We continue the story about the elderly nuns of St. Alexei Convent, for whom an almshouse was established in the monastery.

First tonsure in the almshouse

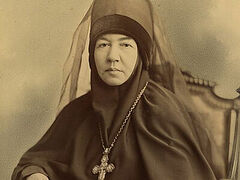

Mother Anna (Scherbakova) Mother Anna (Scherbakova) moved into the monastery’s old folks’ home in November 2000. She hadn’t been tonsured yet, but she became the first nun to receive the tonsure in the home’s Church of Tsarevich Alexei.

Mother Anna (Scherbakova) Mother Anna (Scherbakova) moved into the monastery’s old folks’ home in November 2000. She hadn’t been tonsured yet, but she became the first nun to receive the tonsure in the home’s Church of Tsarevich Alexei.

Mother Anna was, as they say now, an icon of her age. She remembered all of our Primates: Their Holinesses Patriarch Tikhon (Belavin), Sergius (Stragorodsky), Alexei I (Simansky), Pimen (Izvekov), and Alexei II (Ridiger). As a little girl, she went to the funeral of Patriarch St. Tikhon with her father. She recalled that when they went up to bid farewell and give the last kiss, her father picked her up, and little Anya kissed the hand of His Holiness Patriarch Tikhon. For the rest of her life, she remembered how his hands were warm and soft, like a living person. Having received, we might say, a blessing from the reposed St. Tikhon, Anna carried faith and fidelity to the Savior to the end of her days.

And her life passed in the terrible times of fierce theomachy. Anna Akimovna Scherbakova was born on the eve of the revolution in 1916. Of the pious Scherbakov family, she was the youngest daughter. All that is known about her parents is that their names were, like the parents of the Virgin Mary, Joachim and Anna, and that her father was an industrialist before the revolution (Most likely, he owned a factory, because Anna Akimovna once gave one of the residents an old tablecloth that she said was made at her father’s factory).

After the fateful 1917, all the Scherbakovs’ property was taken away, and the family was left in complete poverty. Her father took these catastrophic changes in their fate very hard, and soon went to his grave. Both Annas, mother and daughter, having lost his care, wound up on the street. The children lived in such unbearably strained conditions that they couldn’t help their mother and younger sister. They were taken in by their nanny Tatiana, who once faithfully served the family. She had a tiny room in a communal apartment—all of twenty feet for three people, but they spent many years together in love and harmony. Little Anna slept on a chest, and you could say, grew up on it. It was only after the war that the mother and daughter were given their own room in a communal apartment.

In these terrible years, the Annas’ spiritual father, the famous Protopresbyter Nikolai Kolchitsky, was like their guardian angel. He was the rector of Moscow’s Patriarchal Theophany Cathedral in Yelokhov (since December 27, 1924), where he served until his repose. He was also the chancellor of the Moscow Patriarchate (1941–1960) and was a close assistant to two Patriarchs: Sergius and Alexei I.

Protopresbyter Nikolai Kolchitsky Fr. Nikolai became like a father for Anna Scherbakova. In all the sorrowful and joyful moments of her life, she went to see him and his matushka Varvara. She often visited their home as a dear friend. By the way, there are still spiritual children of Fr. Nikolai living in Moscow today, who remember him as a reverent cleric, an outstanding preacher, and a caring father for his flock.

Protopresbyter Nikolai Kolchitsky Fr. Nikolai became like a father for Anna Scherbakova. In all the sorrowful and joyful moments of her life, she went to see him and his matushka Varvara. She often visited their home as a dear friend. By the way, there are still spiritual children of Fr. Nikolai living in Moscow today, who remember him as a reverent cleric, an outstanding preacher, and a caring father for his flock.

