Why does our monastery have such a strange name?

I really love my native Chernoostrovsky-St. Nicholas Monastery, which is located in the ancient city of Maloyaroslavets in the Kaluga Diocese. Many hear the name of our monastery and wonder what does it mean—Chernoostrovsky? What black island is it talking about?!1 The thing is that our monastery is located on the slope of the mountain that in the old days was called Osobnaya2 or Black Ostrog.3

Why? Because in those early years, the entire mountain was covered with a dense forest that was especially dark against the background of white snow in winter and spring. Over time, Chernoostrozhsky turned into Chernoostrovsky. This is where the name of our monastery comes from.

The very beginning

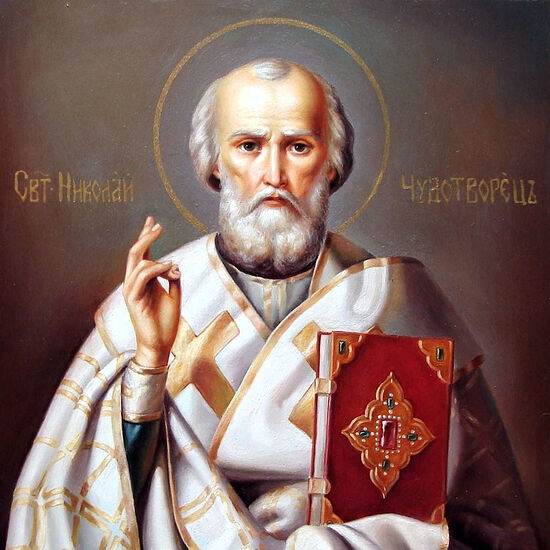

In the old days, these lands belonged to the Obolensky princes. It all started here with a wooden church in honor of St. Nicholas the Wonderworker, and in the sixteenth century, a men’s monastery was built. It was small—five or seven brothers. It was repeatedly burned and impoverished. Since it was wooden, the Churches of the Vladimir Icon of the Mother of God and St. Paraskeva did not survive, but we remember them because the angel of a church remains in place even if the church itself is destroyed. We sing the troparions to the saints of these churches daily.

Chernoostrovsky-St. Nicholas Monastery

Chernoostrovsky-St. Nicholas Monastery

The benefactor of the monastery

In 1776, Chernoostrovsky Monastery was temporarily abolished. Fifteen years later, it was renewed by the initiative of a native of Maloyaroslavets, the Moscow merchant Terenty Elizarovich Tselibeev, who was its main benefactor.

He had a difficult fate. His father died very young at the age of thirty-five, leaving behind a wife and three young sons, of whom Terenty was the middle boy. His father was able to save up a considerable sum before his death, and when the brothers grew up, they all went to Moscow with high hopes for a happy life.

Their hopes were not destined to be fulfilled. The plague came to Moscow in 1771 and Terenty lost both of his brothers. The eldest son’s wife also died from the plague, leaving a new-born daughter Natalia in Terenty’s arms. These deaths of people so close to him were a heavy loss for the young man. Left as the sole heir to a sizeable sum, he no longer sought personal happiness, but devoted himself to the upbringing of his beloved niece and works of charity in his native Maloyaroslavets.

In the late 1780s, Tselibeev married off his grown-up niece, and in 1791, he appealed to the Holy Synod with her about the renewal of the Chernoostrovsky Monastery. He also offered a large monetary contribution for this God-pleasing work.

But the Synod only decided to reopen the monastery ten years later, with the opening of the Kaluga Diocese. From that moment until the end of his life, Terenty spent almost all of his income on the Chernoostrovsky-St. Nicholas Monastery.

Friends

Archimandrite Makary (Fomin) The merchant Tselibeev had a difficult character: He sincerely wanted to help the monks, but couldn’t refrain from attempts to boss around the abbots of the monastery—Hieromonk Methody from Optina Hermitage and then Hieromonk Partheny.

