A new project of the Spiritual-Educational Center of Sretensky Monastery on the study of Sacred Scripture, conducted by the well-known catechist Sergei Komarov, has begun. We will be discussing the book that begins the liturgical collection of the Apostolic epistles—the Acts of the Holy Apostles.

The Church is an organism that breathes the Holy Spirit

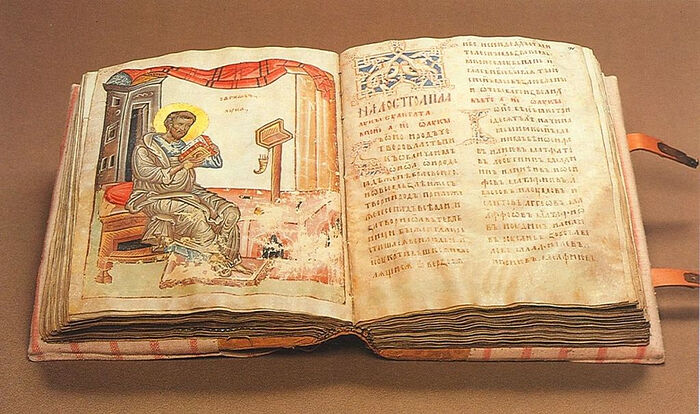

The Apostol1 occupies a special place in the New Testament cycle of books. The New Testament presents its own law-giving books—the four Gospels,2 teaching books—the Apostolic epistles, a prophetic book—the Apocalypse, and Acts, the only historical book.

As a text, the New Testament begins with the Apostol. The first written texts of the New Testament were the epistles of the Apostle Paul. Presumably, the first New Testament book was written in 42 AD—the First Epistle to the Thessalonians. Then came the Gospels and other epistles. The Apostle Paul was the first to understand that it was necessary to record the Apostolic understanding of the faith, because the Apostles would depart, but Christianity will remain.

Although in this Epistle to the Thessalonians, St. Paul himself expressed the opinion that the Second Coming of Christ would occur during his lifetime and that of the generation contemporary to him: We which are alive and remain unto the coming of the Lord shall not prevent them which are asleep (1 Thess. 4:15).

Then commentators had to justify this point: Was St. Paul really mistaken? But note that the Church hasn’t removed these passages from the Bible. The fact is that acute eschatological expectations are “sewn” into the Church’s consciousness. Christians should always be ready for the Coming of Christ; they should wait for Him, although we’re not given to know the time and date. And this isn’t a panic-stricken expectation with some kind of animal fear, but a desire to see the Lord: Even so, come, Lord Jesus (Rev. 22:20).

We pray every day in the Lord’s Prayer: “Thy Kingdom come.” We call for Christ to come and reign in His Kingdom. But this is our paradoxical Christian life—we seem to love Christ, but we fear His Second Coming. We desire to be with the Lord, but our sins convict us, and we fear this encounter.

***

The book of Acts wasn’t written before all the Apostolic epistles, but it stands as first in the series, because it unites the four Gospels and the history of the Church. Acts talks about how the Church was born. It provides the background for all of the Apostolic epistles.

This is something very important, by the way—one Biblical book stands as the background for others. For example, to understand the Psalter, you have to read the books of the Old Testament—the Books of Kings, Exodus—then the historical canvas of the Psalter becomes clearer. And the book of Acts is a kind of background for the Apostolic epistles.

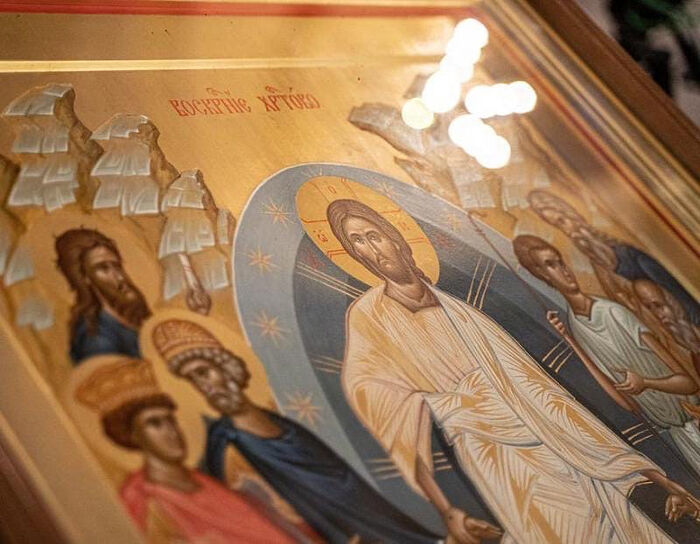

St. John Chrysostom said that this book can benefit us no less than the Gospels. It’s interesting that we read it in the brightest and most joyful period of our liturgical life—from Pascha until Pentecost. Why?