His repose was a great loss for Mother Anna. His funeral was held at the Theophany Cathedral where he had served for thirty-seven years, served by Patriarch Alexei I and a host of clerics and faithful. The church was overflowing. Patriarch Alexei spoke about the departed priest as an outstanding Church figure who had labored greatly in the field of Christ, and called upon his flock to pray for the repose of his soul. Mother Anna prayed for him her whole life and kept his very bright and joyful memory.

Archimandrite John (Krestiankin) became another spiritual mentor for Anna. She met him when he was serving in Moscow in the Church of the Nativity of Christ in Izmailovo. Anna’s mother died at that time. Her funeral was served in church, but there was no one to serve a litiya at her grave. At the Vvedensky Cemetery, where all her relatives had been buried, and now her mother too, Anna suddenly saw a priest coming her way—it was Fr. John (Krestiankin). He served the litiya for Anna’s newly reposed mother, Anna, and after this encounter, the younger Anna started going to the Church of the Nativity of Christ to hear Batiushka preach. And after the death of Fr. Nikolai, she started going to Archimandrite John for spiritual advice until the end of her life. From Fr. John, Anna received a blessing for monasticism and a full monastic habit. But out of her humility she didn’t dare take the veil and so waited nearly twenty years for the particular will of God.

It should be added here that Anna Akimovna worked under Patriarch Pimen when he was still just a regular bishop. She faithfully served God for many years, working for the Church as an accountant, first in the Church of the Holy Protection of the Mother of God in Lyschikov, and then as the head accountant for the Moscow Diocesan administration, under Vladyka Pimen until he became the Patriarch.

While she was young and able, Anna visited monasteries, especially the Pskov Caves where Fr. John (Krestiankin) labored after the war, and the Pukhtitsa Convent, where she was led in the spiritual life by the famous eldress Blessed Mother Ekaterina. Thus Mother Anna’s life was spent in labors and prayers.

In the fall of 2000, Anna Akimovna moved to live in the home at All Saints Church. Her tonsure occurred in an unusual way. At the home, they knew that Archimandrite John had once told Anna: “Anna, I’ll die first, and you’ll depart to the Lord soon after me.” And then he became so sick that they didn’t even hope for him to get better. Anna still wasn’t tonsured, but she remembered the Elder’s promise. They immediately started preparing the necessary documents in the Patriarchate; her habit was already ready—there remained only to perform the tonsure, but who would do it? With the blessing of Fr. Artemy Vladimirov, they went to Donskoy Monastery to Archimandrite Daniel (Sarichev). His cell attendant opened the door, and Fr. Daniel himself met them. He was already very weak and said: “How can I go? I have the obedience not to leave my cell. One eye’s closed and the other already sees quite poorly.” What could they do?... His cell attendant suddenly said, “Anyways, getting tonsured isn’t just tying a headscarf.” So they left with no resolution.

Nun-Martyr Anna (Makandina) But literally the next day, Igumen Mitrophan came to see Fr. Artemy, and he brought a positive resolution to her petition to be tonsured, agreeing to tonsure her himself. “Mother, are you able to walk?” “Yes.” “Then let’s go to the church. It will be more solemn there.” Before her tonsure, Anna Akimovna always worried and asked: “But what will they name me? I really want to stay Anna; I really love my name.” And I remember we told her: “No one knows what they’re going to name you.” “Yes, yes,” Mother Anna responded, “I have to humble myself.”

Nun-Martyr Anna (Makandina) But literally the next day, Igumen Mitrophan came to see Fr. Artemy, and he brought a positive resolution to her petition to be tonsured, agreeing to tonsure her himself. “Mother, are you able to walk?” “Yes.” “Then let’s go to the church. It will be more solemn there.” Before her tonsure, Anna Akimovna always worried and asked: “But what will they name me? I really want to stay Anna; I really love my name.” And I remember we told her: “No one knows what they’re going to name you.” “Yes, yes,” Mother Anna responded, “I have to humble myself.”

