The Feast of the Meeting of Christ in the Temple (February 2) is a feast of the elderly. When the Holy Family entered the Temple courts to offer the required sacrifice for the purification of Mary after her giving birth to Jesus, her Son was recognized as the Messiah by only two people, picked out by the power and illumination of the Spirit from all the multitudes of people swarming through the holy courts, and these two were very elderly. Christ was practically a newborn (little over forty days old) and His Mother was young herself, probably about fourteen years old. But the two people who identified them as the Messiah and His Mother were themselves “well stricken with age” (as the phrase has it), so that fresh-faced youth collided with the wrinkled faces of the elderly.

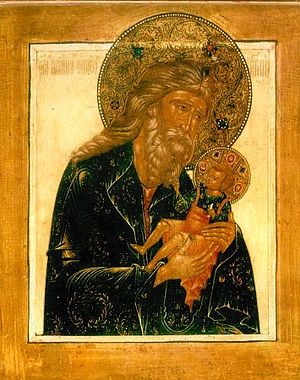

The first wrinkled face belonged to Simeon. God had promised him that he would not die before he saw the Messiah, and he lived in that luminous hope. Every day he rose up from his bed wondering if today would be the day, and every night he retired a disappointed man. Year succeeded year and still he went to his bed with the promise unfulfilled. Then one day, led by the Spirit, he entered the Temple and God pointed out among the hundreds thronging those sacred courts a young woman accompanied by a much older man, and in her arms, a young baby: that child was the Messiah. Boldly he approached them and took the child into his aged arms, praying, “Lord, now You are dismissing Your servant”—a declaration, not a prayer; the Greek verb is in the present tense—and he knew that this child was the sign that he God was dismissing him and he could now die in peace. His eyes had beheld the Messiah, He who was to enlighten all the nations of the world and glorify the people of Israel. Simeon’s age is not given, but he was clearly elderly, for he was now ready to die a happy man. (Traditions which make him one of the translators of the Greek Septuagint offer poetic symbolism and not sober history, for that would make Simeon about 250 years old.)

The other person to recognize the babe in arms as the Messiah was also elderly. Anna was a prophetess—not someone who stood and publically proclaimed oracles like Isaiah did, but a woman to whom God confided things and who stood deep in His secret counsels. St. Luke reported that after her marriage she lived with her husband for seven years, making her about twenty-one or so when she suddenly became a widow. Instead of remarrying she remained in that state, taking her grief into the presence of God and remaining in the Temple day and night—not literally day and night, for there is no reason to think that the Jewish Temple offered dormitories for women—but virtually day and night. She was the first one to enter the Temple when its gates opened and the last one to leave, and she spent all her time fasting, praying, worshipping, and pouring out her heart to the Lord. The Greek text of Luke 2:37 says she was “a widow of eighty-four years”, which could mean that she was eighty-four when she met the Holy Family or that she remained a widow for eighty-four years, which would make her about 105 when she met the Holy Family. Either way, she was a very, very old woman.

God thus chose as the vehicles for His revelation two people who had walked with Him for many years, and who had served Him for decades. He could have chosen anyone, including younger people, people with strength, vigour, and the ability to cross land and sea with the important news. He didn’t. Instead He chose two people who were wrinkled, white-haired (or balding), stiff and bent with age, people who had grown old in His service, people who were soon to die. What does this mean? It means that faithful service is important, and that God honours age. It means that our own goal should be to grow similarly old in the service of God, so that God can confide in us as He did to Simeon and Anna.

Our own culture does not value age. Age is shameful, and the elderly are often shunted off, disappearing into nursing homes, their presence an unwanted burden, their witness and voice of no account. Our culture instead values youth, and we are often treated to the sight of young celebrity twenty-somethings being interviewed on television and consulted about their views on everything from politics to spirituality. When I see such young wrinkle-free celebrities sitting on talk shows and pontificating I often want to shout at the television, “Why are you asking them? They are scarcely old enough to legally vote, drink, or drive, and you think they have some secret wisdom to impart? Their grandparents have forgotten more than they themselves know! Why aren’t you asking their grandparents?” Alas, the experience of the elderly, accumulated often through suffering, too often counts for nothing. They have committed the ultimate offense: they are old, wrinkled, and not pretty. Not even Botox could disguise their shame.

Saner societies than ours take a different view. The Scriptures counsel us to “rise up before the hoary head and honour the face of an old man” (Leviticus 19:32)—i.e. to stand up when a person old enough to have white hair enters the room. Significantly the commandment is rooted in basic respect not just for the elderly, but for God, for the verse ends with the words, “and you shall fear your God; I am the Lord”. Indeed, many if not most societies demand respect for the elderly. Even our own canonical tradition insists upon a certain maturity for its office-holders: deacons may not be ordained until they reach twenty-five years; presbyters until they reach thirty years, and bishops until they reach thirty-five. And in those days, thirty years of age was older than it is now, for a man thirty years old had been married for a while and you could tell how his children were turning out. It is otherwise now; thirty is the new twenty. The point is the Church valued maturity, and made it an essential requirement for those in its service.

Simeon and Anna thus counsel us to flee from the inanity of our culture which despises age and idolizes youth, and return again to a place which respects the wisdom which only the passing of years can bestow. There are exceptions, of course. Some old people remain foolish and stupid, and some young people are replete with a wisdom beyond their years. But these exceptions prove the rule. The Feast of the Meeting brings to our attention God’s choice of the elderly as His vehicles for divine insight. Let us aspire to follow in their footsteps, and grow old in the service and wisdom of God.