Archimandrite Makary (Fomin) The merchant Tselibeev had a difficult character: He sincerely wanted to help the monks, but couldn’t refrain from attempts to boss around the abbots of the monastery—Hieromonk Methody from Optina Hermitage and then Hieromonk Partheny.

In 1809, Archimandrite Makary (Fomin), who, by the way, also came from merchants, was appointed as abbot of the monastery. He was the first abbot who found an approach to Tselibeev, and they even became friends.

With affection and love, Fr. Makary quickly managed to gain Terenty’s full trust, with obvious benefits for the monastery and without any damage to his abbatial authority. As for Tselibeev, seeing the zeal and business acumen of the new abbot, he immediately encouraged him by donating 2,000 rubles to the monastery, and later even larger sums.

Stone buildings, an underground passage, and delicious fish

Fr. Makary had great love for God and wonderful organizational skills. It was then that stone buildings were first erected in the monastery. An underground passage was even dug out in case of military danger.

The fathers managed the monastery with intelligence and discernment. The monastery ponds had special facilities for storing fish, which was facilitated by the icy flow of the springs—the fish remained fresh even without refrigerators and electricity.

Hardships

During the Patriotic War of 1812, Napoleon and his army of thousands decided to move to Smolensk through Kaluga, to use the supplies from these cities. It was late autumn, and the French were in a hurry to get there before the harsh Russian winter set in.

Serious hardships awaited Maloyaroslavets, and with it the St. Nicholas Monastery.

Cathedral square in Maloyaroslavets, 1812. Alexander Aberyanov

Cathedral square in Maloyaroslavets, 1812. Alexander Aberyanov

Unquestioning faith in the power of God

Having heard about the approaching military operations, the brothers of the monastery began to hide and carry the sacred Church treasures out, sending them to Orel together with the vestments. The abbot, Fr. Makary, blessed for the Icon of the Savior Not Made by Hands to be painted on the Royal Doors. When the iconographer was working, the townspeople walked by and often crossly warned:

“Don’t paint the icon now! The enemy will come and abuse the holy image!”

But Fr. Makary had unquestioning faith in the power of God and firmly replied:

“No, it is the Lord Who will do violence to the enemy.”

The abbot also blessed to write over the icon: Whosoever believeth on him shall not be ashamed.

And indeed, during the most violent fighting on the monastery square, hundreds of bullets flew into the Royal Doors, but not a single one touched the face of the Savior.

In memory of this miracle, Emperor Nicholas I wrote a decree to leave the traces of the bullets and shells in the Royal Doors of the monastery forever, for posterity. In 1830, a memorial plaque with the inscription, “Wounds in memory of the French War,” was placed on the Royal Doors.

A battle near Maloyaroslavets. Oleg Avakimyan

A battle near Maloyaroslavets. Oleg Avakimyan

Royal patrons

Overall, several emperors were involved in the fate of our monastery: Nicholas I, Alexander II and his wife Maria Alexandrovna, and Alexander III and his wife Maria Feodorovna. They were all patrons of the monastery.

Alexander III visited our monastery when he was the tsarevich to learn about the battles that took place here and the details of the glorious victory.

How the mayor burned the bridge right in front of the enemy

The battles were terrible. Napoleon secretly sent two detachments to Maloyaroslavets to capture the defenseless city, where there were no Russian troops at the time. The French intended to prepare apartments for themselves here to stay and rest, for which they had to pass by Ivanov Meadow and cross the bridge over the narrow Luzha River.

Then, at five o’clock in the morning, the French infantry’s shakos appeared from out of the forest and the enemy bayonets of the grenadiers from General Delzons’ division flashed. The French marched with complete confidence in their safety and decisive success.

A contemporary of the events, the Russian memoirist Sergei Nikolaevich Glinka, wrote that before the French,

There spread a level plain of pastures, surrounded by a dense, dark forest, dotted with curly bushes and cut by a light strip of transparent river. The cherry orchards, thatched huts, and an occasional stone house with painted roofs, all scattered over the mountains, reminded the Westerners of happy views of Switzerland, of peaceful villages on the banks of the Rhine, with a quiet family life.