The priest started reading the first prayers, then suddenly turned to those present: “Does anyone have a Church calendar?” While people were looking, Igumen Mitrophan took note of the icon lying on the analogion: “What saint is that?” We answered: “The newly glorified Martyr Anna of Krasnoe Selo.” Then we found a calendar and the igumen said: “I don’t need it anymore.” And then we heard (oh, the miracle!) how he named Anna Akimovna Nun Anna in honor of the Nun-Martyr Anna of Krasnoe Selo! That’s how it all worked out—the first tonsure after the glorification and after the turbulent godless years was performed in honor of the novice of St. Alexei Monastery, the New Martyr Anna (Makandina), in her monastery, in her honor.

The tonsure was performed on October 4, 2002. After that, Archimandrite John (Krestiankin) and Mother Anna lived for about four more years. They departed to the Lord in 2006: Fr. John on February 5 in Pskov Caves Monastery, and Mother Anna on March 20 in the Tsarevich Alexei Home. We should add that Archimandrite Daniel (Sarichev) followed after them, on September 8. Memory eternal to them.

“Blessed are they that hear the word of God, and keep it”

Mother Seraphima, Ksenia Alexeevna Rozova in the world, was one of the oldest inhabitants of the Krasnoe Selo home. She was exactly a century old, having been born in Moscow in 1901, and departing to the Lord in 2001.

“The religious worldview was the solid foundation” for the pious Rozov family. The father had a good voice and sang in the church choir. One day, Patriarch Tikhon heard him sing and called on him to give up all his affairs and devote himself to the service of the Church, after which Alexei Rozov became a deacon, and then a protodeacon in the Annunciation Church on Berezhki in Moscow. Ksenia’s brother also received a spiritual education and she herself had deep faith in God and preserved her faith to the end of her life.

Mother Seraphima had two callings from her childhood: medicine and literature. As she herself wrote in her small autobiography, “There’s a connection between my medical and literary inclinations. I think it’s because for both a doctor and writer, the central focus is man. And a correct understanding of man can only come from a holistic examination, including spiritual, physical, and material aspects.”

Medicine turned out to be the stronger calling. But since Ksenia was the daughter of a clergyman, that is, of a “socially unsuitable element,” she was prevented from taking the medical institute entrance exams for twelve years. During this time, Ksenia graduated from the four-year Paramedic-Obstetric School of G. L. Roginsky with the highest grades. After her final exams, at the solemn assembly, the gifted young graduate Ksenia Rozova was noticed by one official guest who said, “This graduate of yours should be given a recommendation for the medical institute.” Ksenia was quite happy, but her joy proved to be premature. There was a Komsomol member who graduated from the technical school with her. When she found out about this recommendation, she reported that Ksenia’s father serves in the Church, so they wrote the recommendation for her instead. When she found out about this, Ksenia wept bitterly, but being a believer, she understood that it was God’s will. In 1925, she started working as a nurse at the Central Transport Hospital, on the Yauza platform of the Yaroslavl Railroad. She worked there for seven years, where she learned much as a young specialist.

Church of the Annunciation of the Most Holy Theotokos on Berezhki. Photo: N. A. Naidenova In 1927, Ksenia enrolled in the Higher State Literary Courses, where she studied for two years, mastering the reading method of the noted Pushkin scholar M. A. Tsyalkovsky. This discipline helped her greatly later in life. In 1932, Kenia was refused entrance to the institute for the twelfth time, and she fell into complete despair. Then a psychologist friend advised her to change her profession, and Ksenia went to work in a library. Her soul calmed down, and Ksenia again wanted to at least find out how medical students are taught. As Mother Seraphima writes in her memoirs: “I told this to the priest at the Annunciation Church on Berezhki where I was a parishioner, helped the priest, wore an apostolnik,1 and carried out obediences, reading and singing on the kliros as a novice on the path to secret monasticism. The rector of the church told me: ‘What could be easier? A member of our parish council (he said her name) got a job at the Medical Institute’s clinic. Tell her I said to give you a job.’ She offered me a choice of several vacant positions. One of them was at the Moscow Institute of Tumor Treatment with a surgical clinic, and that’s where I went.”

