His Holiness Patriarch Kirill before the miracle-working Vladimir icon of the Mother of God, in the Church of St. Nicolas in Tolmachi. Photo: Pravoslavie.ru.

His Holiness Patriarch Kirill before the miracle-working Vladimir icon of the Mother of God, in the Church of St. Nicolas in Tolmachi. Photo: Pravoslavie.ru.

“You can’t imagine,” one priest I know said, his eyes sparkling, “you just can’t imagine! It turns out—she’s in a church! I myself didn’t even know it. I thought she was in a museum, but she’s in a church! And there’s no one there! No one! You can stand there all day if you want! You can venerate her, make prostrations, stand, sit, I don’t know… You can lie down! I prayed there, I even dozed off on the bench. Do you understand?! She, Herself!

Well “there”, it so happens, is the Church of St. Nicholas in Tolmachi at the Tretyakov Art Museum, and “she” is, as you probably figured out, is the Vladimir icon of the Mother of God. That is, the very one that all of Moscow went out to meet in 1395, seized with terror at Tamerlane’s advance, and not closing the doors of their churches for days.

“And the whole city came out to meet her, the little to the great; and there wasn’t a single person who didn’t weep. Everywhere was heard the prayerful hymns: ‘O our Intercessor, do not give us over into the hands of the Tatars!..’ And the Mother of God heard the cries of the Russian people,” wrote Archbishop Nikon (Rozhdestvensky). Inexplicably to atheist history, the great Tamerlane, frightened by the appearance of the Mother of God, turned away from the city that he was just about to enter and went to lacerate the Kipchak horde, which was at enmity with Moscow. And the icon remained in Moscow.

And today, not a copy but the very icon that had been taken out of the Dormition Cathedral in the Kremlin after the revolution and imprisoned in a museum, has since 1999 been located in the Church of St. Nicholas in Tolmachi, which was returned to the Church in 1993 with the status of the church of the Tretyakov Museum.

On a clear February day, I headed there steaming from the frost, through the Moscow lanes.

***

The Church of St. Nicholas in Tolmachi. Photo: Mikhail Chuprinin / Sobori.ru Like a dreadnaught raising its gangplank at a Moscow pier, the foam of days beating at its bow, the white church of St. Nicholas in Tolmachi has one side on Tolmachi Lane, and the other on the territory of the Tretyakov Museum, and doesn’t let you in on either side.

The Church of St. Nicholas in Tolmachi. Photo: Mikhail Chuprinin / Sobori.ru Like a dreadnaught raising its gangplank at a Moscow pier, the foam of days beating at its bow, the white church of St. Nicholas in Tolmachi has one side on Tolmachi Lane, and the other on the territory of the Tretyakov Museum, and doesn’t let you in on either side.

The doors were closed, and an arrow with the words, “Entrance this way”, pointed to an entrance—also closed—that didn’t seem to be connected with the church, (as it turns out, it is connected to an underground passageway). Behind the glass of the entranceway, glaring in the winter sun, a lady could be seen with epaulets, who in answer to my querying shoulder-raising waved her hand as if to say, yes, you’re going in the right direction, through the gallery entrance.

At the gates is a small, twisting stream of people trying to get in: ruddy-faced foreigners in warm, seemingly children’s pointed caps and thin overcoats, and ruddy-faced Moscow schoolchildren yearning for beauty under the leadership of their class guides.

Inside is a reverent hum. An old-Moscow lady in the cloak room (when I get ready to leave, she would sigh as if dismayed at the departure of her dear guest) unhurriedly takes my fur jacket.

I look around; the signs call to the left: “Entrance to the museum church”. Up the stairs, to the left, my inner compass is thrown off, but the outer one is true. On the transverse, my long-lost policewoman floats by.

A turn, a staircase, yet another cloak room, and a sign on a white door: “Brothers and sisters, entering the church in outerwear is not blessed” (it’s a good thing I’ve already checked my coat!), a board with announcements (the schedule of services plus a homey request to someone to return a book to the library, as if it weren’t the center of Moscow in a church attached to the Tretyakov Museum but somewhere in a quaint and quiet provincial parish). At the candle desk (it is not blessed to light candles, but just to place them on the candlestand—they’ll be lit during services), I thought for a moment and then purchased an Akathist in a slightly rough ocher-colored cover, and a candle. I climb the stairs and…

It is quiet in the empty church, and the sunlight tumbles in bundles onto the floor. It’s really true, there’s almost no one there—only a museum worker keeps order while sitting on a chair, and by the Kazan icon (the church is filled with ancient icons) the tour guide whispers something to two attentive ladies. In the background is barely heard the low rumble of the museum’s temperature regulating device.

I glide towards the royal doors. There, on the left, in a carved wooden case, is… She.

The miracle-working Vladimir icon of the Most Pure Mother of God

The miracle-working Vladimir icon of the Most Pure Mother of God

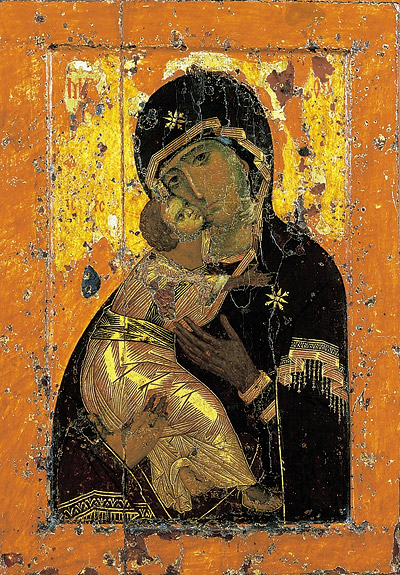

Golden like the gold of autumn, like the most picturesque September forest, the Vladimir Mother of God gazes from her case with such pain as no copy can, copies that now seem like slightly faded portraits; but she is, well, Herself.

I take the Akathist out of my purse and stand by the right cliros, so as not to get in anyone’s way.

Just outside the window, birds are screeching deafeningly. These are Moscow sparrows in the fiercest cold, ringing in with undoubting clarity the spring that’s soon to come.