***

With Pascha begins the liturgical movement towards Pentecost, and Pentecost is the conceptual center of the book of Acts. All the central events of the book come from this center or point towards it. And we pass through our liturgical journey from Pascha to Pentecost with the book of Acts in hand. It is our guide, a kind of tuning fork for our thoughts and feelings in this period.

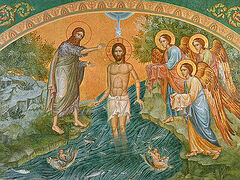

We move from Pascha to Pentecost, the day of the descent of the Holy Spirit upon the Apostles, and the book of Acts tells us much about the Holy Spirit. The term “Holy Spirit” is mentioned in it 56 times. Acts show that the Church is an organism that breathes the Holy Spirit. The Church is born when the Holy Spirit descends upon the Apostles and the entire first Christian community, and the further existence of the Church is life in and with the Spirit.

Sometimes you hear the idea that the Holy Spirit only descended upon the Apostles, but that’s not true. Our commentators write that the Spirit descended on the entire community, that is, the fullness of the grace of the Holy Spirit is given to the entire Church. The Church is the guardian of all the gifts of the Spirit, the receptacle of the Spirit, the place of the life of the Holy Spirit.

Pentecost, which we’re headed towards, is the birthday of the Church, and the book of Acts is the story of the first years of the life of the Church, of the beginning of its existence. Reading Acts for the birthday of the Church, we move with thoughts about the Church; we learn to understand the life of the Church, immersing ourselves (through reading) into the everyday life of the first Christians.

St. John Chrysostom says we read Acts immediately after Pascha because you can see there the fulfillment of the prophecies that Christ proclaims in the Gospel:

Christ said to His Disciples: He that believeth on Me, the works that I do shall he do also; and greater works than these shall he do (Jn. 14:12), and foretold to them that they shall be brought before governors and kings, and that they will be beaten “in the courts and their synagogues” (cf. Mt. 10:17-18); that they will be subjected to the cruelest torments and will triumph over everything; and that this Gospel of the Kingdom shall be preached in all the world (Mt. 24:14). All of this, and much more, that He said to His disciples appears to be fulfilled in this book with all accuracy.

We can say that the main character of Acts is the evangelical preaching. Every page of this book is about the propagation of the Gospel. Acts ends with the Apostle Paul going to Rome, and it’s very symbolic. The main Apostle winds up in the main city of the world. The Gospel (in the person of the Apostle) has come to Rome—that means it will sound forth throughout the earth. And indeed, during the life of the Apostles, the Good News was preached throughout the civilized world, throughout the Roman Empire.

The book of Acts speaks about the life of the first Christians soon after the Resurrection of Christ and immerses us into a joyful post-Paschal mood. Reading it, we feel the breath of the life of the ancient Church; we feel like participants in the existence of the Apostolic Christian community.

The Apostle Luke

The author of the book of Acts is St. Luke, of the Seventy Apostles. He doesn’t name himself, but the Church indicates his authorship.

Luke isn’t a Hebrew name. Most likely it’s from the Roman Lucillius. Church historians believe that St. Luke was born in Antioch, was a pagan, and then accepted Jewish circumcision (thereby becoming a proselyte), and later heard the preaching of the Apostles and came to believe in Christ.

But there’s also another opinion. The “Prayer for Travelers” says: “Luke and Cleopas traveled with the Savior to Emmaus.” Where is this episode taken from? From the Gospel of Luke. Two travelers walk to Emmaus from Jerusalem and meet Christ along the way. The name of one is given—Cleopas, but the name of the second is not, but, since it’s the Apostle Luke writing, it’s believed that he is speaking about himself, and this idea is also included in Church Tradition. But there’s a discrepancy here—how could someone with a Roman name be a disciple of Christ during Christ’s lifetime, considering that Christ didn’t preach to foreigners? Therefore, the first version is probably closer to the truth.3

St. Luke wrote the book of Acts in Rome in 63-64 AD, according to Blessed Jerome of Stridon. He writes to the venerable Theophilus (1:1), whose name means “lover of God.” We don’t know if this was a real person or a collective image. Perhaps St. Luke is writing to all Christians, and everyone who reads this book is a lover of God. Or perhaps there was a non-random concurrence of a real person and his name, which turned out to be a common name.

