundation of the monastery by St. Aldhelm in 685. Eadred, King of England between 944 and 955, died in Frome.

Inside St. John the Baptist's Church in Frome, Somerset (photo from Wikipedia)

Inside St. John the Baptist's Church in Frome, Somerset (photo from Wikipedia)

The Church of St. John the Baptist was built on the site of Aldhelm’s monastery between the twelfth and fifteenth centuries. It was renovated in the nineteenth century. This very large and splendid church has a unique feature, namely “Via Crucis” (the Way of the Cross)— seven scenes in sculpture from Christ’s way towards Golgotha, which one sees in Anglican churches very rarely. The edifice has a statue of its founder, St. Aldhelm. Inside, it is richly decorated with statues and stained glass windows, including those of saints.

Crypt of Thomas Ken at St. John the Baptist's Church in Frome, Somerset

Crypt of Thomas Ken at St. John the Baptist's Church in Frome, Somerset

At the east end lies the tomb-crypt of Thomas Ken (1637-1711), a High-Churchman and one of the “fathers of modern English hymnology”, who is commemorated by some Anglicans as a saint on June 8. At one time Ken served as Bishop of Bath and Wells, but following the “Glorious Revolution” he refused to swear allegiance to William of Orange and Mary II, becoming a “non-juror bishop”. Known for his piety, he spent the final years of his life in quiet and contemplation. His hymns, “Awake My Soul”, “Praise God from Whom All Blessings Flow”, “All Praise to Thee, My God, This Night” are sung in Protestant churches. A chantry chapel and a stained glass window are also dedicated to him at St. John’s. Some Saxon fragments are displayed at the east end of its south aisle. They are believed to be parts of the cross erected here in honor of Aldhelm, when his body was being carried from Doulting to Malmesbury.

St. Aldhelm's well in Frome, Somerset (photo by Maigheach-gheal from Geograph.org.uk)

St. Aldhelm's well in Frome, Somerset (photo by Maigheach-gheal from Geograph.org.uk)

However, most pilgrims come to this holy place because of its well. Though the well may date to the time of St. Aldhelm, the present elegant Victorian-era chapel-structure that stretches from the front of the church downhill is less than 200 years old. The well chapel is of decorative rather than of historic value, though it has been decorated every year on Saturday nearest to Aldhelm’s feast in a “well-dressing” ceremony since 1985. The St. Aldhelm’s holy well is on the other side of the churchyard, but it was diverted to flow underground towards the chapel.

The isolated and peaceful village of Doulting lies in the Mendips in Somerset. Aldhelm founded a church here in about 700 and reposed in the same place nine years later. From the eighth century on the village belonged to Glastonbury Monastery. Doulting quarry is famous for its use in the building of Wells Cathedral and parts of Glastonbury Monastery. The village parish church is dedicated to St. Aldhelm and is visited by pilgrims. It dates from the twelfth century onwards. It stands in an idyllic nook. It is notable for having a carving of a green man [often seen in medieval English churches as a human face with branches and foliage growing out of the mouth) and a set of gargoyles [grotesque carved human or animal faces or figures projecting from the gutter of a church, typically acting as a spout to carry water clear of a wall]. The church interior features stained glass windows and plentiful statuary, including a carved figure of St. Aldhelm (seen far on the left on the picture to the article) inside the nave.

Chancel of St. Aldhelm's, Doulting, Somerset (kindly provided by the churchwarden of Doulting)

Chancel of St. Aldhelm's, Doulting, Somerset (kindly provided by the churchwarden of Doulting)

A holy well, originally the source of the River Sheppey, has existed here since St. Aldhelm who used to bathe in it. It has curative properties to this day and some pilgrims come to collect its water even from far afield. It is dedicated to Aldhelm. The well is seen behind the church, appears from a hillside and flows down a narrow channel. Today the stream is shallow and unfit for bathing. A well-structure was built by it in the late nineteenth century. An atmosphere of holiness is still felt in Doulting. The village primary school bears the saint’s name as well.

St. Aldhelm's Church interior, looking west, Bishopstrow, Wilts (kindly provided by the parish of Bishopstrow)

St. Aldhelm's Church interior, looking west, Bishopstrow, Wilts (kindly provided by the parish of Bishopstrow)

The small village of Bishopstrow lies close to the town of Warminster in Wiltshire on the River Wylye. Its church is dedicated to St. Aldhelm. The first church appeared here in the eighth century as a result of St. Aldhelm’s miracle with the staff. It was rebuilt in the Middle Ages and substantially restored in the eighteenth-nineteenth centuries.