Church of the Annunciation of the Most Holy Theotokos on Berezhki. Photo: N. A. Naidenova In 1927, Ksenia enrolled in the Higher State Literary Courses, where she studied for two years, mastering the reading method of the noted Pushkin scholar M. A. Tsyalkovsky. This discipline helped her greatly later in life. In 1932, Kenia was refused entrance to the institute for the twelfth time, and she fell into complete despair. Then a psychologist friend advised her to change her profession, and Ksenia went to work in a library. Her soul calmed down, and Ksenia again wanted to at least find out how medical students are taught. As Mother Seraphima writes in her memoirs: “I told this to the priest at the Annunciation Church on Berezhki where I was a parishioner, helped the priest, wore an apostolnik,1 and carried out obediences, reading and singing on the kliros as a novice on the path to secret monasticism. The rector of the church told me: ‘What could be easier? A member of our parish council (he said her name) got a job at the Medical Institute’s clinic. Tell her I said to give you a job.’ She offered me a choice of several vacant positions. One of them was at the Moscow Institute of Tumor Treatment with a surgical clinic, and that’s where I went.”

The Institute’s administration itself invited Ksenia to take evening classes there. She easily passed the entrance exam, and at the age of thirty-one, Ksenia finally entered the school. In her studies, especially when compiling a history of diseases, Tsyavlovsky’s reading method always helped her. Her teachers considered her history of diseases to be a dissertation. In 1938, Ksenia graduated from the First Moscow Medical Institute and became a graduate student in the Medical History Department. It was the only such department in the country at that time, and Ksenia turned out to be its first graduate student. At her thesis defense, they told her it was practically good enough to be a doctoral dissertation. They advised Ksenia to extend one chapter, after which she could defend it as a doctoral paper, but this wasn’t meant to be—World War II broke out.

Ksenia was offered a job at the State Medical Literature Publishing House, where she worked for fourteen years. There, while working with various authors, she had the opportunity to fully apply the method of book reading she had learned. Mother Seraphima was the editor of the famous work of St. Luke (Voino-Yasnetsky) of Simferopol, Purulent Surgery.

Many authors wanted to work with such a professional editor. However, Ksenia, a deeply religious woman who always went to church, turned out to be undesirable for such a job, and she was fired. At the advice of her spiritual father, she joined the Publishing Council of the Moscow Patriarchate. At that time, the first edition of the Bible published in the Soviet years was being prepared; it was released in 1956.

Although the authorities officially suspended Ksenia Alexeevna from her work, they then loaded her up with unofficial work, as there were no professionals equal to her.

Mother Seraphima (Rozova) When the time came for the publication of various books by the Russian Orthodox Church, Mother Seraphima was asked to prepare a draft for an Orthodox Church calendar in 1993. She was ninety-two then. Seven of her annual Orthodox calendars were published, the last being the calendar for 2001.

Mother Seraphima (Rozova) When the time came for the publication of various books by the Russian Orthodox Church, Mother Seraphima was asked to prepare a draft for an Orthodox Church calendar in 1993. She was ninety-two then. Seven of her annual Orthodox calendars were published, the last being the calendar for 2001.

And in 2001, Mother Seraphima departed to the Lord. She was buried at St. Alexei Monastery, on the territory of the Church of All Saints, on the place where the famous St. Alexei Cemetery once was.

***

In the twenty-first century, it seems that a new St. Alexei Monastery began to gather first in the Kingdom of Heaven. These nuns, who had gone the way of all mortals, some who had sealed their faith with martyrdom at the beginning of the twentieth century, and others, the residents of the almshouse at its very end, prayed to God for the opening of the monastery. Their prayers reached God’s throne, and the monastery, tempered like gold in a furnace, has been revived.