Three ancient stone buildings, churches, one wooden one on the north side of the city, the monastery over a deep moat, a stone road between the cliffs—all of this spoke to the heart about those places where people rush to worship, on pilgrimage, to repent, and to realize in solitude the purpose of their existence, their destination!...

There were no military cliques anywhere on the streets of the city, no formidable weapons, not a single banner calling for protection, waving above the bayonets, crossed the enemies’ field of vision, and all assured Delzons that, passing by Borovsk, he would also take Maloyaroslavets without even the slightest resistance.

But instead of resting, the Russians prepared a surprise for the uninvited guests: The mayor of Maloyaroslavets at that time, P. I. Bykovsky, summoned the people and burned the bridge right in front of the French.

Glinka writes:

And suddenly, through the rotted straw piled under the bridge, from the black smoke of the brushwood, a seven-headed fiery serpent rose into the air, and a blood-red flame engulfed the bridge, forming a crimson tongue, as if teasing the enemy battalions so calmly ready to start across the bridge! The solid piles and joints were burned, the log foundations connecting the two banks collapsed, and the astonished soldiers stopped with exasperation, lowing their guns to their feet and incredulously, some of them silently, others with loud curses, looked around at each other…

Battle of Maloyaroslavets. Alexander Averyanov

Battle of Maloyaroslavets. Alexander Averyanov

How the French nearly drowned in the Luzha

The frustrated French began to build floating bridges, and the pontoon companies began to show the Russians their nimble skill, while the idle French grenadiers strolled along the shore, looking complacently at the city and dreaming of rest and relaxation in the houses there.

But at that time, a resident of Maloyaroslavets, the secretary of the district court, Savva Ivanovich Belyaev, fled from the steep mountain to the mill. The daredevil waved his hand to the townspeople, setting an example, and they quickly destroyed the dam. The water burst out of the solid bulwark with a whoosh, a roar, and foam, tearing it apart with its leaden, bubbling force, overflowed its banks, and spreading over Ivanov Meadow, instantly flooded the entire area.

The enemy was forced to retreat empty-handed. Later, Napoleon, sharing memories of past campaigns, lamented:

“My valiant soldiers crossed many rivers, but this Russian Luzha they couldn’t cross!”

“An angry bear, armed with a hammer”

Discouraged, some of the French soldiers turned and went to spend the night in the village of Grodno, ten miles away, and some settled down for the night right there in the field and lit fires. At that time, the unarmed citizens—women, children, the elderly—rushed to take advantage of the reprieve, to leave the city along the Kaluga road.

The French waited more than a day to be able to make the crossing, and this time proved enough for the Russian troops to arrive in Maloyaroslavets. General Dokhturov’s infantry corps, reinforced by artillery, General Platov’s Cossack units, and General Dorokhov and Seslavin’s detachments arrived in the city.

And then Maloyaroslavets fully corresponded to its coat of arms: “An angry bear, armed with a hammer.” According to an eyewitness, “this symbolic coat of arms contained some longstanding prophecy of an unheard-of terrible defense.”

Bloody battle

On October 24, a bloody battle ensued—so terrible that there were practically no captives. It lasted eighteen hours without a break, with up to 24,000 men involved on both sides.

Around noon, Napoleon himself arrived, personally observing the course of the battle. The city changed hands eight times. The most violent battles unfolded at the walls of our monastery, where the French, having gained a foothold, successfully repelled the attacks of the Russian infantry. Deacon Boniface refused to leave his native monastery and was later found dead.

The exact number of dead was difficult to count; according to various estimates, from six to eight thousand on each side. Among the missing were many who died in the fire. If we consider that Maloyaroslavets was a small provincial town with a population of all of a thousand and a half people, then the number of dead exceeded the number of residents several times over and shocked all the witnesses of the battle.

One of the participants in the battle, the commander of the French battalion, the engineer-captain Eugene Labom, later recalled:

“You could only tell the streets apart by the numerous corpses strewn about them. With every step, there were severed arms, legs, and heads crushed by passing artillery pieces. All that remained of the houses were smoking ruins, under the burning ashes of which charred and dilapidated skeletons could be seen everywhere.”