St. Aldhelm's window depicting two versions of his miracle at St. Aldhelm's Church in Bishopstrow, Wilts (kindly provided by the parish of Bishopstrow)

St. Aldhelm's window depicting two versions of his miracle at St. Aldhelm's Church in Bishopstrow, Wilts (kindly provided by the parish of Bishopstrow)

The parish commemorates St. Aldhelm, particularly in a stained glass window that depicts two versions of the miracle that led to the foundation of this church. Local people claim that they can still identify the spot in the village where the miraculous tree blossomed after the saint struck his staff in the ground. The villagers saved this unique church from closure in the 1980s. According to the church guide book, when the congregation dwindled the authorities intended to close St. Aldhelm’s for worship, but the villagers set up “The Friends of St. Aldhelm’s” organization which raised enough money for church conservation. In 1981 lightning struck the church tower and damaged the lightning conductor. The workmen had to dig a trench beneath to replace it and remains of the church of the Saxon period were discovered. The fascinating carved oak screen in the chancel is just 100 years old, but it contains intricate little carvings of leaves and animals. There is a touching rhyme that mentions Bishopstrow:

Joseph’s Glastonbury thorn

Flowers afresh each Christmas morn:

And the spruce tree, full of grace,

Brings to mind Saint Boniface:

And the blood-red roses bloom

Round Saint Alban’s martyrs tomb:

But from his staff an ash-tree sprung

While Aldhelm preached and praises sung.

(Susan Oldham, 1987. Used with the kind permission of the parish of Bishopstrow).

Exterior of All Saints' Church in Somerford Keynes, Glos (kindly provided by the church's fabric officer)

Exterior of All Saints' Church in Somerford Keynes, Glos (kindly provided by the church's fabric officer)

The little village of Somerford Keynes (pronounced “Summerford Canes”) lies in Gloucestershire close to the Wiltshire border near the River Thames. In Roman times there was a settlement locally. The earliest mention of the village dates back to 685, when Aldhelm was given land by the King at Somerford Keynes. The local All Saints Church was founded in the 680s, most probably by Aldhelm, and largely rebuilt in the thirteenth century. The first baptisms were performed in the River Thames. It still retains some Saxon elements, notably the Saxon north doorway which recently was opened up and re-glazed. The door came from the seventh century as was proven by the carbon dating of the mortar. There used to be rare late Saxon standing gravestone fragments at this church, dating to King Canute (ruled 1017-1035). These were stolen in 2013 and discovered in 2015 and are now kept at Corinium Museum, Cirencester, Gloucestershire. There are many other items of antiquity at the church—for example, a font dating to 1100.

The Church of Sts. Aldhelm and Edburga in Broadway, Somerset (kindly provided by the church of Broadway)

The Church of Sts. Aldhelm and Edburga in Broadway, Somerset (kindly provided by the church of Broadway)

The village of Broadway lies not far from the town of Ilminster in south Somerset. The thirteenth-century parish church stands a mile from the village in a secluded spot. It is uniquely dedicated to two pre-schism saints, namely Aldhelm and Edburga. There were at least five saints with the name “Edburga” in pre-Norman England. But since the parish commemorates the memory of St. Aldhelm on May 25 (his feast according to the old calendar), and St. Edburga—on June 15, it becomes clear that the co-patron in question is St. Edburga of Winchester3, the youngest child of King Edward the Elder (ruled 899-924), son of Alfred the Great. Edburga was Alfred’s granddaughter and of Wessex descent. When the saint was three, her father showed the child royal jewels and toys and the Gospel book with a chalice and a monastic habit and asked her to choose. The girl, without thinking, chose the latter, and her parents gave her to St. Mary’s Convent in Winchester (called Nunnaminster), where she spent all her life in holiness and humility. It was said that the nun-princess used to wash sisters’ stockings at night in secret. She died in about 960 as a simple nun and countless miracles were recorded at her relics both in Winchester in Hampshire and in Pershore in Worcestershire. Curiously, there is another village with the same name, Broadway, in the Cotswolds part of Worcestershire, which is visited by thousands of tourists every year. This village, too, has an ancient church dedicated to the same saint—Edburga of Winchester!