Acts is an historical work and St. Luke is a real historian. The book of Acts is a bit like the “Biographies” of Plutarch. St. Luke is well aware of ancient literature and builds his narrative according to all the laws of historical books of his time. We see a huge number of facts, names, and locations. Obviously, the Apostle felt that there would come a time when people would doubt whether the Gospel story really happened. That’s why St. Luke carefully records such details.

The author of Acts uses an interesting method of historiography. He mainly talks about two Apostles: St. Peter (until the twelfth chapter), and from the twelfth to twenty-seventh—St. Paul. Talking about Sts. Peter and Paul, St. Luke tell us the whole history of the ancient Church. He moves not from an event to a person, but from a person to an event; through a person to an epoch.

St. Luke is the best writer in the New Testament. He has the richest Greek language, with a masterful command of the literary word. This is evident even in translations. He adapts to the mentality of Gentiles, using terminology characteristic of them. St. Luke focuses on the universality of the evangelical preaching. It’s important for him that all people absorb the Gospel, not only the Jews. This concerns both the Gospel of Luke and the book of Acts.

Difficulties of the first Christians

The Apostle Luke describes the difficulties facing the ancient Church.

The first is the misunderstanding and rejection of Christianity by the Jews. The confrontation ended with a complete break between Judaism and Christianity. This happened after 70 AD, when the Temple was destroyed. Before that, there was such a phenomenon as Judeo-Christianity.

For example, St. James, the brother of the Lord, was a Judeo-Christian. He observed the Jewish Law, and at the same time was the first Christian bishop of Jerusalem. The entire Christian community of Jerusalem consisted of Jews who observed the Law. We can’t imagine this now—Christians were circumcised, kept the Sabbath, and observed all the Jewish rites. But this is how Christians lived at first.

The second problem was the moral vices of members of the Christian community and discord among the faithful. In the fifth chapter we read about Ananias and Sapphira, who sold their estate and concealed its price. The human passions immediately began to penetrate into the first Christian community, and the Apostles, as pastors, were troubled about this.

The third problem was the procedure for receiving Gentiles into the Church. Today, anyone can come to the Church, repent, and be baptized. But at that time the Jerusalem community was Judeo-Christian, and the question arose about what to do when a Gentile comes to the Church. Does he first have to be circumcised and start keeping all the commandments of Moses and then be led into the Church?

It was later decided at the Apostolic Council to receive everyone into the Church without fulfilling the Law. Only four basic principles were laid down. The golden rule of morality is to not to do others anything you don’t wish for yourself. Don’t fornicate—because fornication was part of the pagan cults, and the Church tried to separate Christians from the pagan mysteries and sacrifices forever. Don’t eat food offered to idols—this is a kind of liturgical watershed between the world of paganism and Christianity. And don’t eat blood. Such restrictions for Gentiles coming into the Church were meant to serve for peace between them and the Judeo-Christians.

The fourth problem was the Gentiles’ resistance to the Gospel preaching. The book of Acts talks about the catechization of the first Gentile Christians. When the Apostles saw that crowds of Gentiles were coming to the Church, they realized it wasn’t enough just to baptize them, but that they needed to change their mentality—they had to be taught. It was easier with the Jews—the conceptual mosaic unfolded very quickly for them. They’d been waiting for the Messiah for a long time, and the Apostles had only to explain that the Messiah is Jesus Christ. But for the Gentiles they had to explain who the Messiah is, why He died and resurrected, why all of this was necessary, and how to believe in Him correctly. That is, there was a lot of work to be done with them.

A large part of the epistles of the Apostle Paul are dedicated to working with people who are already believers. They don’t contain arguments about “why it’s necessary to believe,” but explain how to believe correctly. In fact, all of the Apostle Paul’s epistles have a catechetical function. And the book of Acts is also like this to a great degree.