Only a few houses, about twenty out of more than 200, survived the fire in Maloyaroslavets. The city’s stone churches and the monastery buildings were severely damaged.

How Napoleon’s luck changed

General Alexis Joseph Delzons was one of Napoleon’s favorite commanders. During the fierce battle on the monastery square, Delzons, trying to encourage his soldiers, was mortally wounded by a bullet to the head. His blood brother, who rushed to his aid, was also killed. Their deaths made a very heavy impression on the French and was a turning point in the battle.

Here, at our monastery, Napoleon’s luck changed—from that moment, he began to suffer setbacks.

By the evening of October 24, the French still remained on the ruins of the city, but the Russians took up the defense on the commanding heights surrounding Maloyaroslavets from three sides.

Division General Delzon in the Battle of Maloyaroslavets. Alexander Averyanov

Division General Delzon in the Battle of Maloyaroslavets. Alexander Averyanov

How Napoleon was almost taken prisoner

On the night of October 25, Napoleon and his advisers and aides-de-camp spent the night in the village of Gorodnya near Maloyaroslavets, in an old, rustic hut. A military council was held to decide what to do: to continue to fight their way to Kaluga or retreat?

Marshall Jean-Baptiste Bessières recalled:

“Napoleon spent the first part of the night bent over a map, deep in thought, listening to reports. Everything said that the Russians were preparing for battle the next day, but the French were trying to avoid it; none of the military leaders wanted to go to Kaluga. For such an undertaking, the army, even the guards, did not have enough courage...”

The French slept a little before dawn, then the emperor, accompanied by a small group of staff and aides, went to reconnoiter the Russian position. The two squadrons of his guards that always accompanied him were delayed a little by the impetuous departure of the emperor, and Napoleon had to endure a dangerous adventure, being nearly captured.

Leaving in the pre-dawn twilight and fog, the emperor very quickly found himself coming nearly face to face with the Russian Cossacks, who were conducting reconnaissance and attacked the French artillery depot and baggage trains. To the terror of the staff, together with Napoleon, they suddenly found themselves among the crowd of Russians. The French were saved only by the twilight, the fog, and the element of surprise.

The grenadier of the Imperial Guard, Sergeant Bourgogne wrote:

“When we appeared on the plain, we saw the emperor almost in the thick of the Cossacks, surrounded only by his generals and staff officers. One of them was wounded in a tragic mistake. When our cavalry had just reached the plain, the officers surrounding the emperor drew their sabers to protect him and themselves, as he was among them and could have been taken captive…”

Interestingly, Napoleon maintained his outward composure and continued his reconnaissance, but later, having called for a doctor, he demanded poison, in case of capture. It seems it was the first time the great general was truly afraid.

On October 26, he ordered his troops to retreat. The French went, or rather, ran back along the previously plundered Smolensk road, where, being unprepared for winter and deprived of supplies, they quickly died from hunger and the cold.

Prayer before the wonderworking Kaluga Icon

Napoleon’s retreat was foretold by the apparition of the Mother of God over the village of Tarutino. She appeared to the Russian people and pointed to the road by which the French had come and by which they were retreating.

In honor of this appearance, a fourth celebration of the Kaluga Icon of the Mother of God was established, on the day of the Battle of Maloyaroslavets.

According to tradition, on the eve of this feast, which has become the feast day of the city, the wonderworking Kaluga Icon is brought from Kaluga to our Chernoostrovsky-St. Nicholas Monastery for the night. The sisters pray before the holy icon all night. In the morning, on the feast itself, the icon is taken in procession along the central city streets. The battle on Ivanov Meadow is reenacted in memory of those days.

A wonderworking elder

If you look at our monastery from above, you can see that it was built in the form of a ship. This is helped by the natural shape of the mountain, and the composition of the monastery buildings. And for several centuries now, the captain of our ship has been our beloved St. Nicholas the Wonderworker.