Preaching cross by the Church of Sts. Aldhelm and Edburga in Broadway, Somerset (kindly provided by the church of Broadway)

Preaching cross by the Church of Sts. Aldhelm and Edburga in Broadway, Somerset (kindly provided by the church of Broadway)

Altar and east window (during flower festival) at the Church of Sts. Aldhelm and Edburga in Broadway, Somerset (kindly provided by the church of Broadway)

Altar and east window (during flower festival) at the Church of Sts. Aldhelm and Edburga in Broadway, Somerset (kindly provided by the church of Broadway)

Back to Somerset: St. Aldhelm and Edburga’s church is cozy and charming. There is a thirteenth-century preaching cross standing in its churchyard as a reminder of the early Christian origin of this site (the first church may have been built by Aldhelm). At least Aldhelm visited this area and preached here as it was part of his diocese. The cross is seven feet tall and has two sculptured figures on it. The chancel and transepts are the earliest parts of the current church. The temple has several wonders inside. For example, as one of its parishioners writes about the church (used with the author’s permission), “the pulpit is made of black oak and is pre-Reformation. It has delicately carved panels, showing the five wounds of our Lord. It was covered in plaster during the sixteenth century for protection. It was rediscovered in 1900 by the then Rector’s wife (Mrs. Sparrow Watson), who removed the plaster with a knife. It must have been colored originally, as traces of red, green and gold paint were found during the restoration.”

St. Aldhelm's Chapel at St. Aldhelm's Head, Dorset (photo from Wikipedia)

St. Aldhelm's Chapel at St. Aldhelm's Head, Dorset (photo from Wikipedia)

Two charming chapels are dedicated to our saint in Dorset, away from any village or town. The first of them stands on the headland called St. Aldhelm’s Head (though it is often mistakenly referred to as “St. Alban’s Head”), rising over 350 feet above the sea level, on the south coast of the Purbeck Peninsula by the sea, with lots of quarries nearby and the nearest parish at Worth Matravers. The chapel is Norman and square in shape. Some researchers suggest that it was originally built as a lighthouse for Corfe Castle which is not far off. The total area of the interior of this charming, picturesque chapel in an idyllic setting is twenty-five square feet. It is made of stone and has a pillar inside. The present structure dates back to the twelfth and thirteenth century. Services stopped here in the 1600s, in the following century it was left derelict and could have turned into ruins but for the timely nineteenth-century restoration. Services at last resumed in 1874.

Interior of St. Aldhelm's Chapel in St. Aldhelm's Head, Dorset

Interior of St. Aldhelm's Chapel in St. Aldhelm's Head, Dorset

Another period of restoration came 100 years later and in recent years a new altar table was consecrated in it. The stone for it was taken from St. Aldhelm’s Quarry nearby [Purbeck limestone is a hard limestone from Purbeck in Dorset, which is polished and used for decorative parts of buildings, fonts, and effigies]. This striking gem stands on the top of dramatic cliffs. The earthworks around the chapel indicate that it was most likely a church or monastery enclosure in ancient times which implies that the chapel originally may have been a part of a cell or a daughter monastery of Sherborne Abbey or some community founded by Aldhelm. Legends associated with the chapel of St. Aldhelm’s Head are plentiful.

For example, it may have appeared in the 1100s after a groom and a bride had drowned in the sea here. The bride’s father decided to erect a memorial chapel in their honor so that their souls be prayed for thenceforth. There is evidence that girls would use it as a “wishing chapel” in the seventeenth century in order to find a suitable husband by throwing a hairpin into the hollow in its pillar, where some ancient graffiti have been found. According to medieval documents, it was once used as a chantry chapel with a priest praying for sailors in it. At one time it was even used by monarchs while hunting in the coastal Dorset—for instance, King John the Lackland frequented it. Finally, a skeleton of a Christian woman was dug up beside the chapel some sixty years ago—the woman was presumably an anchoress. Mysterious as it is, this isolated little shrine is open every day and accessible by a track from a local farm on foot. It still holds services and is visited by pilgrims.