After the battle, a few French prisoners told about how some special elder with a fiery sword in his hands, who was invincible, was fighting in the first ranks of the Russians. In this miraculous elder, the Russians recognized St. Nicholas the Wonderworker—this is described in the chronicle of Archimandrite Leonid (Kavelin).

Oral tradition has also preserved eyewitness accounts of how the French, when they saw the image of St. Nicholas in one of the churches, began to cry out in horror: “This old man drove us out of Maloyaroslavets.”

From Karizha to Paris

Kutuzov attached such great importance to the Battle of Maloyaroslavets that he said:

“The conquest of the world stopped at Maloyaroslavets. The French were drive from Karizha to Paris!”

(Karizha is a small village on the edge of the Ivanov Meadows).

The brothers of the monastery and the townspeople after the battle

It was a terrible sight after the Battle of Maloyaroslavets: burned houses, streets littered with the bodies of the dead. Around the monastery, all the ravines were also filled with piles of bodies, the dying groaning among them.

Having learned of the destruction of the monastery and the fires in the city, Fr. Makary hurried from Kaluga to Maloyaroslavets in bast shoes and a cassock to new labors and podvigs. Returning to the monastery with the brothers, he saw that everything they had built over many years was destroyed. The first thing the monks did was to bury the dead. They managed to rescue several wounded people with their bodies from the ravines.

The monks dug three brothers’ graves. There is now a memorial to the fallen soldiers and commander-in-chief Kutuzov over one of them. The procession goes there on the Day of the City, and a memorial litiya is served.

Three cannon balls and about a hundred bullets were pulled out of the monastery fence. Fr. Makary wanted to leave them as a memento for posterity, but he couldn’t do it, because the townspeople, who were left without a stake and a yard because of their terrible poverty, gathered up everything and somehow sold or exchanged it.

Eyewitnesses later recalled that residents of the city sold 500 pounds of lead bullets, and in the harsh winter they heated the stoves of their hastily-built temporary shelters with rifle stocks.

And in our times, in the 1990s, the first monastic residents who were organizing gardens were still finding a lot of items in the ground that recalled the great battle.

The restoration of the monastery

After the war, the monks found themselves in difficult conditions, but they didn’t lose heart. The abbot didn’t give up either—he took up the construction of the monastery anew. He went to raise funds, and with his fervent faith, he received what he asked. Influential people learned about the brothers’ situation and the monastery began to gradually revive.

The main benefactor, Terenty Elizarovich Tselibeev, departed to the Lord in 1814 at the age of seventy-four, bequeathing to his beloved monastery all his property (securities, land, garden, house), worth a total sum of more than 70,000 rubles.4

Then the abbot decided to build a stone cathedral in honor of St. Nicholas the Wonderworker, which would become a monument to the war of 1812 and would be unlike other monastic churches.

Until his blessed repose

The cathedral was built, although Fr. Makary didn’t manage to paint it—he died in the arms of a novice in 1839. He was so active that even death found him laboring.

Archimandrite Makary was buried together with his friend and associate, the merchant Tselibeev, in an unknown place in the Cathedral of St. Nicholas.

A new abbot for Chernoostrovsky Monastery

In place of Fr. Makary, the spiritually experienced elder Fr. Anthony from Optina (Alexander Ivanovich Putilov in the world) was sent. From his youth he was brought up in severe asceticism, and his spiritual father was his own brother, Elder Moses.

Interestingly, the third Putilov brother was also a monk and man of prayer, and after the death of their father, his three sons wrote on their father’s monument erected by them at the altar of the Church of All Saints: “The Putilov children: Moses, abbot of Optina Hermitage, Isaiah, abbot of Sarov Hermitage, Anthony, abbot of the Maloyaroslavets-St. Nicholas Monastery.”

The life of the future Elder Anthony was constantly exposed to numerous deadly dangers, but God’s providence preserved him unharmed. In 1812, as a seventeen-year-old boy, he was captured by the French and after ten days of suffering and abuse, he miraculously escaped.

At twenty-one, he headed for the Roslavl forests to his older brother, the hermit Fr. Moses, and would later say: “When I went to stay with my brother, I stayed with him for twenty-four years.”

In 1821, with the blessing of Bishop Philaret of Kaluga (later the Metropolitan of Kiev), both brothers moved from the Roslavl forests to Optina. After the appointment of Fr. Moses as the abbot of Optina, Fr. Anthony was appointed head of the skete and hoped to live his entire life under the spiritual guidance of the beloved elder in the skete—in this corner of Paradise, where he was surrounded by love on all sides.

But the Lord had prepared the abbatial cross for him, and in 1839, the new bishop of Kaluga, Nikolai, knowing the bright life and spiritual experience of the head of the Optina skete, blessed him to go to Maloyaroslavets.

This appointment became a severe trial for Fr. Anthony.

Serious illness

Three years before his transfer to Maloyaroslavets, thanks to his exhausting monastic labors and many hours of prayerful podvigs, Fr. Anthony developed a severe leg disease that caused him terrible suffering until his repose. His legs were covered in wounds up to his knees and sometimes bled profusely. The elder’s secret monastic podvig was to bear this cross of a serious and prolong ailment throughout his entire life.

The elder also joked about his illnesses. Ivan Vasilievich Kireevsky once said to him: “Here, Batiushka, the word of Scripture, that many are the afflictions of the righteous, is coming true with you. What a heavy cross the Lord has laid on you!” “It happens,” the elder replied, “that the righteous have afflictions, and I am full of wounds, as the holy prophet David says: Many wounds shall be to the wicked.

Obedience from the Lord

After Optina, the monastery here seemed like a noisy capital to Fr. Anthony—it’s not located in some dense forest, like the Optina skete, but right in the middle of the city noise. Additionally, the inner, spiritual life of the monks left much to be desired, and Fr. Anthony was sent here to establish the true rules of a monastic residence.

Perhaps the former abbot, exhausted from great labors, could no longer manage the monks by the end of his life, and, after his repose, the brothers were left without any guidance at all for three months, and apparently began to weaken from despondency.

Fr Anthony wrote about it in a letter:

“… After the death of my predecessor, anarchy continued for three months, and what supplies there were, all were exhausted or exchanged for vodka, for, being deprived of a good shepherd, there was nothing to console oneself with, and if the anarchy had continued, God knows what would have happened.”

He also wrote:

“And the feast of the Nativity of Christ was met with such joy that all the sheep, without telling the shepherd, dispersed throughout the city to honor, or, to put it more directly, to dishonor Christ, so that there was no one on the kliros to say ‘Lord have mercy,’ so the next day I locked all the monastery gates so my sheep couldn’t go to their former pasture.

“I spent the first three months alone with unspeakable sadness and looked at everything with tearful eyes, so that my chest began to ache from frequent sighs, and I lost both sleep and appetite; but out of his love and mercy, Father Abbot [Moses] sent me a dozen very trustworthy people from his brotherhood, and with them, with the help of God, for your holy prayers, I am now beginning to introduce a desert coenobitic order in the monastery…”

Fr. Anthony also recalled his experiences as follows:

“One day I strongly felt my spirit overwhelmed within me, and dozing off, I saw in a subtle dream the face of the fathers, and one of them, apparently the primate, blessing me, said: ‘You were in Paradise; you know it, but now labor, pray, and don’t be lazy!’ And suddenly, having woken up, I felt a certain calm within myself. Lord! Grant me a good end!”

Often during his abbacy, Fr. Anthony would complain to his elder and brother about the heavy burden that was so hard for him to bear, to which Elder Moses would sternly reply:

“You must bear your abbacy without murmuring, as an obedience from the Lord.”

A lesson from the elder

There is a well-known story of a monk who was accustomed to oversleeping in the morning. St. Anthony urged him to reform, but he pleaded poor health. The elder himself went to Matins, despite the fact that he couldn’t stand due to the illness in his legs.