St. Aldhelm's Chapel in Lytchett Heath, Dorset (photo from Wikipedia)

St. Aldhelm's Chapel in Lytchett Heath, Dorset (photo from Wikipedia)

The other chapel is situated in Lytchett Heath—a wooded area near the villages of Lytchett Matravers and Litchett Minster. As was the case with St. Aldhelm’s Head, it is a conservation area. It is a private chapel built in 1898 for Lord Eustace Cecil from the Cecil family that has owned a country house locally. A contemporary stained glass artist installed some beautiful windows with depictions of Aldhelm’s life in the chapel at the start of this century. In their fundamental work, The Buildings of England, the authors John Newman and Nikolaus Pevsner referred to it as to “idiosyncratic”. In 2005, the 1300th anniversary of Aldhelm’s consecration as bishop, the Anglican Diocese of Salisbury organized series of pilgrimages to the sites connected with the saint. A walking pilgrimage was held from Malmesbury Abbey via Bradford-on-Avon and Sherborne to the St. Aldhelm’s Head chapel where it was joined by the then Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams and proceeded to Renscombe Farm. It gathered 1,500 people, according to the BBC.

A pilgrimage for teenagers was organized in the same year from Lytchett Heath to St. Aldhelm’s Head too. Salisbury Cathedral together with the Diocese of Sherborne have initiated a tradition of holding annual pilgrimages to the holy places of Dorset, especially St. Aldhelm’s Head. Salisbury Cathedral, the tallest Gothic cathedral (with its spire 404 feet tall), which is featured in famous paintings by John Constable, has two statues of St. Aldhelm, one in the south quire aisle and the other (modern) in a niche of its great west front. There are numerous statues of saints and other famous people both outside and inside this cathedral, and there are seventy-nine of them on its west front. Among those represented at the west front (besides Aldhelm) are Sts. Patrick, Birinus, Etheldreda, Thomas Ken, Brithwald, Alban, Alphege, Edmund the Martyr.

St. Aldhelm's Church in Belchalwell, Dorset (photo from Wikipedia)

St. Aldhelm's Church in Belchalwell, Dorset (photo from Wikipedia)

Other Church of England parish churches dedicated to Aldhelm are situated in the tiny village of Belchalwell in north Dorset (the nave is of the twelfth century, the rest is the fifteenth century; the village name implies a cold well on a hill slope); in the hamlet of Branksome in Dorset (the church is less than 150 years old); in the Chessels area of Bedminster, the City of Bristol (built in 1906); in Upper Edmonton in London (this modern church has a unique stained glass window depicting five themes associated with the saint, namely juggling balls, Aldhelm the bishop, a manuscript, a harp, and Malmesbury Abbey); in the parish of Radipole in Dorset. In addition, there are Roman Catholic parishes that bear Aldhelm’s name in the Somerset village of Chilcompton (the church is modern and used by the monks of a neighboring abbey); the Sacred Heart and St. Aldhelm’s in Sherborne; in the village of Edgworth in Lancashire, NW England.

We conclude this article with the hymn and prayer to St. Aldhelm that were compiled at the beginning of this century and are annually sung by the parish of Sts. Aldhelm and Edburga in Broadway, Somerset, on his feast-day (with the kind permission of the parish of the church in Broadway):

The St. Aldhelm Hymn

With the saints whose stories stir us

Lord, we gather in Your Name.

Cultures change and years pass quickly.

Yet Your love is still the same:

Through the ages You have called us.

Given a Gospel to proclaim.

Aldhelm, priest and monk of Wessex

Preached the gospel in his day;

Riddles, songs he used his talents;

Voice to sing and harp to play.

May our gospel proclamation

Be adventurous today.

Lord, You call us as disciples.

Pilgrim people all our days.

Let our worship and our witness

Show the wonder of Your ways.

Keep us prayerful, keep us joyful.

Fill our hearts with songs of praise.

Praise to God, Creator, Father,

Praise to Jesus Christ the Son,

Praise the Holy Spirit, working

In the world since time begun.

Sing with Aldhelm, sing God's glory

While unending ages run.

(Author: Rosalind Brown, 2004)

THE ST. ALDHELM PRAYER

God of mission,

You called Aldhelm to sing of Your love; May our hearts dance with joy,

Our lives tell Your story

And our wills be stirred

To walk with Your people on the Way,

Till we come to the feast of Your Kingdom; Through Jesus Christ, our Lord.

Amen.

Holy Hierarch Aldhelm, pray to God for us!