After Matins, he went to this brother’s cell and, getting down on his knees, began to ask him to spare him, so infirm, and to start going to church himself from then on. There was blood accumulating in his boots from his wounds, pouring out onto the floor. The monk was struck by the podvig of the elder, who took care for his salvation even in such illness, and began to labor zealously in asceticism.

The saint’s labors

St. Anthony led the Chernoostrovsky Monastery for fourteen years. Despite his serious illness, he was forced to go to Moscow himself to collect donations for the monastery. By the elder’s efforts, the Transfiguration Church was consecrated, and in 1843, St. Nicholas Cathedral was finished and consecrated, becoming also a monument to the heroes of the Patriotic War of 1812.

In 1845, St. Anthony was awarded the golden pectoral cross for his work for the benefit of the monastery. He enjoyed the love and respect of St. Philaret (Drozdov), the Metropolitan of Moscow, who often invited him to concelebrate.

The sick elder repeatedly asked to be released into retirement, but this request was fulfilled only in 1853, by the intercession of St. Philaret, and the elder returned to his home skete at the Optina Hermitage.

St. Anthony now rests in the Kazan Cathedral at Optina next to his beloved brother and spiritual father, St. Moses. In 1996, both were canonized as locally-venerated saints in the Synaxis of Optina Elders. They were glorified for Churchwide veneration by the Council of Bishops of the Russian Orthodox Church in 2000.

A naval officer and a monk

After St. Anthony, Archimandrite Nikodim (Nikolai Petrovich Demoutier in the world) (1799-1864) became the abbot of the monastery. He came from hereditary nobles of the St. Petersburg Governorate. In his youth he studied in the Naval Cadet Corps, then served as a naval officer in the Black Sea Fleet and rose to the rank of captain.

Nikolai Petrovich preferred the monastic path to a military career and, exchanging his officer’s uniform for a cassock, he became a novice at the Ploschanskaya Theotokos Hermitage at the age of thirty-four. There he met the future Optina Elder Makary (Ivanov), whom he loved from the heart, as an experienced spiritual guide.

But a year later, Fr. Makary moved to the Optina Hermitage, and Nikolai Petrovich—to the Holy Trinity-St. Sergius Hermitage near St. Petersburg, where the abbot was Archimandrite Ignatius (Brianchaninov).

Optina Elders Anthony, Moses, and Makary

Optina Elders Anthony, Moses, and Makary

Spiritual growth

After a while, Nikolai Petrovich began to long for Elder Makary’s spiritual guidance and asked the abbot to be transferred to the Optina skete, where he arrived in 1836.

For four long years the former naval officer labored as a simple novice at Optina, and then began his new life in the monastic rank—the worldly Nikolai Petrovich was no more, but Monk Nikodim was born. He was tonsured into monasticism at Optina in 1940, and two years later he was ordained as a hierodeacon, and then as a hieromonk.

Abbot of the Meschovsky and Chernoostrovsky Monasteries

Almost immediately after his ordination, Hieromonk Nikodim was appointed by His Grace Bishop Nikolai as abbot of the Meschovsky-St. George Monastery. Within a few years, the new abbot brought the monastery into a better state than before, both externally and internally. Under him, the number of monks nearly doubled, from seventeen to thirty. For his great labors, Fr. Nikodim was elevated to the rank of igumen.

At that time, his Optina spiritual friend, Elder Anthony, was heading our Chernoostrovky Monastery and had long asked to retire to the Optina skete because of his sickness. When he was finally released, Fr. Nikodim was appointed abbot of Chernoostrovsky Monastery, which he led from 1853 to 1862. Igumen Nikodim was elevated to the rank of archimandrite at our monastery and received the Order of St. Anna, 3rd class.

Not as a superior, but as an elder brother

In the life of Archimandrite Nikodim, it is said that in relation to his brother he “behaved not as a superior, but as an elder brother; to his hierarch as an obedient son; to the elders, experienced in the spiritual life, and especially to the great elder Fr. Makary, as a submissive and devotes disciple…”

The life also says about Fr. Nikodim that even as the the abbot of the large monastery, he “often swept the dust from his cell himself… always set up the samovar himself, set up and cleaned the dishes for tea himself, and often went about in a tanned sheepskin oat and in bast shoes. In the midst of managing the monastery, he often thought about the solitary life…”

For the repose of departed soldiers

In 1859, a landowner of Maloyaroslavets County, the retired Major Theodore Maximovich Maximov, appealed to Fr. Nikodim. He talked about how he himself participated in the battle of 1812 in Maloyaroslavets, was wounded, and witnessed the heroic death of may his war buddies. The retired major suggested that a stone chapel in honor of the holy Great Martyr George the Victorious be erected next to their resting place, and that a warm cell be built at the chapel for monks who would read the Unceasing Psalter for the repose of the fallen soldiers.

The chapel was built and consecrated, and Major Maximov made a monetary contribution to the construction. Archimandrite Nikodim established the tradition of annually, on the day of the battle, making a procession from the monastery and all the city churches to this chapel for a panikhida for the slain soldiers.

Blessed repose

Archimandrite Paphnuty (Osmolovsky) There is information that Fr. Nikodim was going to be appointed the abbot of the Optina Hermitage, but he greatly desired to labor in the solitary life, and besides, his health, already far from herculean, began to deteriorate greatly.

Archimandrite Paphnuty (Osmolovsky) There is information that Fr. Nikodim was going to be appointed the abbot of the Optina Hermitage, but he greatly desired to labor in the solitary life, and besides, his health, already far from herculean, began to deteriorate greatly.

In 1862, two years before his death, by his own request, Archimandrite Nikodim was released into retirement in our monastery. He secluded himself for prayer and spiritual reading, leaving his cell only for the services.

A few days before his repose, the new abbot, Igumen Paphnuty, tonsured him into the schema with the name Nikolai. Before his death, Schema-Archimandrite Nikolai communed several times; the last time was two hours before his blessed repose.

Abbot Paphnuty

After Fr. Nikodim, the abbot was Hieromonk Paphnuty (Peter Martinovich Bonch-Osmolovsky in the world). He was a native of the city of Glukhov in the Chernigov Governorate and belonged to the ancient and noble Bonch-Osmolovsky family, from which came many generals, colonels, medical doctors, and other famous people of the Russian Empire.

Peter Martinovich entered Optina as a young man, labored in asceticism there for more than a quarter of a century, acquired many spiritual gifts during this time, and was appointed the confessor of Optina and the head of the skete. According to contemporaries, Fr. Paphnuty was a strict ascetic.

After his appointment as the new abbot of Chernoostrovsky-St. Nicholas Monastery, he was elevated to the rank of igumen and led the monastery for nearly thirty years, from 1862 to 1891. He is buried under the altar of the Church of All Saints.

The flourishing of the monastery

Thanks to the efforts of the abbot and the brethren, the monastery flourished in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century: Monastic prayer was constantly offered here, there was a parochial school, a water supply system, a pilgrim’s hotel, a greenhouse, a pond with fish gardens, and a small brick factory.

After the revolution

In 1918, the monastery was closed. The local Emergency Commission made several searches, as a result of which all the monastery’s property was confiscated. The last abbot of the monastery, Archimandrite Ilia, by order of the authorities, made an inventory of the monastery’s property that showed that the monastery possessed a rich archive and library. Their fate is currently unknown.

St. Nicholas Cathedral remained active for another eight years, until 1926, and then it was also closed. At various points, a museum, pedagogical and library science technical schools, a chess club, general education and art schools, a bread factory, and construction organizations operated in the monastery. Gradually, the monastery fell into complete desolation. Besides the churches, only one building was preserved, where an art school was located.

Chernoostrovsky-St. Nicholas Monastery, 1992

Chernoostrovsky-St. Nicholas Monastery, 1992

The rebirth of the monastery

In 1991, the monastery was returned to the Church, and from that time begins a new history of our beloved monastery.